For several years, Democracy Fund has been pushing for greater platform transparency and working to protect against the harms of digital voter suppression, surveillance advertising, coronavirus misinformation, and harassment online. But the stakes for this work have never been higher.

One in five Americans rely primarily on social media for their political news and information, according to the Pew Research Center. This means a small handful of companies have enormous control over what a broad swath of America sees, reads, and hears. Now that the coronavirus has moved even more of our lives online companies like Facebook, Google, and Twitter have more influence than ever before. Yet, we know remarkably little about how these social media platforms operate.

With dozens of academic researchers working to uncover these elusive answers, it is essential that we fund and support their work despite Facebook’s repeated attempts to block academic research on their platform.

Earlier this month Facebook abruptly shut down the accounts of a group of New York University researchers from Cybersecurity for Democracy, whose Ad Observer browser extension has done pathbreaking work tracking political ads and the spread of misinformation on the social media company’s platform.

In full support of Cybersecurity for Democracy, Democracy Fund today joined with its NetGain Partnership colleagues to release this open letter in support of our grantee, Cybersecurity for Democracy, and the community of independent researchers who study the impacts of social media in our democracy.

The Backstory

For the past three years, a team of researchers at NYU’s Center for Cybersecurity has been studying Facebook’s advertising practices. Last year, the team, led by Laura Edelson and Damon McCoy, deployed a browser extension called Ad Observer that allows users to voluntarily share information with the researchers about ads that Facebook shows them. The opt-in browser extension uses data that has been volunteered by Facebook users and analyzes it in an effort to better understand the 2020 election and other subjects in the public interest. The research has brought to light systemic gaps in the Facebook Ad Library API, identified misinformation in political ads, and improved our understanding of Facebook’s amplification of divisive partisan campaigns.

Earlier this month, Facebook abruptly shut down Edelson’s and McCoy’s accounts, as well as the account of a lead engineer on the project. This action by Facebook also cut off access to more than two dozen other researchers and journalists who relied on Ad Observer data for their research and reporting, including timely work on COVID-19 and vaccine misinformation.

As my colleague Paul Waters shared in a deep dive blog on this topic:

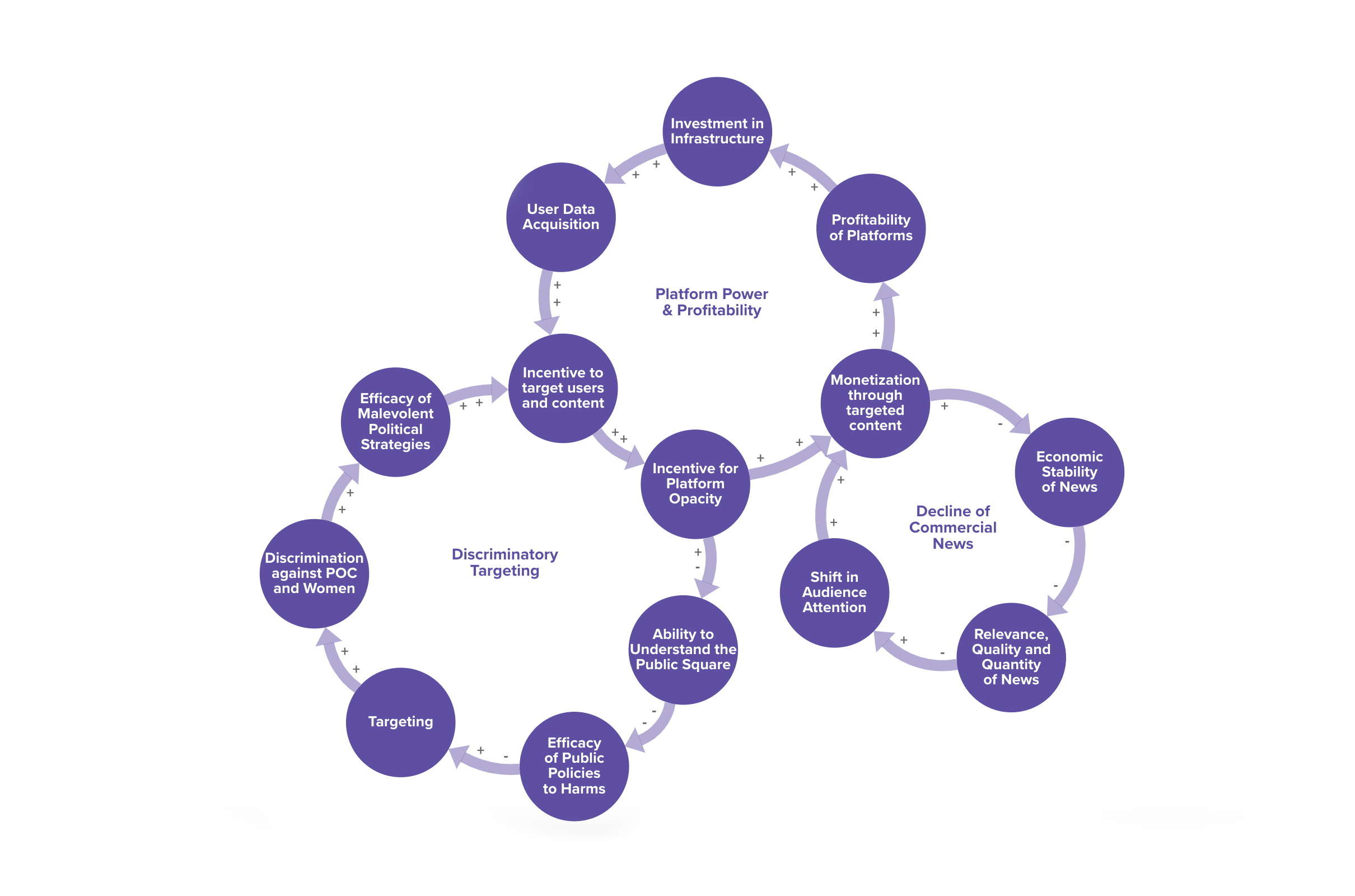

“Platforms have strong incentives to remain opaque to public scrutiny. Platforms profit from running ads — some of which are deeply offensive — and by keeping their algorithms secret and hiding data on where ads run they avoid accountability — circumventing advertiser complaints, user protests, and congressional inquiries. Without reliable information on how these massive platforms operate and how their technologies function, there can be no real accountability. When complaints are raised, the companies frequently deny or make changes behind the scenes. Even when platforms admit something has gone wrong, they claim to fix problems without explaining how, which makes it impossible to verify the effectiveness of the “fix.” Moreover, these fixes are often just small changes that only paper over fundamental problems, while leaving the larger structural flaws intact. This trend has been particularly harmful for BIPOC who already face significant barriers to participation in the public square.”

This latest action by Facebook undermines the independent, public-interest research and journalism that is crucial for the health of our democracy. Research on platform and algorithmic transparency, such as the work led by Cybersecurity for Democracy, is necessary to develop evidence-based policy that is vital to a healthy democracy.

A Call to Action

Collective action is required to address Facebook’s repeated attempts to curtail journalism and independent, academic research into their business and advertising practices. Along with our NetGain partners, we have called for three immediate remedies:

- We ask Facebook to reinstate the accounts of the NYU researchers as a matter of urgency. Researchers and journalists who conduct research that is ethical, protects privacy, and is in the public interest should not face suspension from Facebook or any other platform.

- We call on Facebook to amend its terms of service within the next three months, following up on an August 2018 call to establish a safe harbor for research that is ethical, protects privacy and is in the public interest.

- We urge government and industry leaders to ensure access to platform data for researchers and journalists working in the public interest.

The foundations who make up the NetGain Partnership share a vision for an open, secure, and equitable internet space where free expression, economic opportunity, knowledge exchange, and civic engagement can thrive. This attempt to impede the efforts of independent researchers is a call for us all to protect that vision, for the good of our communities, and the good of our democracy.