In early 2024, Democracy Fund launched the successful All by April campaign, urging funders to make nonpartisan election-related grants by the end of April. We did this to respond to elections and voting nonprofits who have long said that election-year grants arrive too little, too late. The campaign mobilized at least $155 million in election-related support, with nearly 200 signers joining us. Participants pledged to make earlier 501(c)(3) nonpartisan election-related grants, and often in higher amounts. Many also committed to simplifying grant processes, and encouraged others to do the same.

When we surveyed participating funders in late 2024, we found meaningful shifts in philanthropic practices. This year, to build on our understanding of the campaign’s impact, we worked with the Center for Effective Philanthropy to survey 251 elections and voting nonprofits who received philanthropic funding in 2024. While the survey included some organizations who had directly engaged with the All by April campaign, our goal was to capture a broad picture of how the nonprofit sector experienced funding during the 2024 election cycle.

The survey results show that All by April had a strong impact. We learned that many nonprofits received higher levels of funding in early 2024, and experienced more streamlined grant processes and more flexible funding than in prior years.

However, the survey also identified serious challenges in the field, including funding shortfalls and the need for even earlier funds. The overall message we’re taking away: keep your foot on the gas. It’s working, but philanthropy must push harder and do more.

Here’s a deeper dive into some of the things we learned:

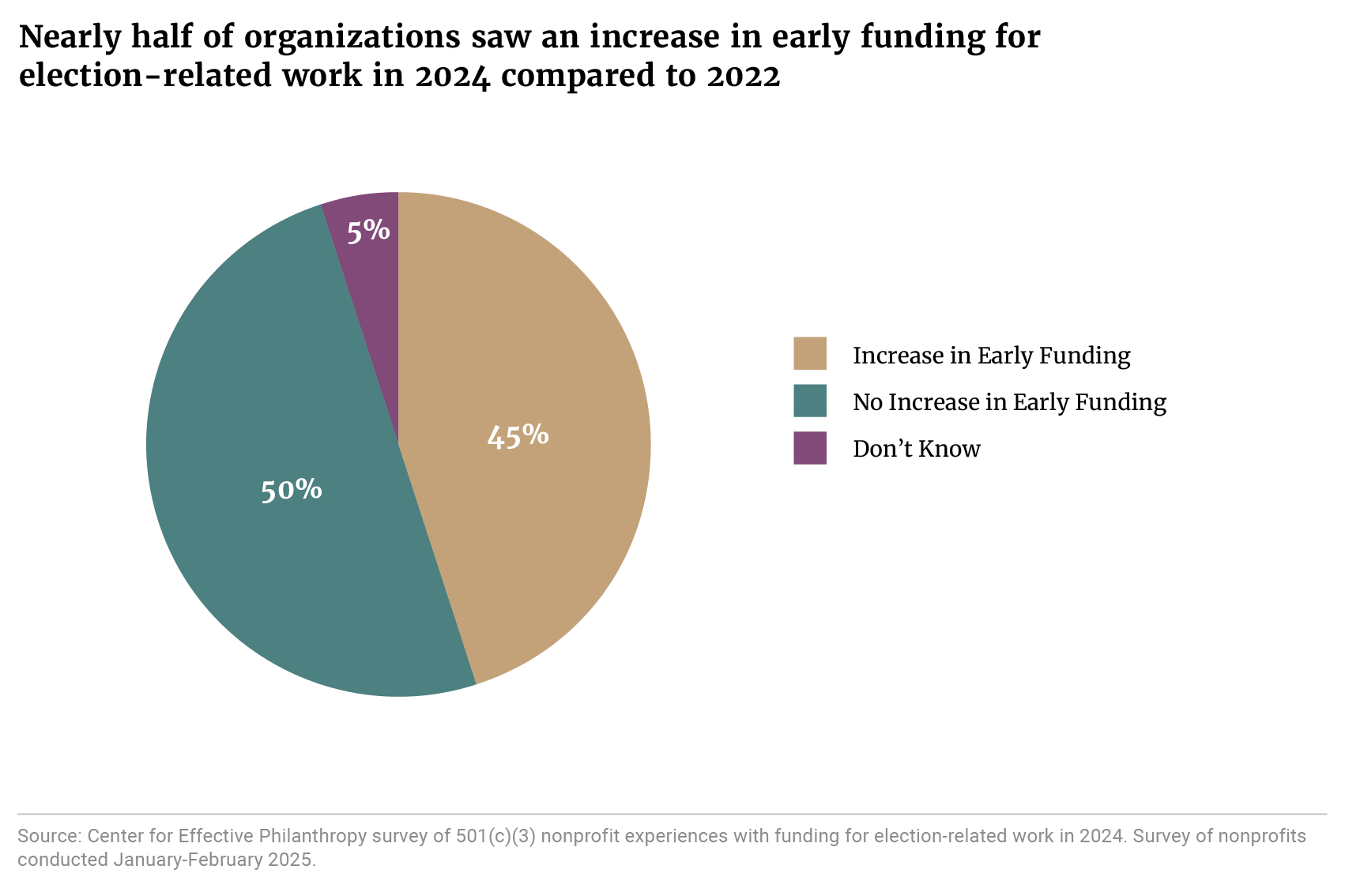

1. Nearly half of the nonprofits surveyed reported higher levels of funding during the first four months of 2024 than in previous election years.

We were encouraged to learn that survey respondents reported receiving greater levels of funding during the first four months of 2024, compared to 2022.

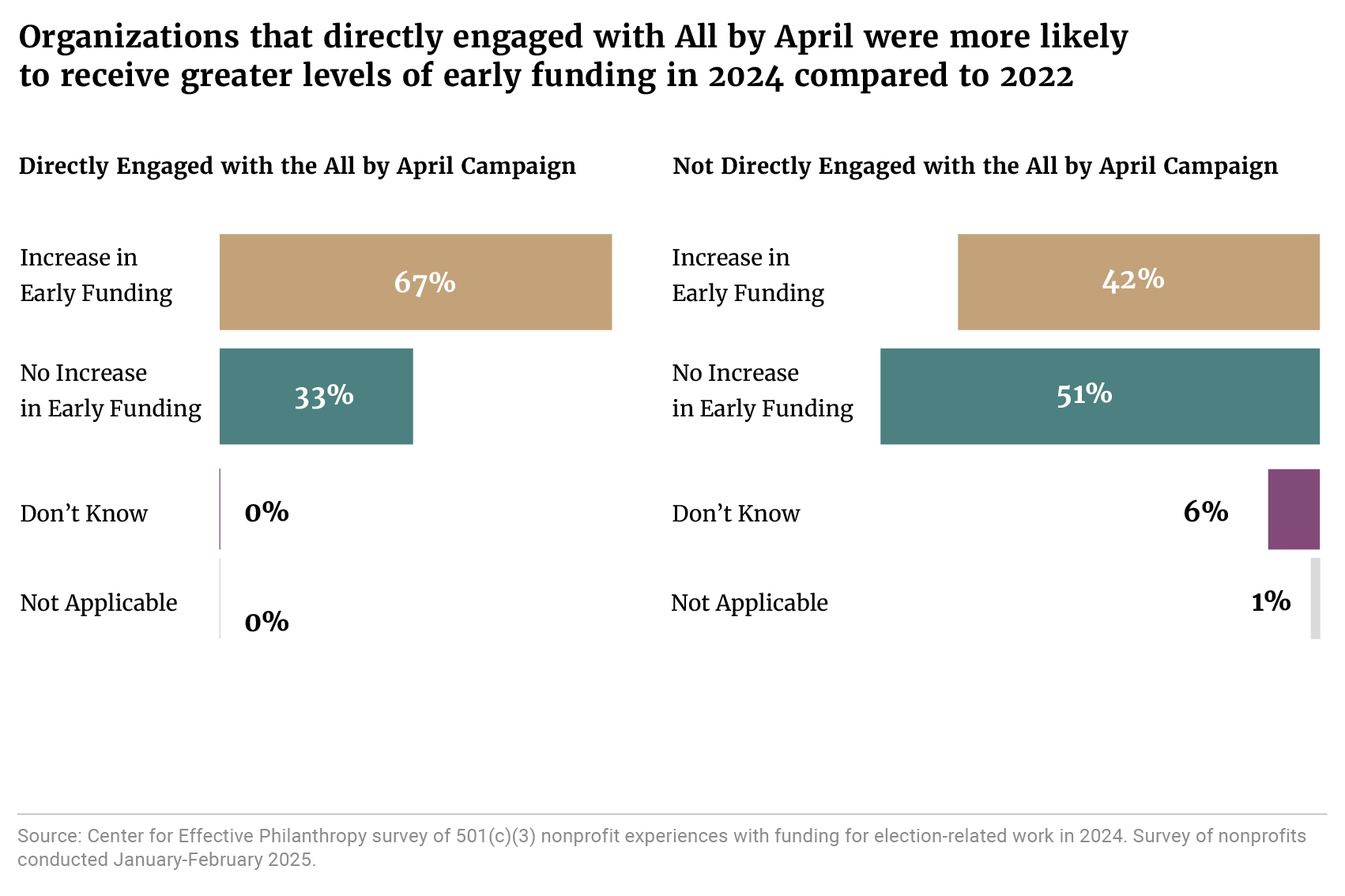

These rates were even higher for nonprofits identified as partners of All by April (67%) and intermediaries (58%).

When we looked at a comparison to the 2020 election cycle, we found very similar numbers to what survey respondents reported for 2022.

It’s possible that organizations that engaged with All by April may have received more funding because they learned about the campaign early and could build it into their fundraising practices for the year. Some qualitative responses from groups that didn’t engage with the campaign indicated that they were caught off-guard by the early opportunity to fundraise and struggled to adjust their fundraising timeline.

“We were grateful for the significant impact of All by April as we saw numerous of our current and prospective funders signing on to the pledge. It influenced several of our existing funders to expedite funding processes, and created opportunities for outreach to other democracy funders that we saw were aligned with our priorities and values.”

— Survey Respondent

“It was an open invitation to see which funders care about democracy. We were able to leverage that list and build new relationships which was great to increase funding and we did raise new dollars.”

— Survey Respondent

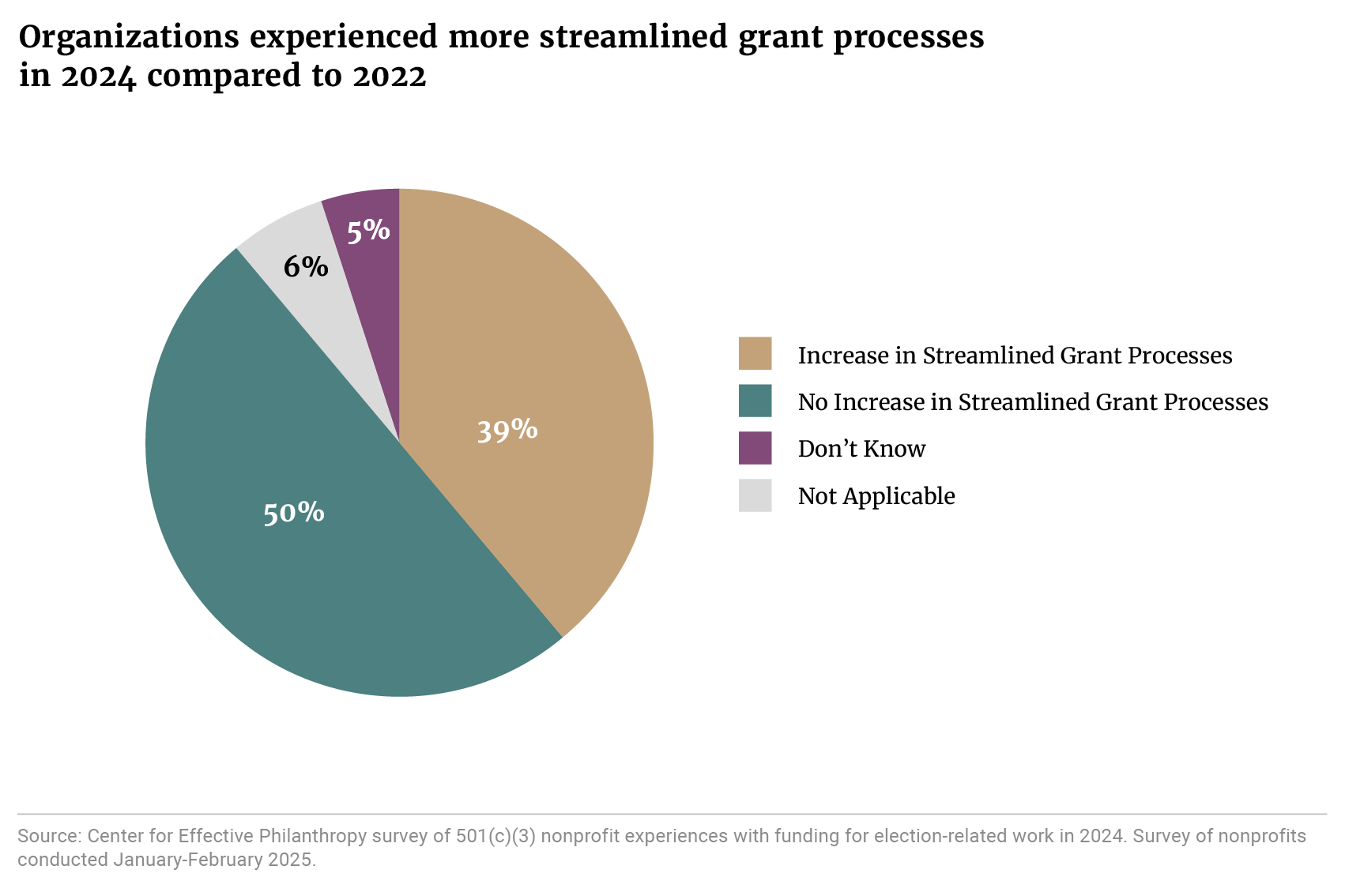

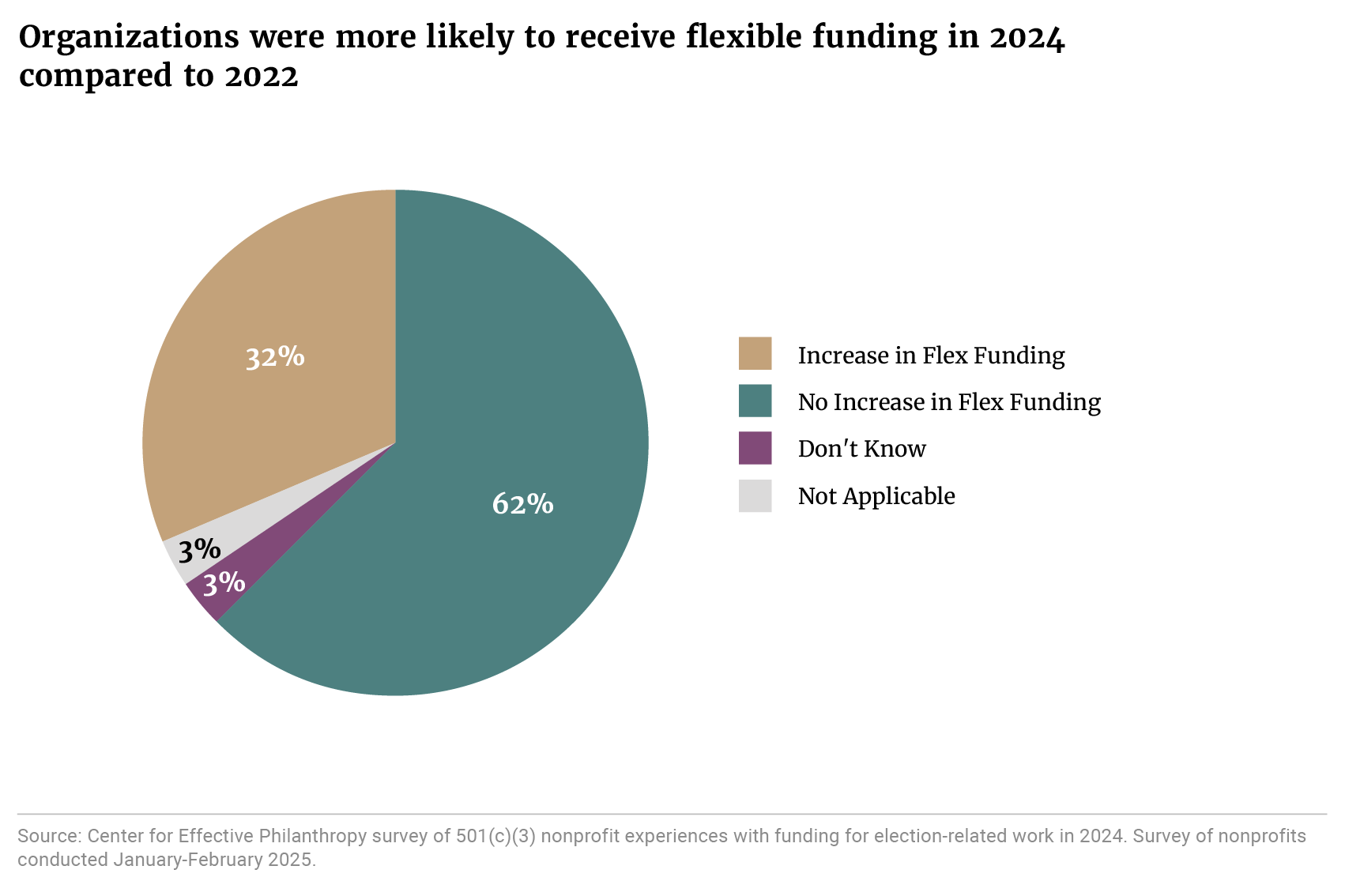

We were also encouraged to find that more than a third of respondents experienced more streamlined grant processes (like faster disbursement of funds or simplified administrative requirements) over the same timeline, and more than a quarter received more flexible funding (like unrestricted or general operating support).

The All by April campaign actively encouraged funders to adopt these practices. In our 2024 participating funders survey, we found that 62% of direct grantmakers were motivated to change their funding behavior in 2024. We also found that 55% of direct grantmakers reported that their behavior changes included changing their grantmaking policies or ways of working to support the goal of earlier giving.

“Wonderful! Rapid and flexible funding freed up earlier gave organizations breathing room for strategically planned work that is sustainable with team capacity considered for the long haul.”

— Survey Respondent

2. Nonprofits reported that receiving election-related funding by April is crucial — but they can do more if it’s even earlier.

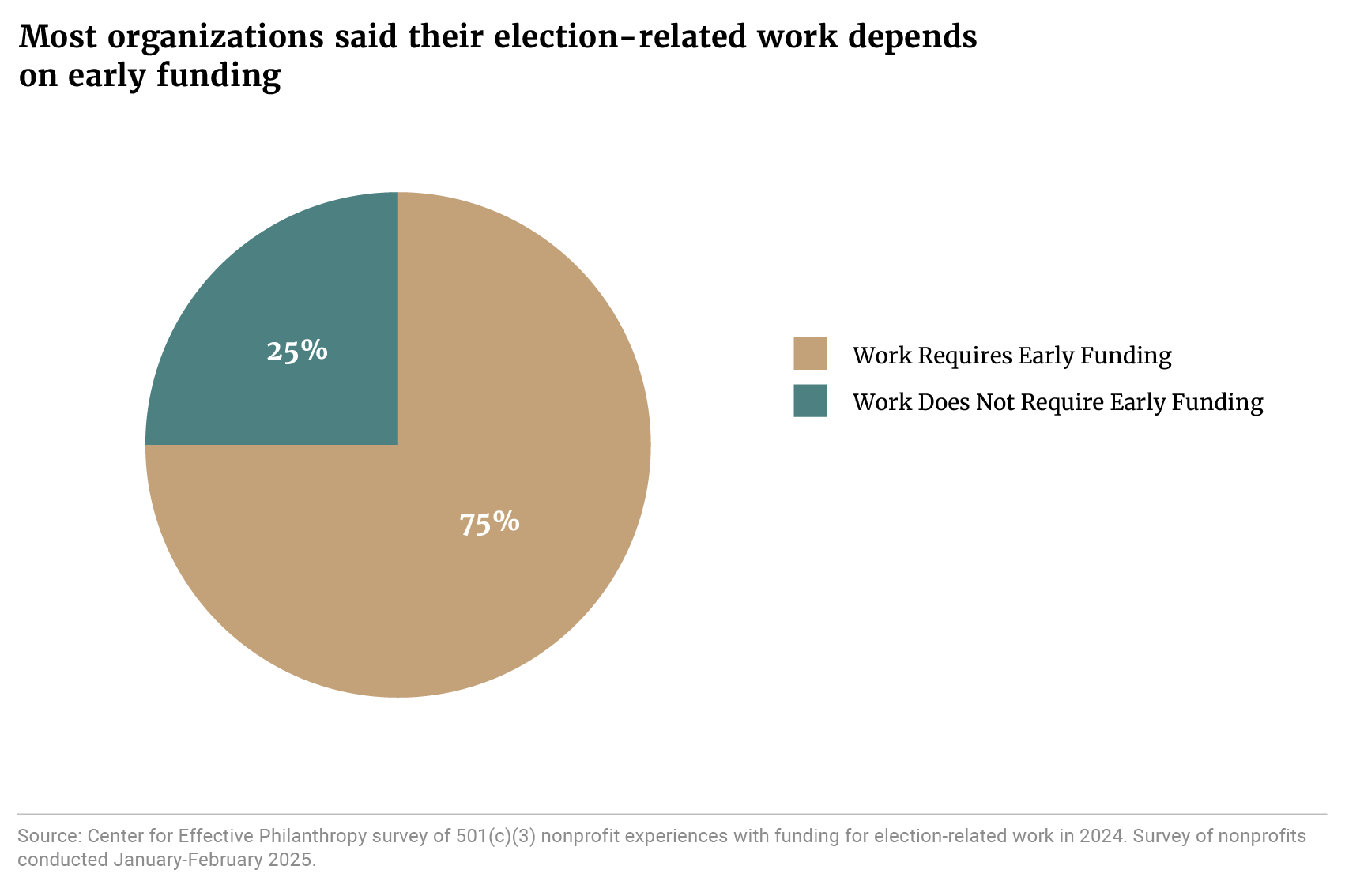

A majority (75%) of survey respondents indicated that their organizations engage in election-related work that is dependent on earlier funding — like hiring staff, training staff and volunteers, planning, and carrying out programmatic work.

As a result of receiving earlier funding in 2024, 42% of survey respondents – and a higher proportion of organizations with budgets less than $1 million or those with a grassroots focus – engaged in different or expanded election-related work.

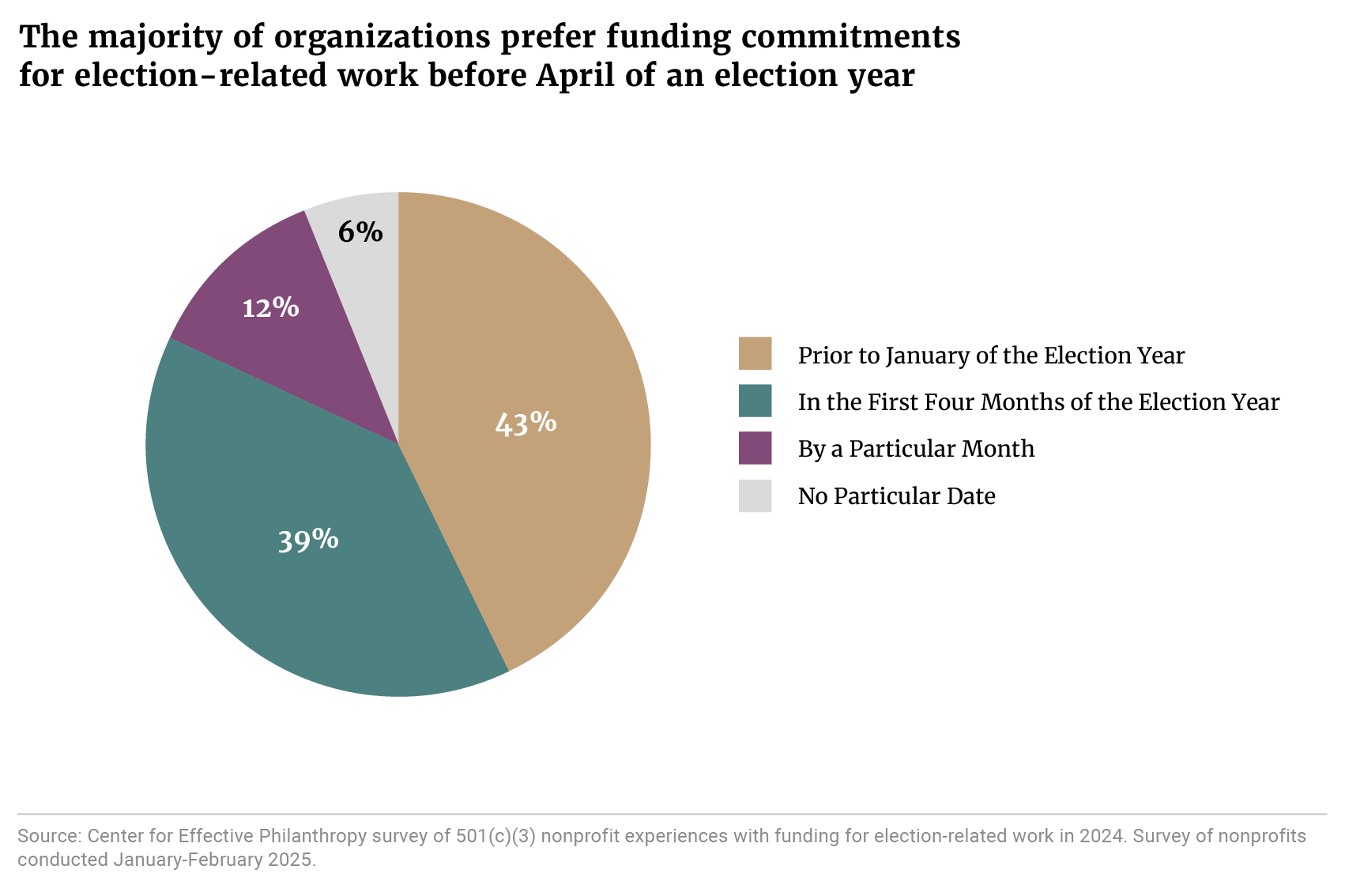

As expected, many survey respondents (43%) would prefer to receive election-related funding commitments before January of an election year. While some funding cycles may not be conducive to making grants before January, a commitment that the funds are coming can be fundamental for organizational planning.

An additional 39% of respondents reported that they would prefer to receive commitments during the first four months of the election year. Of the 12% that prefer to receive commitments by a specific month, June and July were the most commonly mentioned months.

“By receiving funds earlier, we are able to hire and train the staff necessary to conduct our programmatic efforts. When we are not able to do that, capacity issues arise. Current staff feel the burden of additional work needing to get done without the staff needed to do it. This affects the overall success of programmatic efforts and also morale.”

— Survey Respondent

“Early funds mean we can actually begin to do what we’ve planned on time. We can start hiring for the temporary positions that provide the added capacity we need during election years. If those folks aren’t onboarded by the end of the previous year, they aren’t there, ready to launch programs and recruiting when it needs to happen at the start of the year. We and our partners also aren’t able to make firm commitments to coalition plans if we aren’t fairly certain we’ll have the funds – and consequently the capacity – to follow through. Everything actually happening depends on getting funding, and not getting it early enough causes a cascading effect of pushing deadlines, paring down plans, and cutting losses.”

— Survey Respondent

3. Most nonprofits did not receive enough early funding to plan election-related work through the rest of the year.

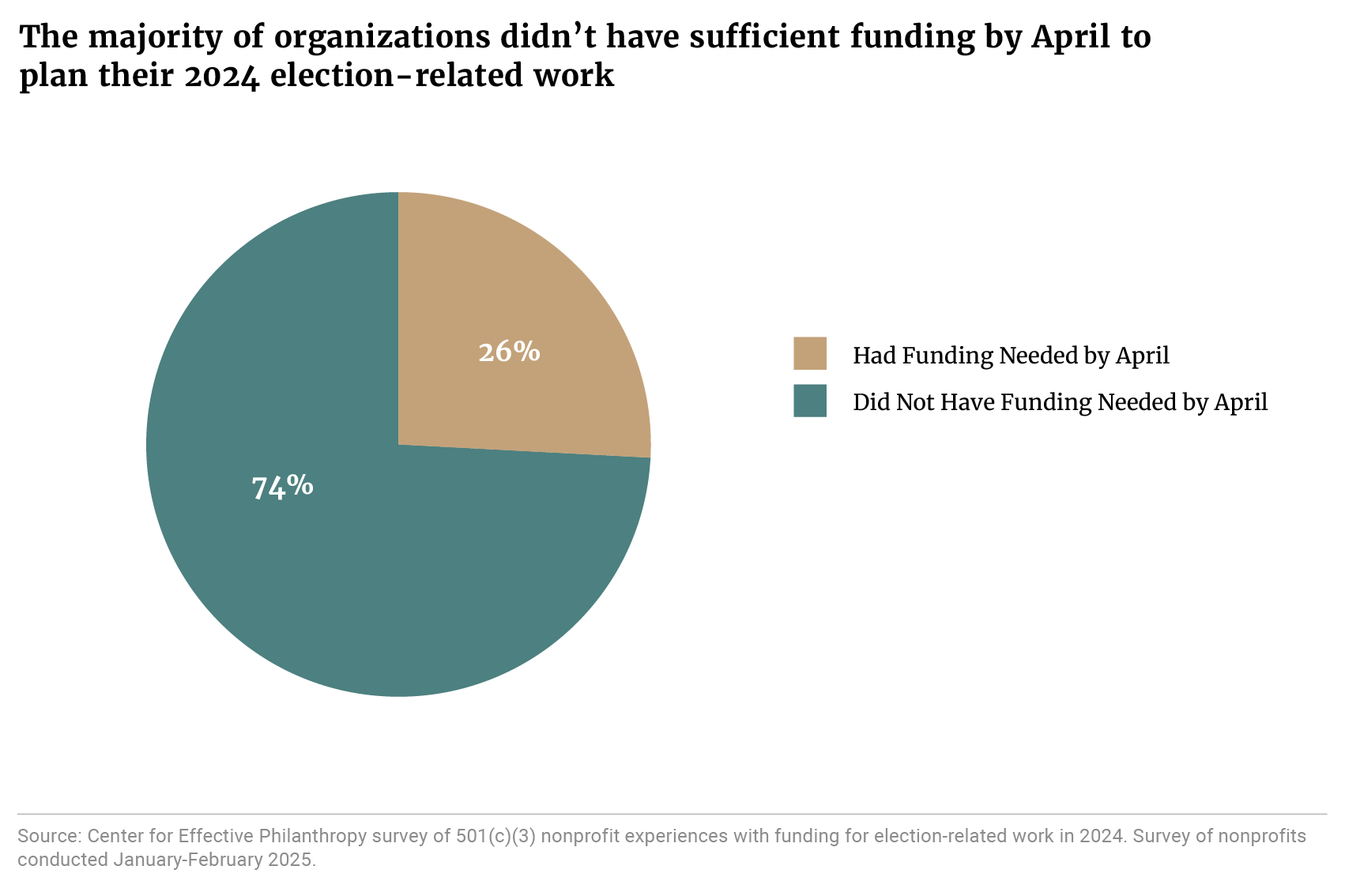

Overall, nearly 75% of survey respondents reported that by April 2024, their nonprofits did not have the necessary funding to plan for the needs of their election-related work through the rest of the year.

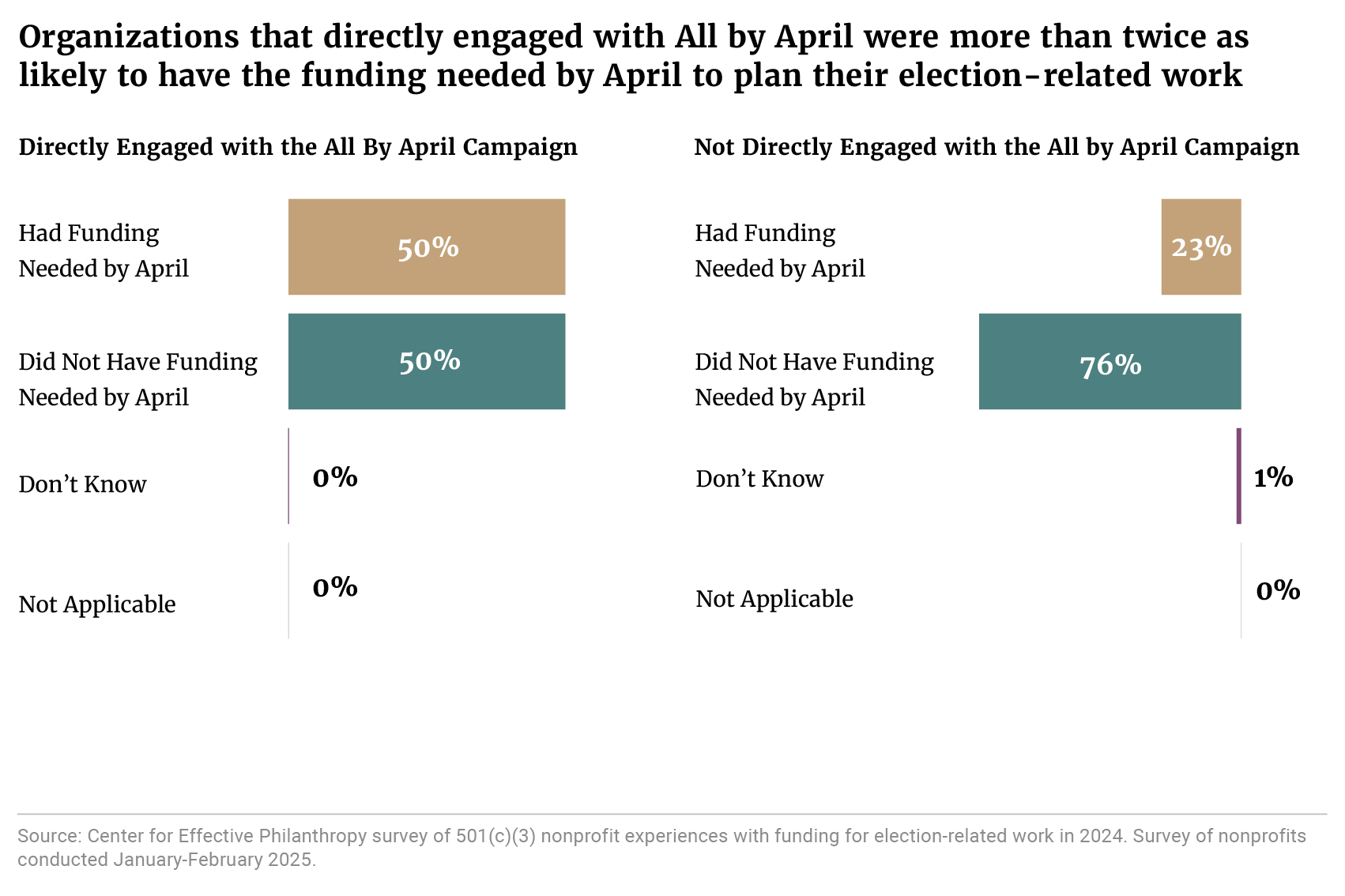

However, this number was significantly improved among nonprofits that had directly engaged with the All by April campaign. Only 50% reported that they lacked the funding they needed to plan for their election-related work through the rest of the year, including staffing and infrastructure.

Half of these survey respondents who did not have sufficient funding indicated that by April 2024, their organizations had a shortfall of 50% or more. Still, 43% of these organizations indicated that they were able to raise the necessary funds later in the year.

This aligns with what funders signing the All by April pledge reported in our survey last spring. Even with an increase in early giving, 41% of funders indicated that they would continue giving about the same amount in the post-April period as they would in a normal election year (and 2% would give more).

That said, there were a lot of organizations who were unable to catch up after reporting a budget shortfall in April. Of those reporting insufficient early funds, 57% were not able to raise the remaining funds by the end of the year. One survey respondent noted that 2024 was “a difficult fundraising year for our organization,” and another described the period as “the toughest election cycle in my twenty years of raising money for election work.”

While the All by April campaign demonstrated that earlier funding commitments can have a notable impact on budgets, the issue is much bigger than timing. Organizations don’t just need earlier funds, they need more funds. Philanthropy must work to close the budget gaps that organizations are experiencing.

Philanthropy must get dollars out earlier, and in greater amounts.

Democracy Fund’s recent survey of democracy funders indicated that nearly 4 in 10 (39%) plan to revisit their long-term strategies in 2025. This is an opportunity to adapt philanthropic strategies to include practices that empower the elections and voting field by:

- Increasing election-related giving;

- Planning earlier grantmaking in election years; and,

- Creating grantmaking processes that are a lighter lift for grantees.

At Democracy Fund, we’re committed to getting our 2026 election and voting grants made as early as possible. The target month of April was a good start, but we can do better. More to come on this soon.

As we plan for the next election cycle, we’re continuing to look for ways to make our grantmaking processes a lighter lift for grantees. Things like streamlining the grant application process, and offering simpler reporting methods can really help. We’re working on some shifts internally, and we encourage our peers to explore options like these as well.

Lastly, we’re supporting the Courage Calls Us Campaign. This campaign is answering the call for increased funding by pushing for an initial investment of $20M across the field to fund streamlined responses to today’s most urgent challenges. Please reach out if you have any questions — we’d be happy to discuss.