Part of “Stewards of Democracy,” a series on findings from the 2020 Democracy Fund/Reed College Survey of Local Election Officials

The 2020 election year was historic on many fronts. A decades-long deepening of political, social, economic, and cultural divides made for a tremendously volatile and competitive electoral landscape. What’s more, as a global pandemic took hold, many wondered how it would be possible to hold free and fair elections amid such a public health crisis.

As part of our 2020 Democracy Fund/Reed College Survey of Local Election Officials (conducted in summer 2020), we asked local election officials an extensive battery of questions about how they were preparing for the upcoming November election, including a special set of questions tailored to COVID-19 challenges.

The Realities of Different Jurisdiction Sizes

In each blog post in this series, we have pointed to the significance of jurisdiction size when describing and understanding the local election environment and the role of the local administrator.

Election readiness is no different and, accordingly, pandemic-related issues didn’t impact all local election officials in the same way — even if they were serving in the same state. Some large jurisdictions received a lot of media attention in 2020 because they had so many polling places and long voter lines. But small jurisdictions faced many of their own challenges as they worked to rapidly respond to shifting requirements and implement new procedures.

The fundamental distinction relates to workload, support, and staff. Local election officials in the smallest jurisdictions are more likely to wear several hats as town clerks, county recorders, or other roles. Elections work amounts to a small proportion of the job responsibilities for about half of small-jurisdiction officials, and as a result, these officials had even less working time to adjust to the realities of running elections amid a pandemic.

Additionally, small jurisdictions are much more likely to have a very small staff: About 75 percent of local election officials in jurisdictions that have under 5,000 voters are the sole individual administering elections in their jurisdiction, and many of these are only part-time workers.

Preparing to serve a few hundred voters is obviously a very different enterprise than doing so for millions of voters. Nonetheless, we flag for the reader that the ability to adapt to the new demands placed on local election officials in 2020 may have been crucially dependent on size, staff, and other resources. Simply having a larger election office allowed for some redundancy and support during the pandemic. We heard from a number of local election officials in small jurisdictions that a single positive COVID-19 test would require them to close their offices for 14 days because their small teams all work in close proximity. An official working in a larger jurisdiction would be able to rotate staff or lean on other parts of the organization to avoid such an impact.

Election Preparedness and COVID-19

Small jurisdictions were the least likely to say that they had to adjust their election planning in light of COVID-19. While all of our respondents in jurisdictions with more than 100,000 registered voters said that they had to adjust to the pandemic, only about 85 percent of local election officials in jurisdictions with under 25,000 registered voters said the same. We suspect these differences may be simply a function of scale — adjusting for things like socially-distanced voting is probably easier in rural settings and small municipalities.

One of the specific changes that we were interested in was whether local election officials would have to consolidate polling places, leaving some voters farther away from a voting location than normal. Consolidation of polling places became a flashpoint for political and legal conflict during primary elections in the spring and summer.

By mid-summer when our survey was being conducted, only about 10 percent of local election officials were considering precinct consolidation during the November election in response to COVID-19, although for larger jurisdictions this proportion reached about 30 percent. Larger jurisdictions are more likely to have many polling places, while some smaller jurisdictions might have only a single voting location that cannot be shuttered.

When asked why they were considering consolidating some polling locations, a clear majority of respondents cited facilities constraints as part of their reasoning, and slightly under half cited poll worker issues. Resource and staffing constraints were much less common, and very few respondents said that they were required by the state to consolidate locations.

When asked about their preparations for conducting the election amid the pandemic, local election officials expressed a fairly high degree of confidence across a number of dimensions, such as having enough personal protective equipment (PPE) for their staff and volunteers, safely accommodating staff and volunteers in the workplace, and being able to utilize their permanent workforce and traditional polling places.

Presented with a set of questions asked in previous years to understand staffing and resources, local election officials expressed high levels of confidence in their ability to obtain accessible voting machines and polling places but much less confidence in obtaining poll workers, particularly bilingual poll workers. Note that our figure below shows confidence levels only for respondents who agreed that a given resource applied to them. While 95 percent of our survey participants responded that the first three resources applied to them, only 40 percent said having bilingual poll workers did, which corresponds with the proportion of those federally required to have such support. Thus, the lack of poll workers with bilingual skills is likely to be even more acute than our data reflect.

Where Local Election Officials Found Support in Responding to the Pandemic

With so many local election officials reporting that they had to change their processes in response to COVID-19, we wanted to know what sources they turned to for information and which were most helpful.

Officials were most likely to seek resources close to home: in their local jurisdiction or to state elections offices, state associations, and/or state health authorities. About 35 percent of respondents consulted information from the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) directly, and other federal and national groups were referenced less frequently. Some state election directors and state associations may have used resources from federal and non-governmental organizations to inform their recommendations.

Information from state elections offices and professional organizations was also deemed to be the most helpful, compared to most of the other sources (all of which received similar ratings). Local election officials participating in our survey also had the option to write in a resource they consulted if not reflected in our list. We were not surprised to learn that those who chose to do this also rated their write-in resources very highly overall. These other resources included local emergency management departments, regional election official groups, the United States Postal Service, and local and national news sources.

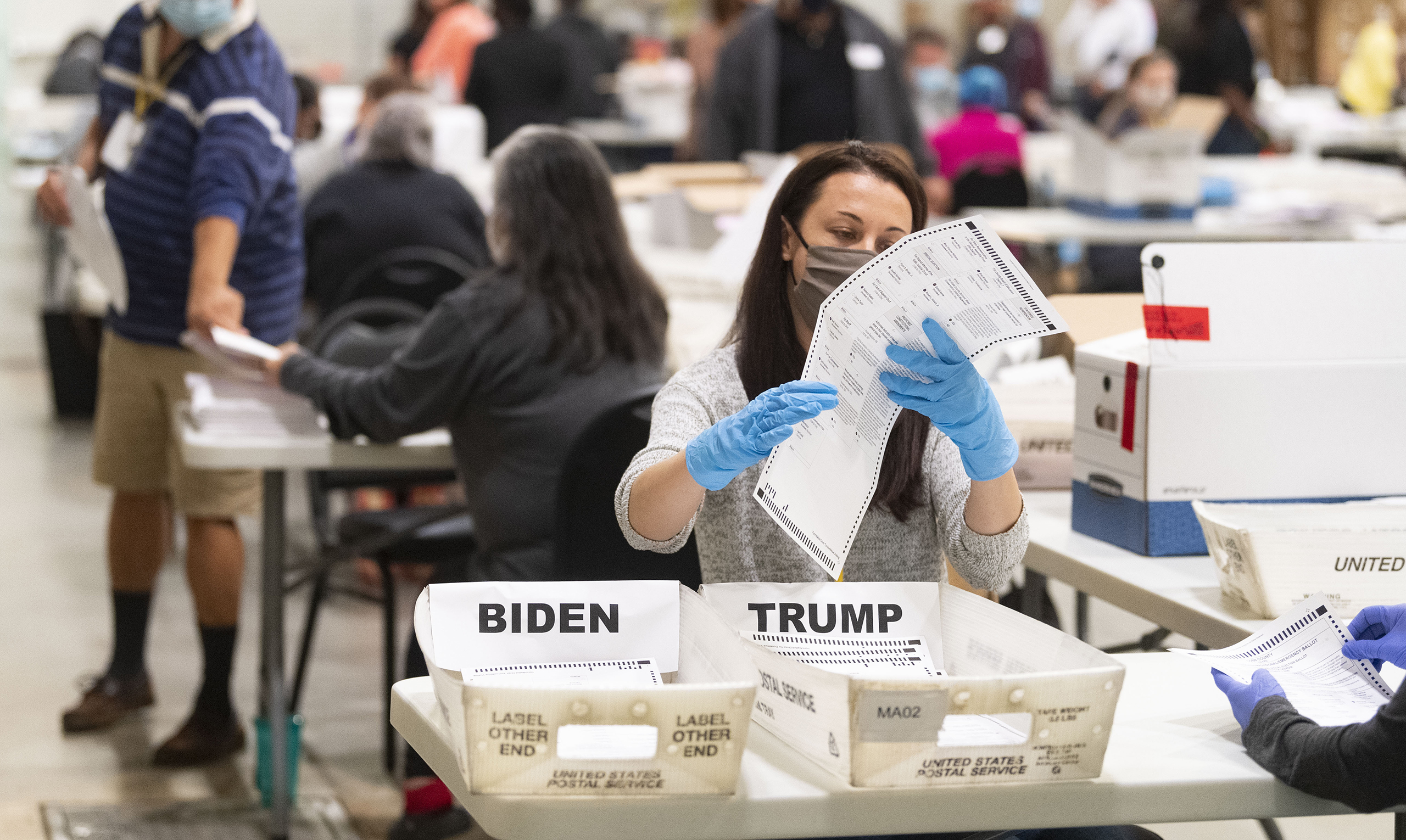

Managing a Surge in Absentee Voting and Voting by Mail

One of the biggest effects of the pandemic on voting was a large increase in voting by mail. States came into the November 2020 election with varying levels of experience conducting elections by mail. At that point, five states conducted all elections by mail, and five states allowed any voter to sign up for permanent absentee voting and automatically receive a mail ballot for each election. In the November 2016 election, about 20 percent of the public voted by mail, but this varied from less than 5 percent in states that required an approved excuse to vote by mail to more than 87 percent in states that conduct all elections by mail.

Responses to a series of questions about mail voting preparation indicate that the majority of administrators felt prepared to run an expanded vote-by-mail system in November 2020. As expected, this varied based on the state’s prior experience with widespread mail voting. Most officials felt confident that they could obtain enough ballots and envelopes to meet expanded demand for mail voting; those in states with less vote-by-mail experience were about 15 percentage points less likely to feel confident than those in experienced states.

Other measures of mail voting preparation showed a wider spread between more experienced and less experienced states. Close to 95 percent of officials in states with more mail voting experience were confident that they had sufficient staff and resources to process increased numbers of mail ballots; fewer than 65 percent of officials in states with less experience shared that confidence. Similarly, officials in states with mail voting experience expressed higher confidence than other states — by more than 25 percentage points — that their state’s timeline was sufficient for all of the steps involved in requesting, mailing, returning, and processing mail ballots. The gap between more and less experienced mail voting states was much smaller on the issue of whether voters were sufficiently informed about the standard U.S. Postal Service delivery times that would impact whether a ballot arrived in time to meet state deadlines and be counted.

Overall, local election officials felt relatively confident about their process heading into November 2020. Over 90 percent said they would be fully prepared to administer a safe, secure, and accessible election. As we have seen in other results, election officials are less positive in their assessment of things outside of their control. For example, one in five raised concerns about whether they would have adequate funding for their jurisdiction or whether the other offices in the state would be sufficiently prepared for November, and under half said that offices across the country would be prepared to run a safe, secure, and accessible election.

Stewards Rising to the Challenge

The 2020 election was historic and an outlier in many respects, but some of the changes and lessons it generated may endure. Some pain points reported by our respondents in that year — sufficient bilingual poll workers and insufficient resources and trained staff — may have been magnified in 2020 but have been evident in prior years of this research.

Moreover, local election officials accomplished something extraordinary in 2020. They engaged a variety of resources, and through rapid learning and adaptation early in the pandemic, took a range of steps to protect voters and workers during a public health crisis. They prepared for more Americans than ever to vote by mail, even in states less experienced with the practice. And generally, they felt well prepared to deliver democracy, even under these conditions. In rising to the challenges of 2020, election officials revealed not only their competence, dedication, and grit, but also possibilities and potential for further strengthening our election system.