In 2020, two dozen Atlanta journalists gathered to take a hard look at the state of local media in Atlanta. A lack of diversity and commitment to community meant that many newsrooms weren’t responsive to the people they were supposed to serve. And on top of that, cuts and downsizing meant that there were fewer and fewer reporters to cover important things like local elections and education policy.

Local Foundations Need Solid Local Journalism if They Hope to Advance Their Missions

First the good news: Philanthropy is starting to respond to the demise of local journalism with the urgency it deserves. In the past few years, major national efforts, such as the American Journalism Project, Report for America, and NewsMatch have generated well over $200 million in philanthropic giving to news organizations across the United States. NewsMatch’s annual gift-matching campaign, which kicked off November 1, raised a record $47 million in individual donations in 2020 alone.

Envisioning a Just and Open Digital Democracy: Expanding Our Commitment to Platform Accountability

Last month, after Facebook attempted to undermine the efforts of independent researchers — and Democracy Fund grantees — who were studying the effects of the platform on democracy, our President joined fellow NetGain Partnership leaders in releasing a joint letter calling for greater platform accountability and transparency. That open letter from some of the nation’s leading foundations noted:

“Our foundations share a vision for an open, secure, a nd equitable internet space where free expression, economic opportunity, knowledge exchange, and civic engagement can thrive. This attempt to impede the efforts of independent researchers is a call for us all to protect that vision, for the good of our communities, and the good of our democracy.”

Days later, the researchers who Facebook had sought to silence released a major study that illustrated how high the stakes are. Their research showed that during the 2020 election people found and clicked on misinformation on Facebook far more than accurate, factual news — further evidence that social media platforms are harming our democracy by amplifying content that accelerates hate, division, and misinformation.

At Democracy Fund, there’s never been a question as to why we would support and advocate for platform accountability — it is central to our reason for being. In this moment, we have unprecedented opportunities to make social media companies liable for their harms, to rein in the worst aspects of their business model, and to force changes in how they operate. If we are successful, we can move toward a world where social media companies enable multiracial and pluralistic democracy, instead of fracturing it, where facts are amplified, rather than discounted, and where there is accountability for hate speech and incitements to violence.

It took some careful and collaborative thinking for us to determine our theory of change, as well as what our support on this issue could look like. To meet this moment, here at Democracy Fund, we have started to significantly increase our grantmaking to nonprofit organizations who are working deeply on these issues, and often at the intersection of advocacy, public will-building, and litigation. We’re deepening our partnerships with a mix of grassroots organizers, researchers, communicators, lobbyists, and litigators, and building on our work with the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law.

At the heart of our grantmaking will be Black and Indigenous people, and people of color, and the harms they face as a result of social media platforms. Conspiracy, extremism and prejudice are magnified on social media in ways that are vastly disproportionate to their actual representation in society and are normalized by the spread from harmful algorithms and networks.

Together, our grantees will be working on three key areas to transform our digital public square:

- Anti-Discrimination and Data Privacy: Ensuring that social media companies and their systems cannot use personal data to discriminate or track and target people in ways that lead to disparate impact;

- Platform Liability: Transforming the policy frameworks for how social media platforms are held liable for the online and offline harms their systems and choices produce; and

- Transparency: Opening up social media platforms to new levels of transparency regarding the impact of their systems on our democracy and civil rights to enable audits and reporting by journalists, researchers and policymakers.

This work will spread across communities, courtrooms and the halls of congress, and will be built on a growing movement of organizations working at the intersection of civil rights and platform accountability. We are grateful for the work that others have done in this space and know we can’t do it alone. As Democracy Fund President Joe Goldman has said, “tackling democracy’s cybersecurity problem requires collective action” and our efforts will do just that. We’ll share more about this growing area of work soon.

If you’re interested in learning more, or partnering with us in this effort, please drop me a line at pwaters [@] democracyfundvoice.org.

A call for funders on 9/11: invest in Black, African, Arab, Middle Eastern, Muslim, and South Asian communities

Democracy Fund is joining funders in a pledge to raise $50 million over the next five years to support Black, African, Arab, Middle Eastern, Muslim, and South Asian (BAMEMSA) communities deeply impacted by the United States’ response to 9/11. We are proud to join in this effort together with Open Society Foundations, Ford Foundation, and The RISE Together Fund (a donor collaborative of the Proteus Fund) and encourage other funders to do the same.

Over the past four years, we have seen a rise in dangerous rhetoric and policies targeting BAMEMSA communities, such as the Muslim, African, and asylum-seeker travel bans. There continues to be a relentless amount of money dedicated to funding Islamophobia and hate. At the same time, many leaders in BAMEMSA communities are on the frontlines fighting for an end to discriminatory policies and legislation.

Democracy Fund has dedicated a grantmaking portfolio to BAMEMSA-led organizations as they challenge infringements to their civil rights and combat polarizing and racist narratives. As part of this work, we have supported BAMEMSA-led funding collaboratives who help build the “critical social infrastructure”* of BAMESA communities, as well as a number of BAMEMSA led organizations. These grantees include:

- RISE Together Fund, the first donor collaborative dedicated to supporting BAMEMSA groups. Their support of grassroots organizations and collective advocacy efforts has contributed to decisions like the executive order rescinding the Muslim, asylum and African bans.

- Pillars Fund, a Muslim-led foundation, is building on a decade of funding community organizations. In 2021, they launched their Pillars Artist Fellowship to promote more complex and accurate representations of Muslims in media.

- The Institute for Social Policy & Understanding (ISPU), which educates and trains journalists across the country to accurately cover Muslims and issues impacting them. Their work reaches millions of people in diverse outlets such as the Chicago Tribune, NPR, and the Washington Post.

We invite you to read the letter we signed and consider joining us in supporting the BAMEMSA community. The attack on civil rights, violation of norms, and unfettered hate speech we have seen over the past 20 years harms our democracy and makes our society more vulnerable to fissures and violence. Supporting BAMEMSA communities is crucial to the fight for a more open, just, and inclusive society and democracy.

BAMEMSA-led grantees of Democracy Fund’s Just and Inclusive Society Project include:

- Arab American Institute

- Asian Americans Advancing Justice – Asian Law Caucus

- CLEAR CUNY

- El-Hibri Foundation

- Horizon Forum, a fiscally sponsored project of Proteus Fund

- Millions of Conversations

- Movement Law Lab

- MuslimARC

- Pillars Fund

- Proteus Fund — RISE Together Fund

- South Asian Americans Leading Together

- The Institute for Social Policy and Understanding

*Brie Loskota, Executive Director of the Martin Marty Center at the University of Chicago Divinity School, uses this term to describe the organizations, practices, norms, and relationships that make up a healthy society.

Want to support accurate journalism? Fund solidarity reporting.

Last summer, solidarity became a national buzzword. Thousands of people declared and demanded solidarity against racism in the wake of police murdering George Floyd and Breonna Taylor. Some news organizations swiftly moved beyond the statement by implementing and amplifying solidarity reporting: the practice of going directly to marginalized communities to inform accurate coverage instead of relying on authorities and elites to tell the story. But many news outlets did not go this route, and remain caught between a desire to appear neutrally “balanced” and the growing understanding that mistaking balance for accuracy can promote misinformation with grave repercussions.

As journalism funders regularly pledge to support accurate reporting, it’s time to be more specific – and more discerning – about what qualifies as accurate reporting, particularly in coverage of marginalized people.

Journalistic accuracy must be substantive — not surface-level

News organizations often achieve surface-level accuracy by amplifying the words they hear on a police scanner or during a press conference without mistyping or omitting any talking points. The problem is that accurately repeating what someone says doesn’t mean their statements are true: distortions, decontextualized self-validation, and outright lies are common. And as we know from research in the last five years alone, fact-checking after publishing doesn’t easily fix misinformation.

Substantive accuracy, on the other hand, is a hallmark of solidarity reporting and means more than centering institutions of power and people employed by them. It means amplifying the voices of those who live the news every day. These reporting practices represent affected communities first.

Think of it this way: if a reporter were writing a story about injustice affecting the house you live in, who would know the most about it? The answer is likely you. Imagine, though, that the reporter never reaches out to you. Instead, they speak with the city council, police officers, and your landlord or mortgage lender. This story might provide surface-level accuracy through amplifying “expert” voices, but it would lack the substantive accuracy that your perspective, as the most directly affected person, would provide.

Members of marginalized communities don’t need to imagine this scenario. They live it every day when even the best-resourced local news outlets persistently quote credentialed experts, law enforcement, and bureaucrats at the expense of representing the people who are living, struggling, and dying due to the unjust conditions under discussion.

Solidarity journalism prevents misinformation

Surface-level accuracy sets the stage for journalism to amplify misinformation, while substantive accuracy through solidarity practices remedies it.

Let’s consider a recent example: When police murdered George Floyd, the initial report made no mention of a police officer’s knee on his neck. At a surface-level, it is technically true that this report said, “Officers were able to get the suspect into handcuffs and noted he appeared to be suffering medical distress.” It is far from true that this report accounts for how George Floyd died. We know this because of more reliable sources who lived the moment. Four children who witnessed the murder provided the most accurate account of what happened. And in March 2021, in stark and undeniable contrast to the original police report, they provided accurate court testimony about how George Floyd was killed.

Cases like this make it so clear that when reporters center sources with institutional power and stop there, the public does not get a substantively accurate story. All too often, surface-level reporting further amplifies misinformation. Fortunately, we know that solidarity reporting can address this problem.

Solidarity reporting strengthens substantive accuracy across a range of issues

Any newsroom that covers timely and important issues should provide substantively accurate coverage. Solidarity reporting improves accuracy across a range of these issues and communities, including:

- COVID-19, by addressing and accounting for the disproportionate impact on Black and brown communities in the U.S. and abroad – even when elected leaders deny the crisis.

- Anti-Asian violence such as the Atlanta shooting, by representing the perspectives and experiences of Asian and Asian American people.

- Extreme weather, by focusing on the dangers and struggles for people who must go without electricity and water for an indefinite amount of time.

- Gun violence, by centering the perspectives of families of victims and survivors and reporting on continued calls for specific action from within affected communities.

As news organizations promise to learn from their past mistakes, journalism funders can support solidarity reporting as a way to help news outlets move beyond statements and apologies and toward achieving greater substantive accuracy.

A call for funders: Supporting accurate reporting means supporting solidarity reporting

Funders have the power to accelerate a trajectory toward a more accurate, ethical, and equitable news ecosystem. As more foundations invest in a growing range of news outlets, news initiatives, and news partnerships, solidarity reporting offers a set of criteria that funders can use to make – and justify – their decisions.

Next time you’re reviewing a proposal, ask yourself these three questions to understand how or if solidarity is part of the reporting process:

- Is the project aligned with substantive accuracy in journalism, which means including the perspectives of people directly affected by ongoing injustice?

- Are the terms, frames, and definitions of the project aligned with affected communities’ self-described needs?

- In the face of injustice, will leadership and contributors be able to name it and stand against it, or is the project structurally tied to maintaining a façade of neutrality?

A minimal standard of surface-level accuracy in journalism cannot suffice. Such a low standard breeds misinformation about marginalized communities and perpetuates harm against them. It’s time to support solidarity reporting and the substantive accuracy within it to help build a more just future.

Anita Varma, PhD leads the Solidarity Journalism Initiative. She is an incoming assistant professor at UT Austin’s School of Journalism & Media and senior faculty research associate at the Center for Media Engagement. Previously, she was at the Markkula Center for Applied Ethics (Santa Clara University). The Solidarity Journalism Initiative helps journalists implement solidarity in their reporting on marginalized communities. If you are a journalist or journalism supporter and would like to learn more about Solidarity Journalism, please contact anita.varma@austin.utexas.edu. You can also follow her on Twitter.

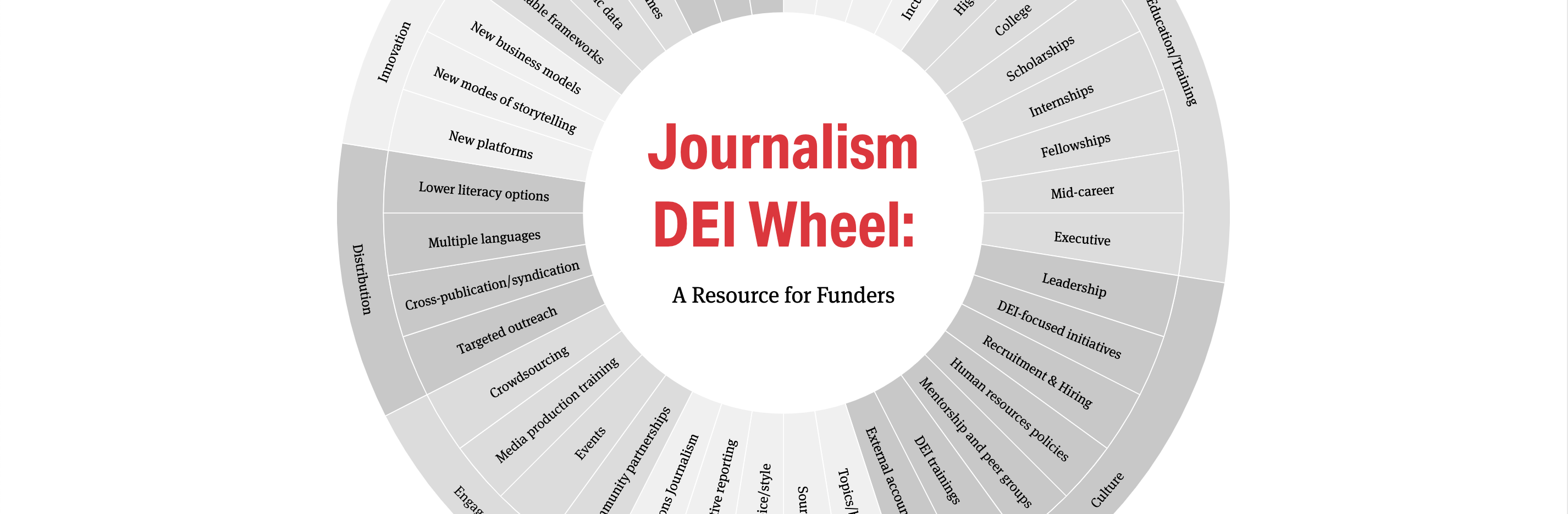

The Journalism DEI Wheel

The Journalism DEI Wheel is an interactive tool designed to help funders in particular inform grantmaking by seeing the bigger picture on a higher level, with useful examples and resources for further illumination.

Funders can explore the spokes of the Journalism DEI Wheel to see how equity in journalism is currently being addressed across key areas: education and training; organizational culture; news coverage; engagement; distribution; innovation; evaluation; the larger journalism industry; and funding.

Each area is divided into smaller points of intervention. For example, if you click on “Education/Training,” you will see opportunities to advance DEI in journalism through high school programs, college programs, scholarships, internships, fellowships, mid-career programs, and executive training.

Click on any one of these to learn more and find specific examples, including lists of relevant initiatives on the Journalism DEI Tracker.

How Metro Atlanta Has Become a Major Ethnic Media Hub, Serving Immigrants and Refugees

Last June, Mayor Edward Terry walked into the Clarkston Community Center’s meeting hall for a panel discussion on the upcoming census. The hall was packed with community leaders, legislators, refugees, and immigrants. For a small city located east of Atlanta, Clarkston has become the most ethnically diverse square mile in the United States.

“I am truly honored to welcome you to our city, known as the Ellis Island of the South,” Terry said. “The ethnic media in this room plays a very important role to inform our residents who come from every corner of the world.”

Since the mid-70s, Clarkston has welcomed Somalis fleeing civil war, Bhutanese fleeing ethnic cleansing, as well as Cambodians, Nepalis, Croatians, Eritreans, and Liberians escaping violence and religious persecution in their home countries. Now, as Clarkston continues to attract refugees and immigrants from Asian, Central American, and African nations, the city — and metro Atlanta as a whole — has become one of the major hubs of ethnic media in the country.

“Every day, we have programs that are aired in at least 10 languages. And the hosts, mostly volunteers, also have first-hand knowledge of the cultural nuances of their own communities,” said Hussein Mohammad, a founding member and former director of Sagal Radio, a small Clarkston-based radio station that broadcasts in Swahili, Sino-Tibetan, Tigrinya, and Arabic, to name a few.

Recently arrived immigrants from South Korea have also made metro Atlanta their home.

“You go to Duluth [which is part of Gwinnett County, about 27 miles from Atlanta city center], you would think you are not in the Deep South. With rows and rows of Korean establishments, and hundreds of thousands of Koreans who live there, it feels more like Seoul,” said Jong Won Lee, former editor of Korea Daily. “If you speak English, you’d be the minority.”

Notably, metro Atlanta has a huge Korean ethnic media market, perhaps on par with those in Los Angeles and New York. In Gwinnett County alone, the Korean population increased by 155 percent from 2000 to 2017. These numbers don’t take account undocumented Korean immigrants, who tend to be undercounted. When I spoke with Eugene Rhee, Program Director of the Center for Pan Asian Community Services, several years ago, he underscored that the community has a different count of Korean population. By their estimates, there has been a 1,000 percent increase in the Korean population in Duluth — or Gwinnett County — over the last 15 years.

The Atlanta area now has four major Korean news outlets — three dailies (Korea Daily, Korea Times, and Chosen Daily) and a television station WKTB-CD, which is owned by Korean American TV Broadcasting.

The Chinese immigrant population has also been growing quickly, and so are Chinese-language publications. Less than a decade ago, The World Journal was the only Chinese-language publication in the area. Now, there are three other Chinese newspapers within the city limits, namely Atlanta Chinese News, China Tribune, Duowei Times, and The Epoch Times — the Chinese-American media network that covers 21 languages and 33 countries.

“More and more Chinese people are moving into Atlanta and buying properties. They think that Atlanta has more affordable real estate properties, better weather and friendlier people,” said Lily Lee, former publisher and editor of The World Journal Atlanta. “Soon, we will have our own Chinatown here.”

And according to the Pew Research Center, Atlanta ranks 19th among the sixty largest metro areas in the country for total Hispanic population. Nearly 600,000 Hispanics reside in the area; they represent about 11 percent of metro residents, and over half of the almost million Hispanics in Georgia overall.

Mundo Hispanico, the largest Spanish-language weekly in Georgia — and across the Southern states — has expanded its distribution and operation to North Carolina, South Carolina, Alabama, and Florida. Formerly owned by Cox Communications, Mundo Hispanico has been shifting to digital, according to its editors.

The other Spanish-language publication, El Nuevo Georgia, has also been thriving, along with television stations Telemundo Atlanta and Univision 34.

Given the long history of African Americans in the South, the oldest media outlets in Atlanta are black newspapers. The Atlanta Daily World was founded in 1928 and The Atlanta Voice in 1956. Both played a significant role during the start of the Civil Rights Movement in the Deep South and continue to serve thousands of readers in the city today.

Despite some punitive, anti-immigration laws in Georgia, Teddy Dagwe, publisher of Dinq Magazine, a monthly that serves both the Christian and Muslim Ethiopian communities in metro Atlanta, says that immigrant communities continue to thrive in the area.

“We have each other here in big numbers. And it makes a difference when you have someone like Mayor Terry who understands us, who lives with us, and who listens to us,” Dagwe said.

Many see Clarkston and the greater Atlanta area as a bright spot in the national landscape — a place that has continued to welcome immigrants and refugees, where ethnic media and civic leaders are actively engaging with these communities to respond to their news and information needs.

Oni Advincula was a former editor and national media director for New America Media and a correspondent for The Jersey Journal. Currently, he works as a media consultant and and a freelance journalist. He is the co-author of “The State of Ethnic and Community Media in New Jersey” and has worked with ethnic media in 45 states for more than 20 years.

Centering Equity in Journalism during the 2020 Election — and Beyond

2020 was a marathon for journalists preparing for an election that seemed very likely to go off the rails. They did it while also facing unprecedented issues of safety, security, and stability in a global pandemic, a census year, and becoming increased targets for police violence. Journalists of color, Black journalists in particular, tackled all of the above while continuing to navigate systemic racism and leading a reckoning over racial justice in the industry.

In the lead-up to November and throughout election week, many of us were tuned into cable networks and refreshing news feeds around the clock, but national election coverage — predictably — failed us in many ways. As in past years, it often dealt in generalizations and erased identities. In one notable high-profile failure, CNN labeled Native Americans and presumably other unidentified voters as “something else,” rather than naming their demographics. Communities of color were also overwhelmingly targeted by misinformation.

But reporters and newsrooms around the country rose to the challenge of engaging communities, holding candidates accountable, and centering equity. If you’re a regular EJ Lab reader, it will come as no surprise that the best place to look for examples of equity-first election coverage is from newsrooms by and serving people of color. Here’s a snapshot of what these newsrooms did:

- They spoke directly to immigrant communities. Borderless Magazine, committed to more equitable immigration journalism, spoke with Rohingya Americans in Chicago about voting for the first time. Sahan Journal, dedicated to news for and about immigrants in Minnesota, reported about candidate engagement with Hmong American voters and the political diversity of their community.

- They reported information voters need. Bilingual El Tecolote published analysis by San Francisco State University students on how state propositions on the ballot would specifically impact California Latino communities. Native America Calling dug into the latest information about Native voting access for tribes across the country.

- They served their communities. Nonprofit start-up Pulso provided news, information, and perspectives to Latino voters who are often much more generalized by national media, such as how Latino voters shape candidate platforms, the significance of National Voter Registration Day, or the impact of new laws. For Spanish-language newsroom Enlace Latino NC, the story of voter education and registration didn’t end with the November election. They highlighted the impact of organizers in North Carolina whose work is ongoing.

- They exposed voter suppression. MLK50 told the story of how an ex-offender legally regained his voting rights despite major challenges in Tennessee. Sahan Journal covered how Muslim faith leaders pushed back against efforts to discourage Muslim voter turnout in Minnesota. The Lakota Times reported on state violations of the National Voter Registration Act in South Dakota.

- They sought out individual voter perspectives. Flint Beat wrote about the experience of being a 2020 Latinx voter in Michigan: including how discrimination, White House policies, and community organizing all have an impact on voter decisions. And The TRiiBE spoke with young Black Chicago voters about their ballot options and their hopes for future policy reforms.

The accomplishments above didn’t just happen by chance. They are the result of long-term commitment and relationship building between journalists of color and their communities, and they were fueled by funders who understood the urgency of 2020 and worked together to coordinate and drive resources to support capacity building, staffing, and targeted projects focused on serving communities. As we turn the corner into 2021, the urgency is still with us, and the need for more coordination, more resources and more commitment to journalists of color continues.

As we turn the corner into 2021, the urgency is still with us, and the need for more coordination, more resources and more commitment to journalists of color continues.

We have seen what we can do when we work together to drive support to these newsrooms — and it’s time to keep building momentum. Here’s what funders can do to support engaged, equitable reporting in 2021:

- Give more. Join the Racial Equity in Journalism Fund to deliver resources directly to newsrooms led by and serving communities of color. Many of the newsrooms mentioned above are grantees of the Fund.

- Make some noise. Use your communication channels to share examples of ongoing equity-first reporting. Newsrooms like The Atlanta Voice, Bridge Detroit and Wisconsin Watch, in places subject to widespread false claims of election fraud, are working around the clock to ensure ongoing accountability, and they need more support.

- Continue the work in 2021. The full story of the 2020 election — and the state of elections coverage — hasn’t yet been told. Pay attention to what worked and what didn’t. Tune in for learning and debriefs from projects like Election SOS who is analyzing how the Citizens Agenda, newsroom fellowships, Experts Network, Rapid Response Fund and other initiatives fueled more engaged, trusted, and representative election coverage.

For our part, the Engaged Journalism team at Democracy Fund will be identifying clear action steps to shift our internal structures and practices to put equity first in our grantmaking. Stay tuned for updates on how this goes in 2021.

Published with research support from Public Square Intern Areeba Shah.

Democracy Fund Statement on the University of North Carolina Board of Trustees Decision to Deny Tenure to Nikole Hannah-Jones

We call on the University of North Carolina Board of Trustees to reverse its decision to deny Nikole Hannah-Jones tenure. We have funded Hannah-Jones’s work at the Ida B. Wells Society, a project of UNC-Chapel Hill, since 2017.

Hannah-Jones’s critical reporting on racism and segregation in schools and housing is unimpeachable, and the 1619 Project for which she won a Pulitzer Prize, is a profound contribution to the discussion about American democracy. Over the course of her 20-year career as an investigative journalist, she has epitomized speaking truth to power, in the tradition of Ida B. Wells.

Hannah-Jones has earned her tenure position as the Knight Chair in Race and Investigative Journalism at the UNC Hussman School of Journalism and Media. To deny it to her is to lean into the culture of white supremacy that has plagued U.S. academic institutions for far too long. This decision highlights the very inequities that Hannah-Jones has dedicated her career to revealing.

We urge the University of North Carolina Board of Trustees to reverse their decision and immediately repair the harm that has been done.

Democracy Fund remains firmly committed to building more equitable journalism in North Carolina, where we have contributed nearly $3 million over the past five years to organizations in the state including the Ida B. Wells Society, the NC Local News Lab Fund, PressOn, and Free Press’s Charlotte News Voices.

When it’s Time to Learn Fast: How our Learning Processes Changed to Meet the Moment in the Summer of 2020

We tried something different. As a foundation, we are only as effective as our understanding of and alignment to what is occurring in the fields we fund. That’s tough to do in a complex environment. During a crisis, it’s even tougher. Try several crises.

In the summer of 2020, the grantees of our Digital Democracy Initiative (DDI) were revving up to combat a trifecta of mis- and disinformation about COVID-19, the Black Lives Matter movement, and the 2020 election. And we wanted to know how we could support them — not with slow, drawn-out information-gathering and analysis, but with something more agile.

We had to rethink the way we learn.

We didn’t have the luxury to wait for researchers to conduct a study and package it up for us to leisurely read nine months later. Nor did we want to ask our grantees to spare time that could be better used to do the work. So, we decided to approach our research and evaluation a little differently. We made a decision to minimize our plans for a developmental evaluation into a set of learning conversations that prioritized strengthening and facilitating information flows among our grantees over answering our own set of learning questions.

We also made a conscious decision to do something researchers would not advise (because of possible observer effects): we broke the fourth wall of objectivity. Our Associate Director of DDI and our Strategy and Learning Manager joined in on the focus groups facilitated by our evaluator. This had positive implications on our construction of knowledge. We were able to hear and respond to concerns in real time as our grantees were experiencing it and extract key points outside of those captured by our evaluators. Grantees were also able to learn from each other in real time and see other parts of the wider field they contribute to. While the resulting report, Responding to the Moment, synthesized much of this information, it was invaluable to have immediate access to it.

Our grantees expressed gratitude for the time to connect, particularly during the pandemic lockdown because some felt increasingly siloed. Hunkered down within the circles they were already in pre-pandemic, some felt it a challenge to do what the moment demanded: connect with new folks in order to advance the work.

We learned that one of the largest gaps in the mis- and disinformation network space existed between researchers and activists. While field-building and connecting across network gaps is a critical tactic for the Digital Democracy Initiative, this was an urgent learning for us. Leaning into making connections across fields of work is vital to successfully attacking the complex problem of mis- and disinformation. We have begun this through follow-up meetings and we are already seeing our grantees make these connections more explicitly in their work.

In our real-time learning, we made sure to center the experiences of people of color and women, with special attention to women of color who fall within both groups and experience unique circumstances because of this intersectionality. One important learning that resulted from this centering was the consequences and inequity of uniformed dollars in the philanthropic field due to “parachuting” and “trendiness.” As money was pouring into the mis- and disinformation space, dollars were going to new actors parachuting into the space for those resources as opposed to going to long-term actors who already worked on these issues. Additionally, a surface understanding of the challenges in the field made it likely that grantmakers would give their well-intentioned dollars to solutions that were trending, but not necessarily effective instead of buttressing effective efforts that activists and researchers were already cultivating. We have worked to elevate the voices and work of those who have been working in this space over time, and ensure funders understand the importance of that work as an anchor in this field.

These learnings underscore the inequitable ways that philanthropic support rarely goes into the hands of those most impacted by the problem and therefore best suited to address the problems. Centering the perspectives and experiences of those most negatively impacted by disinformation, people of color and women, allowed us to best understand our points of leverage for field solutions that are either out of the focus of or deprioritized by a broader philanthropic sector that is overwhelmingly wealthy and white.

The summer of 2020, like other crisis moments, was filled with chaos, trauma, and uncertainty. We were surprised by the learning that can happen even in the midst of crises when we strip away the formalities and reduce the amount of time and attention being taken away from important work being done in the field. Many of those crises continue today, and the changes we made to our learning will extend past the summer of 2020. We are thankful to our grantees for their time and honesty. The lessons we learned come from them.