Here at Democracy Fund, we’ve been focused on addressing our grantees’ shifting needs, and finding ways to support engaged journalism during the global coronavirus crisis. As this pandemic continues to impact our country’s most marginalized communities disproportionately, we’ve become more sure than ever that it’s crucial not only to fund journalism, but to fund equitable journalism.

What do we mean when we talk about equity?

The “E” in “DEI” — equity — is often overlooked when compared to diversity (bringing more voices to the table) and inclusion (making sure these voices are included and valued).

That’s because equity challenges us to see the need for change at a deep level — it calls for a shift in systems and structures to address inequality at the root.

We believe a just and equitable political system must eliminate structural barriers to ensure historically excluded communities have meaningful influence in our democracy.

At Democracy Fund, we are proud to be a systems change organization. We believe a just and equitable political system must eliminate structural barriers to ensure historically excluded communities have meaningful influence in our democracy. The same is true for all of our systems, but here on the Engaged Journalism Lab, we’re focused on what equity can look like — and how funders can support it — in journalism.

What is equity in journalism?

When we talk about equity in journalism, we mean:

- investing in newsrooms led by and serving historically marginalized groups;

- supporting organizations working to shift industry culture and leadership; and

- closing historic resource gaps that philanthropy has helped to perpetuate.

For news to be trusted and responsible, it must incorporate a diverse array of community voices, particularly those that have been ignored or harmed by storytelling and stereotyping in media. Only then will historically marginalized communities be able to count on news and support it as a vital civic asset. This means shifting resources, access, and leadership to, and embracing the power of these groups.

Funders can and should take the lead in supporting this work. That’s why, over the next year, the Engaged Journalism Lab will focus on engaging funders to support equity in journalism.

Why equity in journalism is critical

Last year, we published a series of reports looking at media by and for communities of color. The research revealed unique challenges among them, but the main concern for all was sustainability — simply having the dollars to keep the doors open.

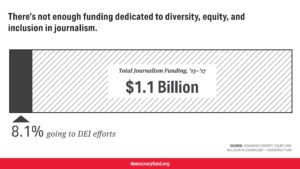

Unfortunately, these outlets are often overlooked by journalism funders. Our latest report, “Advancing Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion in Journalism: What Funders Can Do,” found that of the $1.1 billion journalism grants in the United States between 2013 and 2017, only 8.1 percent went to equity-focused efforts. This has deeply affected the stories that are told in this country.

We’ve sought to center equity throughout our Engaged Journalism strategy and across Democracy Fund’s Public Square Program. But we need exponentially more investment in this space if we’re going to correct historic inequities in philanthropic dollars. Here are three reasons why all journalism funders must invest in equity in journalism now:

1. It’s Good Business

America is rapidly diversifying, and newsrooms that want to remain relevant must learn how to serve all communities. As Martin Reynolds, co-Executive Director of the Maynard Institute, said at this year’s Knight Media Forum, “Let’s not say ‘voices from underrepresented communities.’ Let’s say ‘voices from your future audience.’”

A growing body of evidence shows a positive connection between the diversity of a company and its performance. For journalism, this means hiring and retaining reporters from different walks of life for more nuanced, creative reporting, and centering equity throughout senior management, who determine which stories are told and how.

2. It’s Good Ethics

Journalism’s equity problem has done significant damage. Color of Change’s 2017 report, “A Dangerous Distortion of Our Families,” examined representations of families, by race, in national and local media. It found that media disproportionately associated Black families with both poverty and criminality, stereotyping that has helped justify the historic over-policing of Black communities.

This biased reporting has existed for decades. In They Came to Toil, Dr. Melita Garza analyzes newspaper representations of Mexicans in the Great Depression, finding some of the same dehumanizing language being used today. This rhetoric has real-life consequences, from emboldening racist, anti-immigrant federal policies, to deadly violence against communities of color in places like Charleston and El Paso.

Let’s be clear: Journalists from historically marginalized communities should not be solely responsible for ensuring biases are checked in their respective newsrooms. All journalists should be aware of their biases and have the necessary tools at hand to recognize them in their reporting. There must be an equitable diversity of sources, stories, and staff which centers communities that have been harmed in the past.

3. It’s Good Journalism

What we’ve learned from supporting engaged journalism is that good reporting comes from deep listening. Listening not just to existing audiences, but to communities that haven’t been reached — particularly those that have been underserved by mainstream media.

News outlets must take into account the information needs of all communities, seek genuine input to determine those needs, and take time to develop trust. This investment in time and energy is critical, not only for serving communities more meaningfully, but also for producing the highest quality journalism.

What funders can do today to begin centering equity:

- Join the Racial Equity in Journalism Fund. This new joint fund supports news outlets led by and serving communities of color. They just announced their first round of grants, and you should see the important work they’re funding.

- Invest in organizations that support equity in journalism. Our Journalism DEI Tracker features over 70 groups that need more support in the work they are doing with newsrooms across the country. Our Journalism DEI Wheel shows different approaches to consider.

- Examine the inequitable practices within philanthropy that we must correct. Resources to get started include the National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy’s “Power Moves,” Equity in the Center’s “Awake to Woke to Work,” and Frontline Solutions’ “Equity Footprint.” We also highly recommend Edgar Villanueva’s book, Decolonizing Wealth (a great purchase to support your local independent bookstore right now).

Over the coming months, we’ll be sharing more resources, approaches and stories about equity in journalism. We invite you to join the conversation — follow us on Medium, or tweet us at @lmariahtrusty and @thedas.