According to the Pew Research Center, one in five Americans rely primarily on social media for their political news and information. This means a small handful of companies have enormous control over what a broad swath of America sees, reads, and hears. Now that the coronavirus has moved even more of our lives online, companies like Facebook, Google, and Twitter have more influence than ever before. And yet, we know remarkably little about how these social media platforms operate. We don’t know the answers to questions like:

- How does information flow across these networks?

- Who sees what and when?

- How do algorithms drive media consumption?

- How are political ads targeted?

- Why does hate and abuse proliferate?

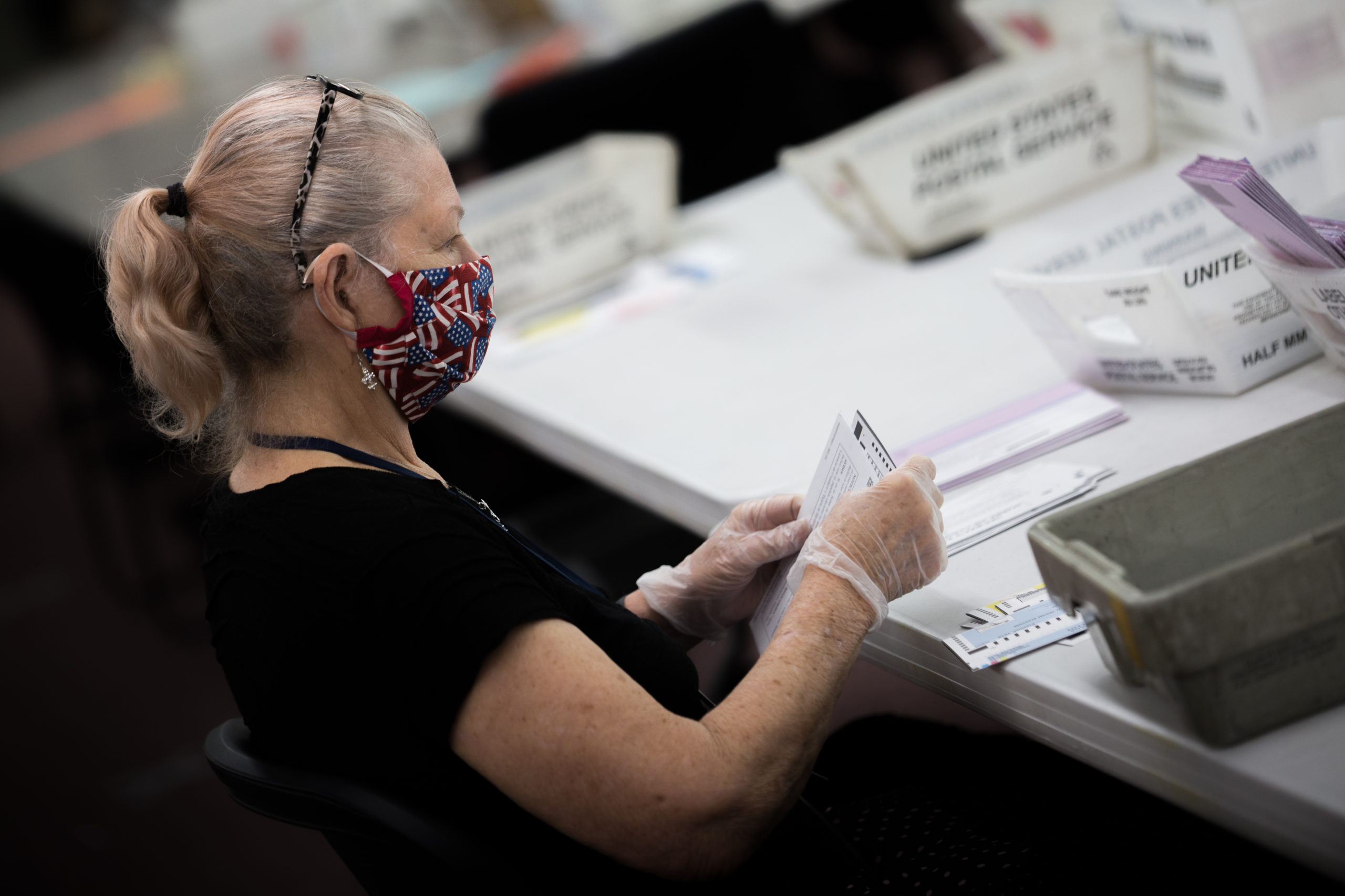

Without answers to questions like these, we can’t guard against digital voter suppression, coronavirus misinformation, and the rampant harassment of Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) online. That means we won’t be able to move closer to the open and just democracy we need.

A pattern of resisting oversight

The platforms have strong incentives to remain opaque to public scrutiny. Platforms profit from running ads — some of which are deeply offensive — and by keeping their algorithms secret and hiding data on where ads run they avoid accountability — circumventing advertiser complaints, user protests, and congressional inquiries. Without reliable information on how these massive platforms operate and how their technologies function, there can be no real accountability.

When complaints are raised, the companies frequently deny or make changes behind the scenes. Even when platforms admit something has gone wrong, they claim to fix problems without explaining how, which makes it impossible to verify the effectiveness of the “fix.” Moreover, these fixes are often just small changes that only paper over fundamental problems, while leaving the larger structural flaws intact. This trend has been particularly harmful for BIPOC who already face significant barriers to participation in the public square.

Another way platforms avoid accountability is via legal mechanisms like non-disclosure agreements (NDAs) and intellectual property law, including trade secrets, patents, and copyright protections. This allows platforms to keep their algorithms secret, even when those algorithms dictate social outcomes protected under civil rights law.

Platforms have responded to pressure to release data in the past — but the results have fallen far short of what they promised. Following the 2016 election, both Twitter and Facebook announced projects intended to release vast amounts of new data about their operations to researchers. The idea was to provide a higher level of transparency and understanding about the role of these platforms in that election. However, in nearly every case, those transparency efforts languished because the platforms did not release the data they had committed they would provide. Facebook’s reticence to divulge data almost a year after announcing the partnership with the Social Science Research Council is just one example of this type of foot-dragging.

The platforms’ paltry transparency track record demonstrates their failure to self-regulate in the public interest and reinforces the need for active and engaged external watchdogs who can provide oversight.

How watchdog researchers and journalists have persisted despite the obstacles

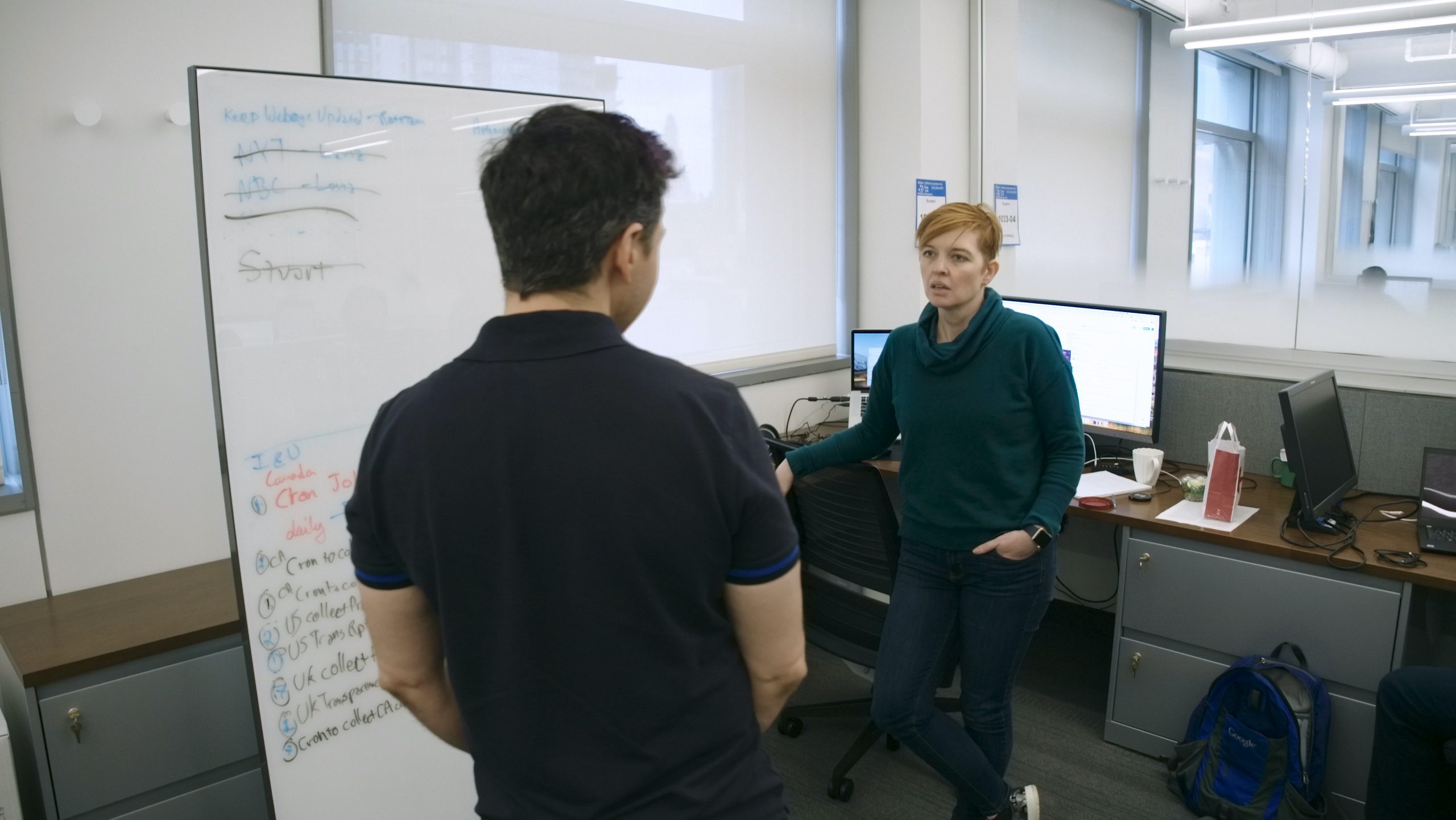

Without meaningful access to data from the platforms, researchers and journalists have had to reverse engineer experiments that can test how platforms operate and develop elaborate efforts merely to collect their own data about platforms.

Tools like those developed by NYU’s Online Political Transparency Project have become essential. While Facebook created a clearinghouse that was promoted as a tool that would serve as a compendium of all the political ads being posted to the social media platform, NYU’s tool has helped researchers independently verify the accuracy and comprehensiveness of Facebook’s archive and spot issues and gaps. As we head into the 2020 election, researchers continue to push for data, as they raise the alarm about significant amounts of mis/disinformation spread through manipulative political groups, advertisers, and media websites.

Watchdog journalists are also hard at work. In 2016, the Wall Street Journal built a side-by-side Facebook feed to examine how liberals and conservatives experience news and information on the platform differently. Journalists with The Markup have been probing Google’s search and email algorithms. ProPublica has been tracking discriminatory advertising practices on Facebook.

Because of efforts like these, we have seen some movement. The recent House Judiciary Committee’s antitrust subcommittee hearing with CEOs from Apple, Facebook, Google and Amazon was evidence of a bipartisan desire to better understand how the human choices and technological code that shape these platforms also shape society. However, the harms these companies and others have caused are not limited to economics and market power alone.

How we’re taking action

At Democracy Fund, we are currently pushing for greater platform transparency and working to protect against the harms of digital voter suppression, coronavirus misinformation, and harassment of BIPOC by:

- Funding independent efforts to generate data and research that provides insight regarding the platforms’ algorithms and decision making;

- Supporting efforts to protect journalists and researchers in their work to uncover platform harms;

- Demanding that platforms provide increased transparency on how their algorithms work and the processes they have in place to prevent human rights and civil rights abuses; and

- Supporting advocates involved in campaigns that highlight harms and pressure the companies to change, such as Change the Terms and Stop Hate for Profit.

Demanding transparency and oversight have a strong historical precedent in American media. Having this level of transparency makes a huge difference for Americans — and for our democracy. Political ad files from radio and television broadcasters (which have been available to the public since the 1920s) have been invaluable to journalists reporting on the role of money in elections. They have fueled important research about how broadcasters work to meet community information needs.

The public interest policies in broadcasting have been key to communities of color who have used them to challenge broadcaster licenses at the Federal Communications Commission when they aren’t living up to their commitments. None of these systems are perfect, as many community advocates will tell you, but even this limited combination of transparency and media oversight doesn’t exist on social media platforms.

Tech platforms should make all their ads available in a public archive. They should be required to make continually-updated, timely information available in machine-readable formats via an API or similar means. They should consult public interest experts on standards for the information they disclose, including standardized names and formats, unique IDs, and other elements that make the data accessible for researchers.

Bottomline, we need new policy frameworks to enforce transparency, to give teeth to oversight, and to ensure social media can enable and enhance our democracy. Without it, the open and just democracy we all deserve is at real risk.