- Table of Contents

- Main Takeaways

- Introduction

- Views of Racial Inequality and Discrimination

- Changing Messages About Race

- Views of Immigration

- The Evolution of Immigration Politics

- Conclusion

- Download the Report

ABOUT DEMOCRACY FUND

Created by eBay founder and philanthropist Pierre Omidyar, Democracy Fund is an independent and nonpartisan foundation that confronts deep-rooted challenges in American democracy while defending against new threats. Democracy Fund has invested more than $275 million in support of those working to strengthen our democracy through the pursuit of a vibrant and diverse public square, free and fair elections, effective and accountable government, and a just and inclusive society. For more information, please visit www.democracyfund.org.

ABOUT THE VOTER SURVEY

The Views of the Electorate Research (VOTER) Survey is a longitudinal survey that Democracy Fund has conducted in partnership with YouGov since December 2016. This report is based on data that include the latest wave of the VOTER Survey, which surveyed 6,000 adults (age 18 and up) online from February 22 to March 15, 2024. The VOTER Survey is distinct because it draws from a longstanding panel of voters who have been interviewed periodically since it was launched by YouGov in December 2011, including after the 2012, 2016, 2018, 2020, and 2022 elections, with thousands of respondents repeatedly participating since 2011.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

John Sides is William R. Kenan, Jr. Professor of Political Science at Vanderbilt University. He studies political behavior in American and comparative politics. He is an author of The Bitter End: The 2020 Presidential Campaign and the Challenge to American Democracy as well as books on the 2012 and 2016 elections.

Michael Tesler is a professor of political science at University of California Irvine. He is author of Post-Racial or Most Racial? Race and Politics in the Obama Era, coauthor of Obama’s Race: The 2008 Election and the Dream of a Post-Racial America, and coauthor of Identity Crisis: The 2016 Presidential Campaign and the Battle for the Meaning of America.

Robert Griffin is the Associate Director of Research at Democracy Fund. Prior, Griffin was the Research Director for the Democracy Fund Voter Study Group, the Associate Director of Research at the Public Religion Research Institute and the Director of Quantitative Analysis at the Center for American Progress.

Main Takeaways

- Between 2011 and 2020 there was dramatic shift in attitudes on racial inequality and discrimination as well as immigration. The attitudes of Democrats and independents became notably more liberal during this period.

- Since 2020, attitudes on racial inequality and discrimination have been relatively stable. Any changes mostly reflect modest declines in liberal attitudes among Democrats and modest increases in these attitudes among Republicans. The parties are a bit less polarized in 2024 than in 2020.

- The initial changes in attitudes about racial inequality and discrimination resulted from Trump’s polarizing presidency and the salience of racial justice issues, especially after George Floyd’s murder. The trends since 2021 stem from declining media attention to racial justice issues and thus less priority on these issues among voters. Polling also shows that Biden is a less racially polarizing figure than Trump.

- On immigration, there has been a rightward shift in both parties and especially among Republicans. This reflects the increasing media attention to immigration and the public salience of the issue, particularly for Republicans. Moreover, the bipartisan elite consensus on the need for more border security has helped produce parallel shifts among Republican and Democrats.

- Taken together, these trends suggest that race and immigration might have a new “thermostatic” dynamic, with attitudes shifting in the opposite direction of the party in the White House.

Introduction

As president, Donald Trump’s political agenda and rhetoric often centered on polarizing ideas about civil rights, crime, and immigration. He referred to immigrants coming from “shithole countries,” defended Confederate statues, and pursued controversial policies such as separating immigrant children from their families when they were detained crossing the U.S.-Mexico border.

When Joe Biden took office in January 2021, he seemed poised to change the subject. His agenda was more centered on other priorities, such as the economic recovery from the pandemic. But Biden also inherited party coalitions that increasingly differ in their views of racial equality, immigration, and related issues. He talked about these issues very early in his presidency and reversed some of Trump’s policies.1 However, his desire to chart a different course on immigration faced significant challenges, as record numbers of immigrants entered the U.S. from Mexico. In a January 2024 statement, he called the situation at the border “broken.”2

In this report, we investigate how Americans’ attitudes about race and immigration evolved over Trump’s presidency and in the first three years of Biden’s term. We draw on several different surveys, but especially the Democracy Fund VOTER Survey (Views of the Electorate Research Survey), which has interviewed a sample of Americans multiple times since late 2011, augmenting that sample with new respondents along the way. The most recent survey is from March 2024. Together, the VOTER Survey and other surveys help us identify trends in these attitudes.

We find that views of racial inequality and discrimination changed dramatically under Trump, with Democrats in particular becoming more likely to take the “liberal” view, which attributes racial inequality to structural forces as opposed to individuals’ own failings. After Trump’s departure, those attitudes have remained relatively stable. There have been very modest declines in liberal attitudes among Democrats and an even more modest increase in liberal attitudes among Republicans. Other surveys and survey questions show a similar pattern. Thus, Democratic and Republican attitudes have converged slightly after several years of divergence.

We argue that the trends from 2016 to 2020 reflect the polarizing effect of Trump, particularly in driving Democrats to the left, combined with the renewed salience of racial justice issues after the murder of George Floyd. Beginning in the fall of 2020, racial justice issues faded from the news as the protests abated. As of 2024, voters see these issues as less important than they did four years ago. Moreover, Biden has emerged as a president who is less polarizing on these issues. These factors may have helped create this slight convergence between the parties.

The story of immigration attitudes is different. There was the same leftward shift under Trump, again mostly among Democrats. But under Biden, several measures of these attitudes show a rightward shift — with less support for a pathway to citizenship for undocumented immigrants and more support for decreasing immigration, deporting undocumented immigrants, and building a U.S.-Mexico border wall. Some of these measures show roughly similar shifts among Democrats and Republicans, and others show a much larger shift among Republicans.

We attribute these trends to two factors. One is the increase in border crossings and the resulting increase in the salience of the issue. Immigration has become more important in news coverage and in voters’ minds even as racial equality has become less important. The other is, once again, the elite leadership of public opinion. In particular, under Biden there has been some degree of elite bipartisan consensus on the need for increased border security, which may have helped move both Democratic and Republican voters in a conservative direction.

Taken together, these trends in opinions and their likely causes complicate the common narrative that the country experienced a “Great Awokening” followed by a decline from what commentators have called “peak wokeness.” The likelier story — and the more probable future for American politics — is that issues like race and immigration have become “thermostatic,” with public opinion moving against the president’s rhetoric, priorities, and policies. Thus, we should expect opinions about these issues to shift in different ideological directions in response to events, policy, and elite rhetoric, rather than rising to a single liberal peak and then falling.

The reason to expect thermostatic politics is that the two parties continue to differ on why racial inequality arises, whether racial discrimination is a problem, and how to approach both legal and undocumented immigration. Democrats and Republicans are still significantly more polarized than they were before Trump became president. Thus, we should expect Democratic and Republican administrations to govern differently on these issues, pushing policy in their preferred direction, even as some Americans move in the opposite direction.

Views of Racial Inequality and Discrimination

To measure views of racial inequality and discrimination, we focus on three main topics. The first is how citizens explain racial inequalities involving Black Americans, and specifically whether they attribute it more to structural forces or to the individual characteristics of Black people. The second is how much discrimination citizens believe that different racial and ethnic groups face. The third is how much different racial and ethnic groups are advantaged or disadvantaged because of their race.

These topics that speak to whether Americans even see patterns of racial discrimination and disadvantage to begin with, which groups they believe are most affected, and what they believe creates any disadvantages.

To measure attributions about racial inequality, we draw on a long-standing battery of questions that ask respondents whether they agree or disagree with the following four statements:

- Over the past few years, Black people have gotten less than they deserve.

- Irish, Italian, Jewish, and many other minorities overcame prejudice and worked their way up. Black people should do the same without any special favors.

- It’s really a matter of some people not trying hard enough; if Black people would only try harder they could be just as well off as white people.

- Generations of slavery and discrimination have created conditions that make it difficult for Black people to work their way out of the lower class.3

As we and others have documented, there were substantial changes in these attitudes between 2011 and 2020, as Democrats and independents became more likely to attribute racial inequality to structural rather than individual-level factors. These trends are almost entirely due to partisans updating their attitudes about race, not to people changing their partisanship.4 Other research has demonstrated that these changes were genuine and not due to survey respondents’ cloaking their real feelings behind socially desirable responses.5

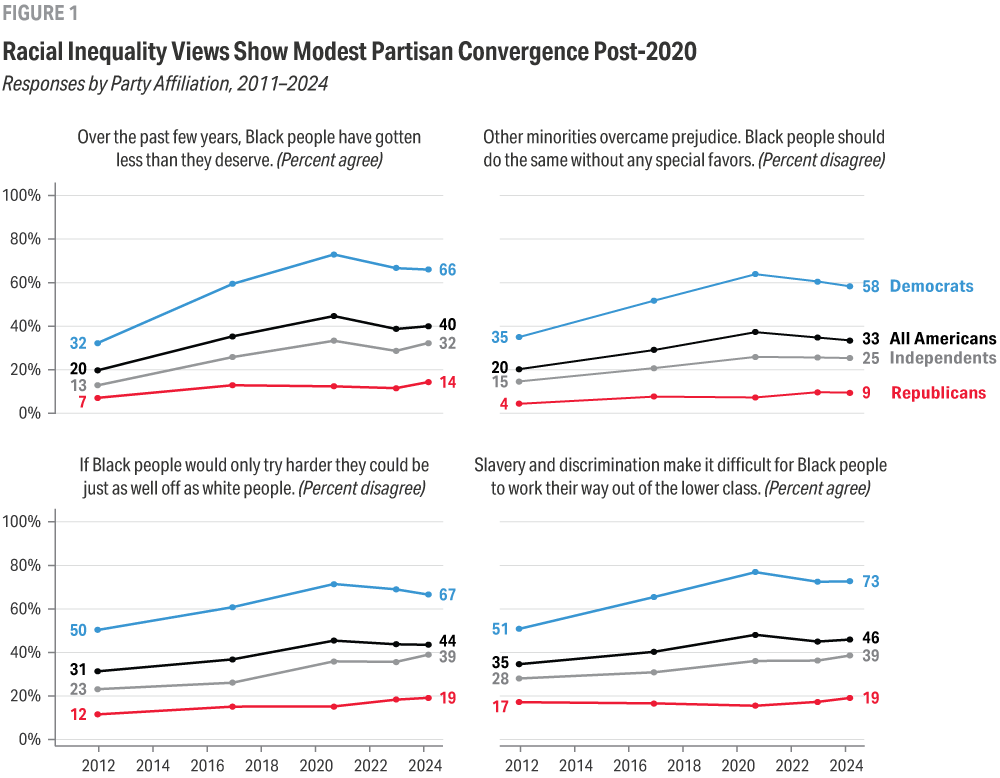

In the 2022 and 2024 VOTER Surveys, overall opinion was similar to what it was after the 2020 election (Figure 1). The number of Americans who disagreed that Black people should overcome prejudice without special favors was 37 percent in the November 2020 survey and 33 percent in March 2024. The fraction of Americans who disagreed that Black people could be just as well off as white people was 45 percent in 2020 and 44 percent in 2024. A similar fraction agreed that generations of discrimination and slavery still prevent Black people from making economic progress, and this fraction also remained relatively stable between 2020 and 2024. There was a small drop in the percentage of Americans who agreed that Black people have gotten less than they deserve — from 45 percent in 2020 to 40 percent in 2024.

The overall stability in these attitudes conceals a modest partisan convergence. In 2024, a slightly higher percentage of Republicans expressed more liberal attitudes on these indicators, although most Republicans did not. Meanwhile, liberal attitudes became a little bit less prevalent among Democrats. For example, relative to 2020, fewer Democrats in 2024 agreed that Black people have gotten less than they deserve (a drop from 73 percent to 66 percent) and agreed that slavery and discrimination have prevented Black people from making economic progress (a drop from 77 percent to 73 percent).

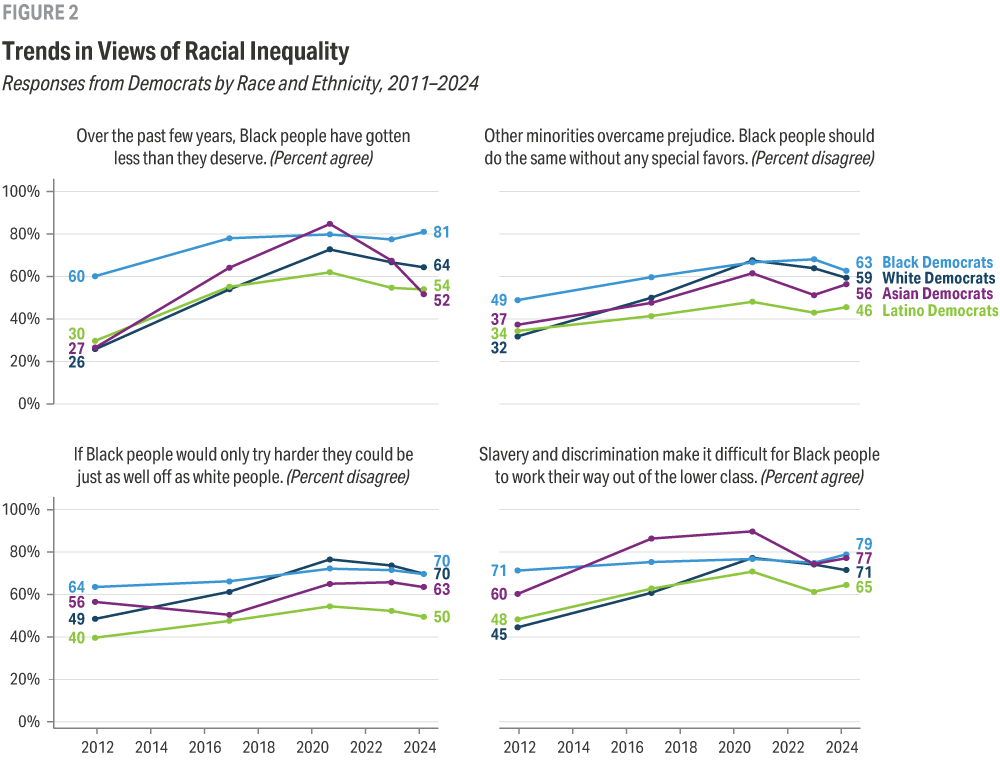

These changes occurred mainly among white, Latino, and Asian Democrats (Figure 2).6 Notably, even with these recent shifts, Democrats in all major racial and ethnic groups are still more likely than they were 10 years ago to give responses consistent with structural explanations for racial inequality. And on most indicators, white, Latino, and Asian Democrats have attitudes more similar to those of Black Democrats than they did in late 2011.

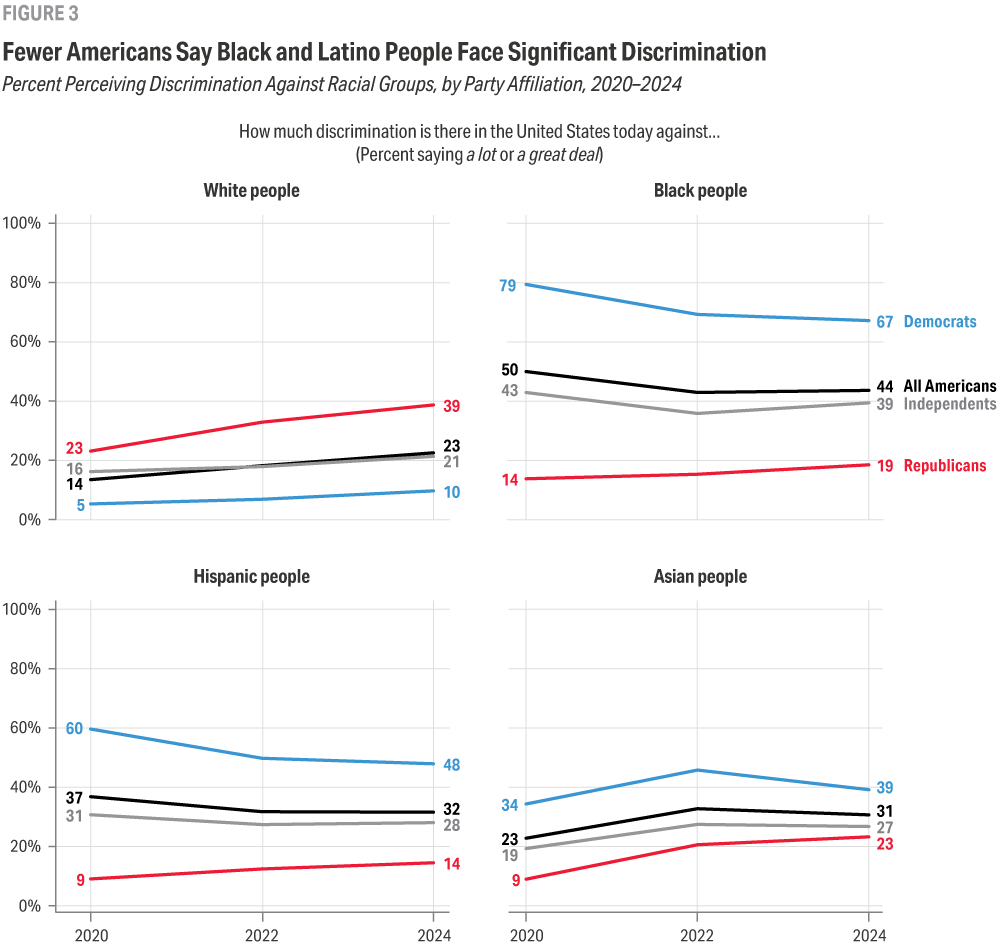

The VOTER Survey has also tracked Americans’ perceptions of discrimination over a shorter timespan (2020, 2022, and 2024) — specifically, how much discrimination people believe a given racial or ethnic group is experiencing. Overall, fewer Americans now say that Black and Latino people face high levels of discrimination (Figure 3). The fraction saying that Black people face “a lot” or “a great deal” of discrimination declined from 50 percent in September 2020 to 44 percent in March 2024. In addition, fewer Americans say that Latino people face high levels of discrimination (a shift from 37 percent to 32 percent). By contrast, the number of Americans who said that Asian people face discrimination increased from 23 percent to 31 percent.

In the first two cases, these drops were driven mainly by shifts among Democrats and independents. Between 2020 and 2024, there was a 12-point drop in the percentage of Democrats who said Black people face high levels of discrimination.7 There was a 4-point drop among independents. If anything, Republicans became slightly more likely to say that Black, Latino, and Asian people faced serious discrimination. As a result, there is less party polarization in perceptions of discrimination against these groups in 2024 than in the two prior surveys.

However, perceptions of discrimination against white people showed a different pattern: There was an increase in perceptions of discrimination — but mostly among Republicans. The fraction of Republicans who said that white people faced high levels of discrimination increased from 23 percent to 39 percent. In contrast to other trends identified in this section, this created more polarization between the parties, not less.

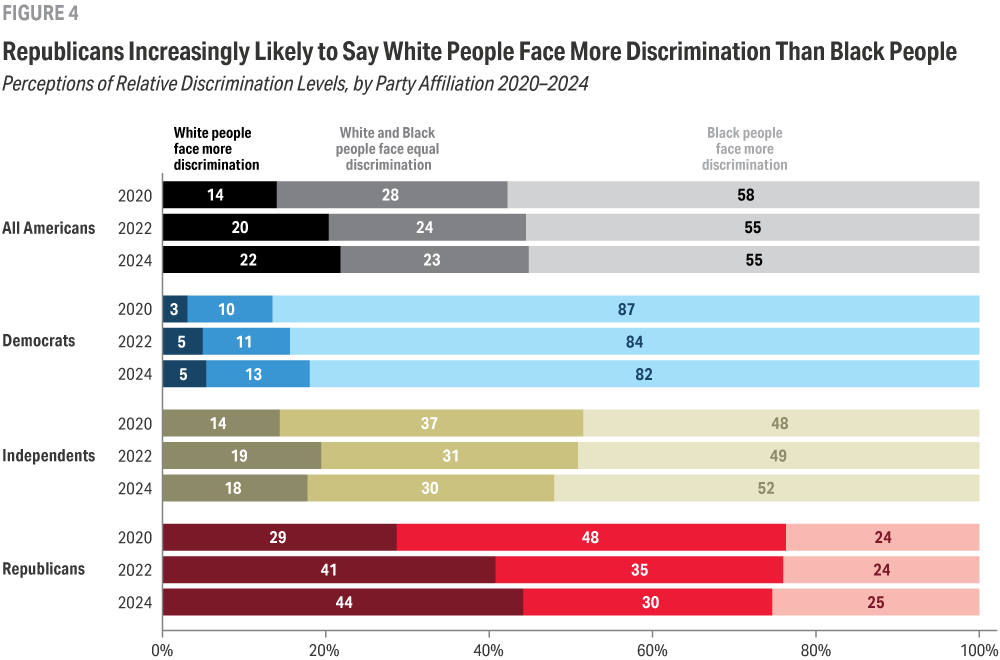

There was also an increase in the percentage of Republicans who appeared to believe that white people face more discrimination than do Black people or Latino people (Figure 4). For example, 29 percent of Republicans said that white people faced more discrimination than Black people in 2020. By 2024, that increased to 44 percent. Fewer Republicans (25 percent) said that Black people experience more discrimination. By comparison, in 2024 the vast majority of Democrats (82 percent) said that Black people experience more discrimination. The trends for beliefs about white and Latino discrimination are nearly identical among all Americans and partisan groups over this time period.

This fits a general pattern: Democrats tend to believe that historically marginalized groups — such as Black people, women, Jewish people, and Muslim people — experience more discrimination than historically advantaged groups such as white people, men, and Christians. Republicans tend to see these groups as facing similar levels of discrimination or, as the example above illustrates, that the historically advantaged groups actually face more discrimination.8

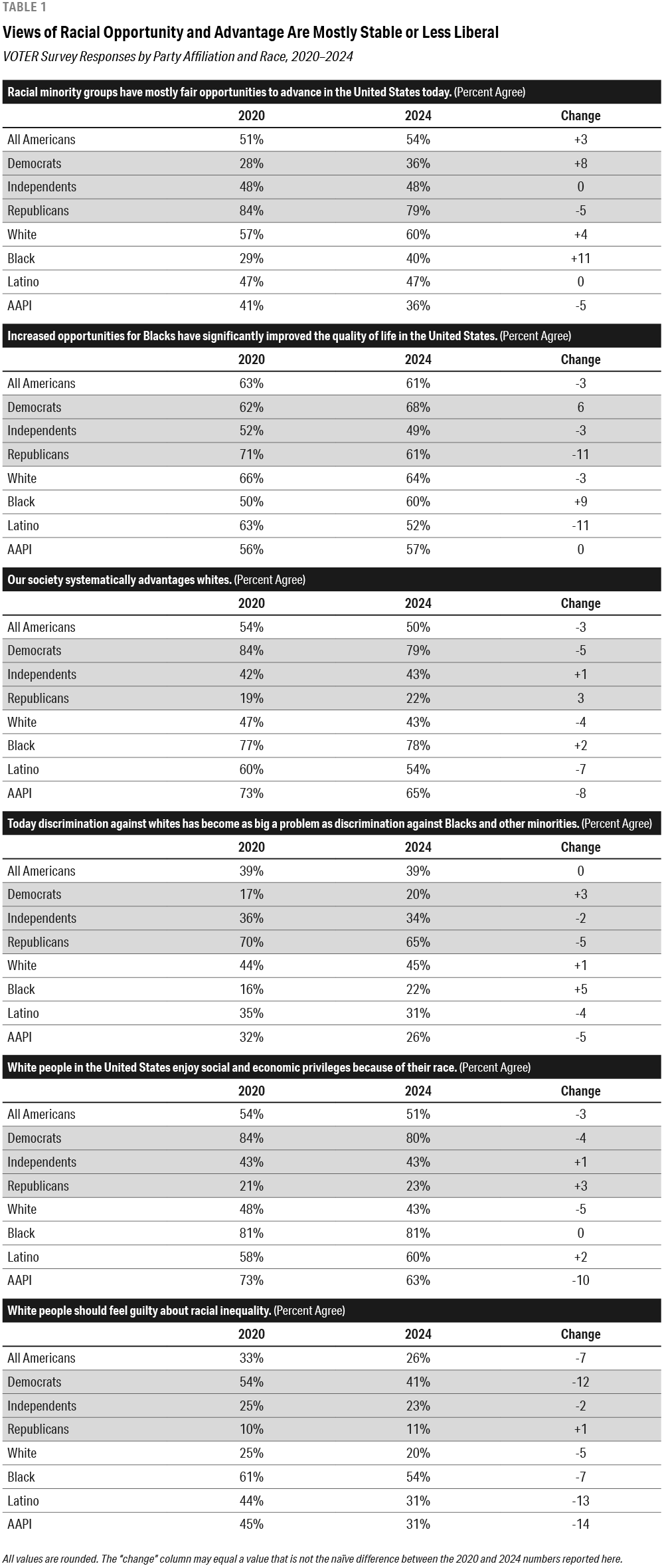

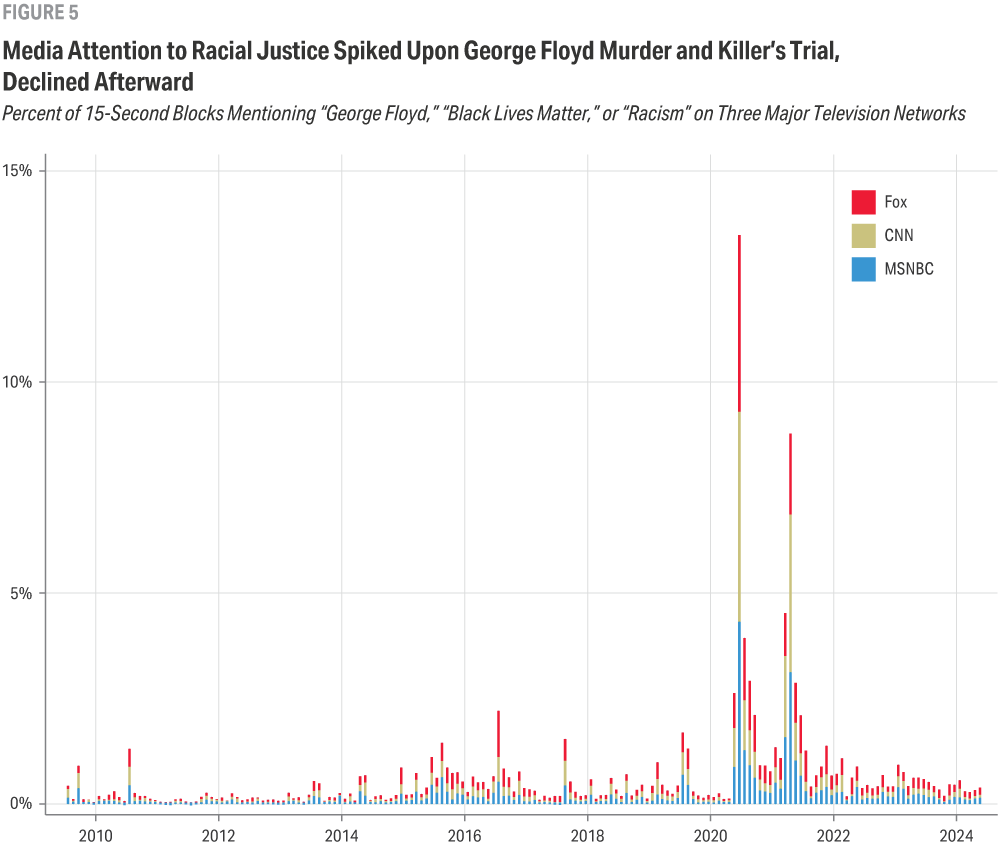

The VOTER Survey also included several questions relating to perceptions of racial opportunities and advantages. These were asked in 2020, 2022, and 2024. Similar to the trends shown in Figures 1 and 2, there has been stability in these attitudes and signs that attitudes are a bit less liberal than they were two years ago (Table 1).

In 2020 and 2024, the same fraction of Americans (51 percent) said that racial minority groups have mostly fair opportunities to advance. There were some small shifts in other indicators, ranging from 0 to 7 percentage points, with any changes moving in the same direction: Fewer Americans agreed that society systematically advantages white people (54 percent vs. 50 percent) or, phrased differently, that white people enjoy social and economic privileges because of their race (54 percent vs. 50 percent). Americans were also less likely to agree that white people should feel guilty about racial inequality (33 percent vs. 26 percent) or that increased opportunities for Black people have improved the country’s quality of life (63 percent vs. 58 percent).

On several of these questions, the partisan gaps, although still substantial, were slightly smaller in 2024 than in 2020, mirroring the modest convergence evident in Figures 1 and 3. But Democrats and Republicans remain far apart.

Similar findings emerged in the Cooperative Election Study, a different survey that was also conducted in 2020 and 2022 (Table 2). In response to questions about whether white people have an advantage and whether racial problems are rare, there were also small shifts. More often than not, any shifts meant that slightly fewer Americans expressed concern about white advantage or racial problems. There were, likewise, parallel trends among most racial groups and modest convergence between Democrats and Republicans.

At the same time, large differences between Democrats and Republicans remain. For example, in 2022, 84 percent of Democrats but only 20 percent of Republicans agreed that white people had advantages because of the color of their skin.

The Cooperative Election Study also asked three questions only of respondents who did not identify as white. These questions asked about white people’s views of racial discrimination and racial advantages. In both years, majorities or near-majorities of Black, Latino, and Asian-American respondents expressed resentment about white people’s denial of racial discrimination, agreed that white people get away with offenses that Black people cannot, and agreed that white people do not try hard to understand the problems Black people face. Unsurprisingly, these sentiments were particularly prevalent among Black respondents. But, in line with the trends in Table 1, such sentiments were a bit less prevalent in 2022 than 2020 — and this was true among all three of these racial groups.

Changing Messages About Race

What accounts for these trends in attitudes about racial inequality and discrimination? Any answer to this question must help explain both the growing partisan differences under Trump, largely driven by Democratic voters moving in a racially progressive direction, and the modest shifts under Biden’s presidency, which reflect less progressive views among Democratic voters and more progressive views among Republican voters. It is a pattern of rapid partisan divergence followed by a small convergence.

These trends derive from a profound change in the messages that voters heard from political leaders and activists. Between 2015 and 2020, voters encountered Trump’s hostile statements about racial and ethnic minorities as well as a highly visible social movement pushing for racial justice after the murder of George Floyd — a movement that Trump attacked vociferously. But the public presence of this movement faded in late 2020, and Trump then lost to Biden, who has not been as polarizing a figure on issues related to race.

Starting in 2015 during his presidential campaign and then continuing during his presidency, Trump’s rhetoric had the counterintuitive effect of pushing public opinion about racial inequality and discrimination to the left, especially among Democrats. Trump’s positions and statements on race, immigration, and Muslims created an incongruity for Democrats who disliked Trump but were otherwise more moderate or conservative on these issues.9 The easiest way for those Democrats to resolve this incongruity was to shift their positions away from Trump’s — a phenomenon that is common for people who find themselves in the uncomfortable position of having previously supported some of the opposing party’s mostly salient policies.10

And that is precisely what Democrats did. White Americans’ feelings about Trump in 2016 were strongly associated with subsequent changes in their views of racial inequality as well as their feelings about the Black Lives Matter movement and police. In particular, the less favorably white Americans felt toward Trump in 2016, the more their attitudes shifted in a liberal direction between 2016 and 2020.

This divergence between Democrats and Republicans was only magnified during the racial justice protests after George Floyd was murdered on May 25, 2020. Initially, Americans of all partisan persuasions shifted toward a more sympathetic view of Black Americans and a less favorable view of the police. But those effects waned as the protests moved out of the news. By early 2021, any impact of these protests was visible mainly among Democrats, pushing them toward a more progressive view. As a result, Democrats and Republicans ended up further apart than they were before the protests.11

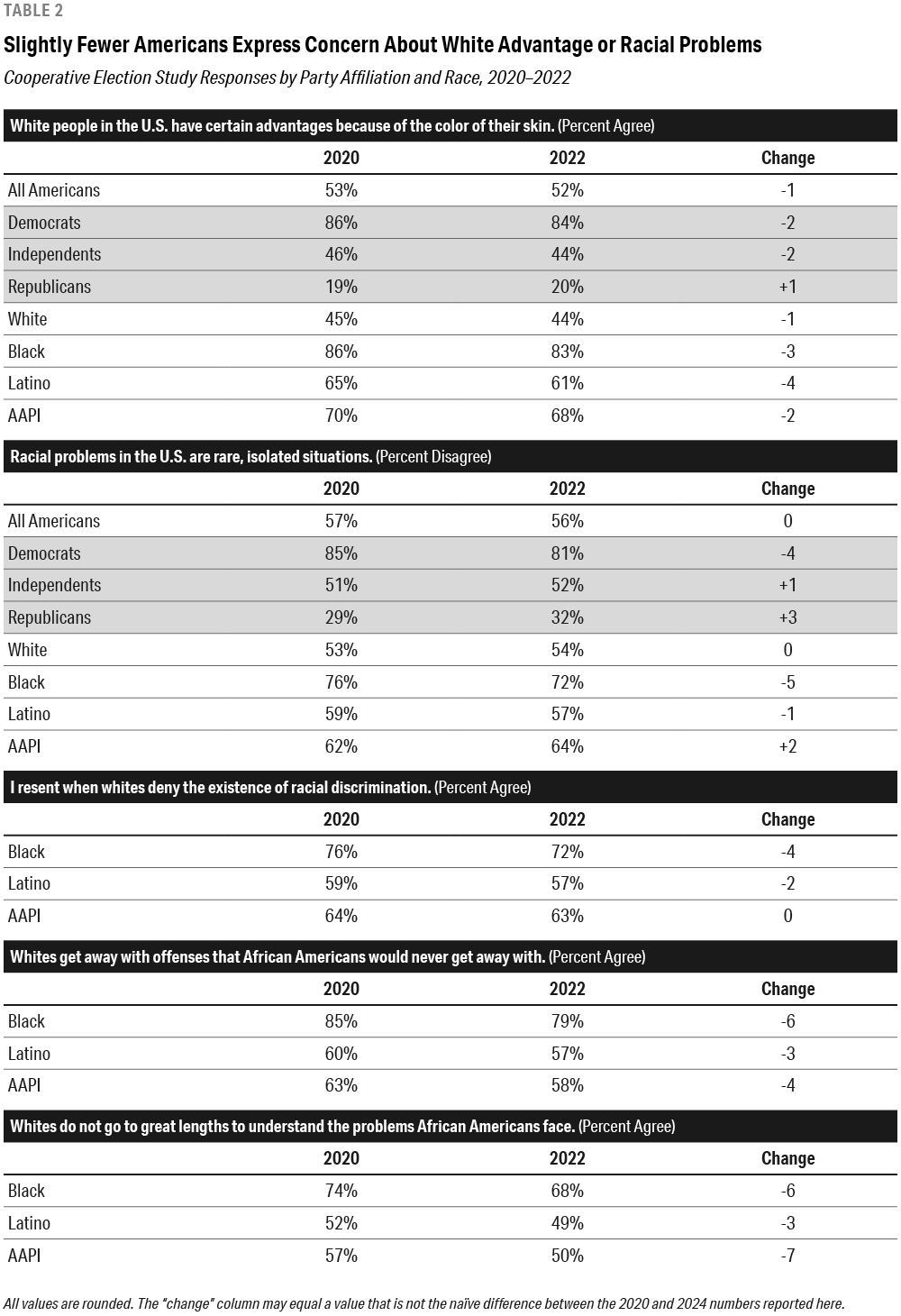

This began to change in 2021. Without a prominent mobilization around racial justice, the topics that were frequently in the news after Floyd’s murder — references to Floyd himself, to Black Lives Matter, to racism — never returned to their peak during the summer of 2020 except for a temporary spike when Floyd’s killer, Derek Chauvin, was convicted in April 2021 (Figure 5).12

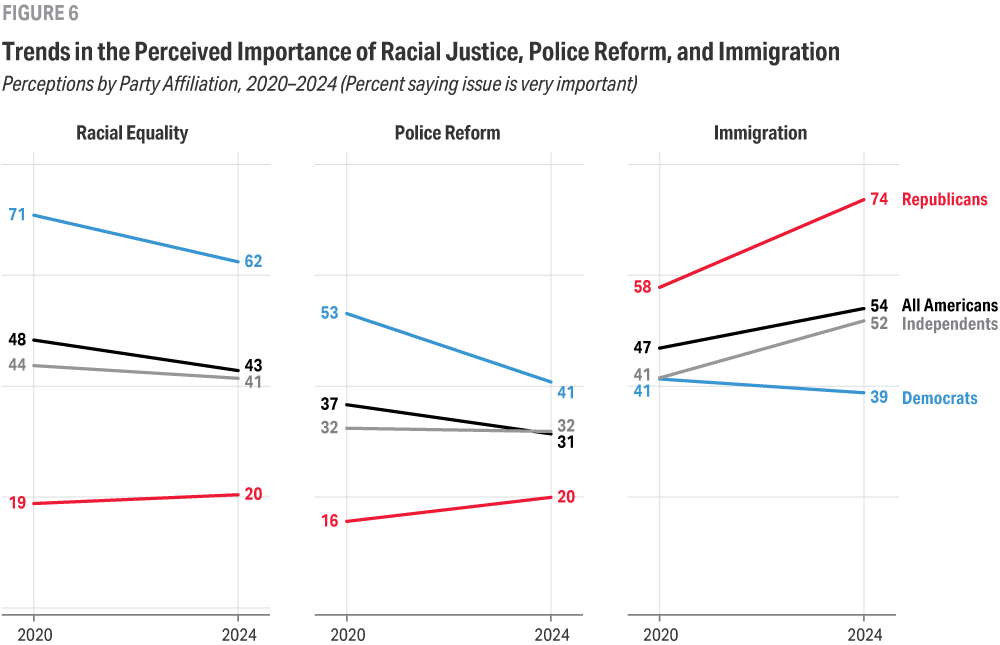

Alongside this decline in news attention, fewer voters perceived racial equality and police reform as important issues (Figure 6).13 In the 2024 VOTER Survey, 43 percent of respondents said racial equality was a very important issue, down from 48 percent in 2020. This decrease occurred mostly among Democrats (9-point drop) and independents (3-point drop). The importance of police reform dropped as well.14 In both cases, these declines among Democrats were evident in every major racial and ethnic group.

The change brought about by Biden’s victory also shaped the messages voters encountered. With Trump out of office, the backlash against his presidency became less of a factor in public opinion about racial inequality and discrimination than it was back in 2020. This helps to explain why Democratic views have become a little bit less liberal.15

Biden himself has also been a less polarizing figure on these issues. He did not embrace the most progressive positions in his party after Floyd’s murder, rejecting calls to “defund the police.” And although his administration’s policymaking represents a clear departure from Trump’s, Americans do not perceive Biden as favoring one racial group over another to the extent that they did Trump when he was president.

For example, nearly half (49 percent) of respondents in the September 2020 VOTER Survey said that the Trump administration favored white people over Black people. At that point, almost no one said his presidency favored Black people over white people. In the November 2022 VOTER survey, conducted almost two years into Biden’s presidency, just 27 percent of Americans thought Biden favored Black people over white people while 10 percent thought the opposite. Overall, Americans perceived less racial favoritism from Biden than they did from Trump.

More recent polling shows the same difference in perceptions. An October 30–November 3, 2023, CBS News poll asked “If Donald Trump wins in 2024, do you think his policies in a second term would try to put the interests of white people over racial minorities, racial minorities over white people, or treat their interests the same way?” Almost half (48 percent) said “white people over minorities,” and only 3 percent said “racial minorities over white people.” When asked the same question about Biden, 39 percent said “racial minorities over white people” and 18 percent said “white people over racial minorities.”16

Perceptions of racial favoritism are also less polarized by party when Americans think about Biden compared to Trump. When this 2023 CBS News poll asked about Trump, 80 percent of Democrats said he would favor white people, while only 14 percent of Republicans thought that. Almost all Republicans (82 percent) said Trump would treat white people and racial minorities the same way.

When asked about Biden, Democrats and Republicans were divided, but not as starkly. Among Democrats, 67 percent said Biden would treat white people and racial minorities the same way, while 20 percent said he would favor white people and 13% said he would favor racial minorities. Most Republicans (63 percent) said Biden would favor racial minorities but over a third said white people (17 percent) or both groups equally (20 percent).

Thus, Biden’s policymaking and rhetoric on issues related to race have not inspired the same polarized perceptions as Trump’s. This may have helped create the modest partisan convergence in racial attitudes between 2020–24.

Views of Immigration

Trends in attitudes about immigration are similar to trends in attitudes about racial inequality and discrimination in some respects, but there are also important differences. There were increasingly liberal immigration attitudes during the Trump presidency — driven in large part by shifts among Democrats. These attitudes have also shifted in the conservative direction since 2020.

But unlike with attitudes about racial inequality and discrimination, this conservative shift is visible in both parties and especially among Republicans. Thus, the modest partisan convergence in racial attitudes does not necessarily emerge in immigration attitudes: Both parties are moving in the same direction, and the larger shift among Republicans on certain survey questions has created even more polarization.

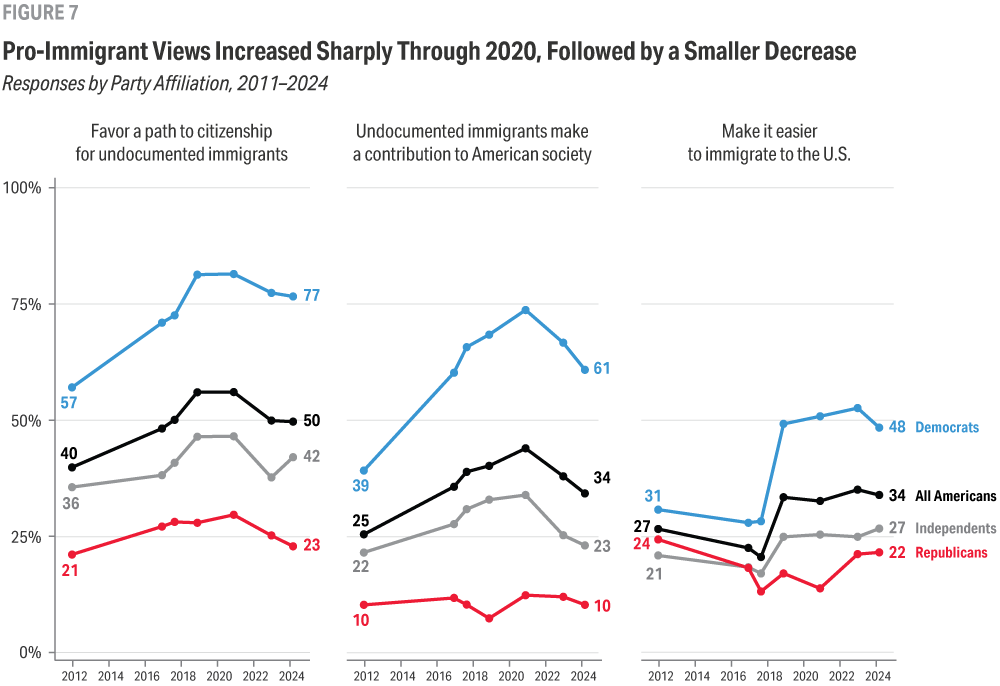

The VOTER Survey has asked three questions consistently since late 2011: whether to create a path to citizenship for undocumented immigrants, whether undocumented immigrants contribute to society or are a drain on society, and whether it should be easier or harder to immigrate to the U.S. The first two of those questions show trends similar to the trends in attitudes about racial inequality and discrimination: a sharp increase in pro-immigrant views through 2020, particularly among Democrats, and then a smaller decrease in those views between 2020 and 2024 (Figure 7). The question about making it easier or harder to immigrate shows the same increase among Democrats during the Trump administration, but a smaller decrease afterward. Interestingly, the percentage of Republicans who wanted to make it easier to immigrate actually increased by 8 points between 2020 and 2024.

But other survey questions show a somewhat different pattern, with sharper conservative shifts among Republicans than Democrats. This may reflect the fact that Republican attitudes are already quite conservative on the three immigration questions in the VOTER Survey; simply put, there is not much room for them to shift further to the right. On other questions, by contrast, there is more variation within the GOP.

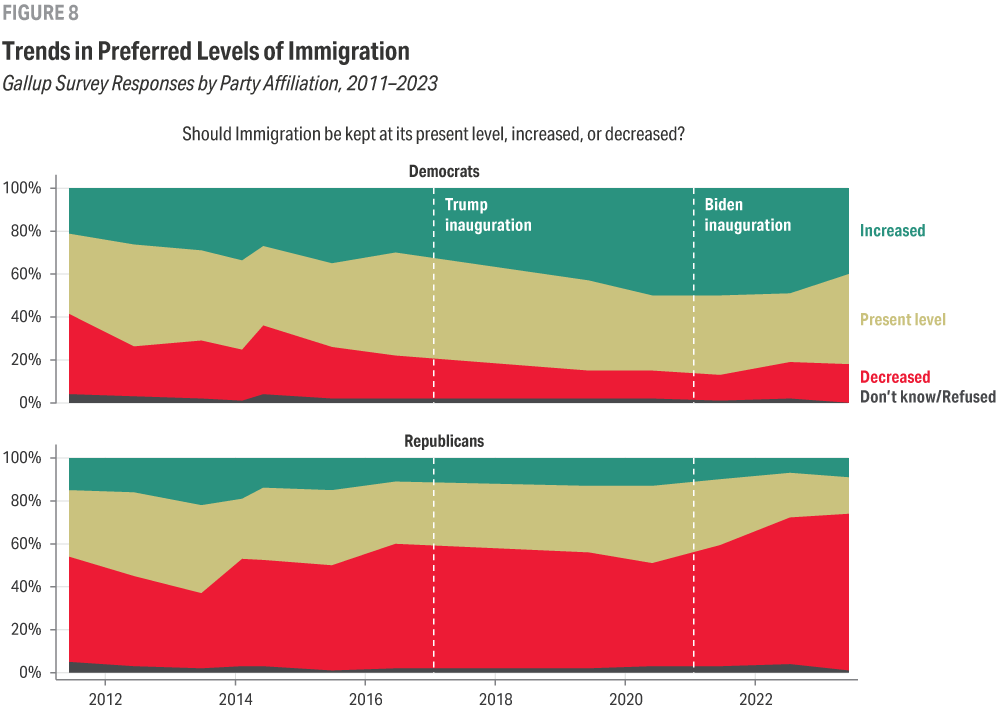

One example has to do with preferred levels of immigration to the U.S. Since 1965, the Gallup polling organization has asked whether people want to increase or decrease immigration to the country or keep it at its present level. Partisan differences on this question emerged gradually beginning in the early 2000s and then accelerated during the Trump administration. Again, this was largely due to a liberal shift among Democrats (Figure 8).17

However, since Biden was inaugurated, there has been a dramatic change in Republican attitudes. The percentage of Republicans who want to decrease immigration rose by 25 percentage points in two years — from 48 percent to 73 percent, as of June 2023 (Figure 8). In the most recent survey, more Republicans wanted to decrease immigration than at any point in Gallup’s polling for the past 60 years. Democrats have shifted in the same direction, but by less.18

A different way of asking about a path to citizenship for undocumented immigrants also shows a partisan asymmetry. In surveys by the firm Civiqs since Biden’s election, there has been a 17-point increase in the percentage of Republicans who prefer to “deport immigrants living here illegally” instead of giving them a “path to citizenship.” As of December 2023, 81 percent prefer deportation. Meanwhile, 82 percent of Democrats prefer a path to citizenship when the question is framed that way, which represents a 7-point drop since Election Day 2020.19

Consistent with this increasingly restrictive sentiment toward undocumented immigrants, public support for the U.S.-Mexico border wall has also increased.20

The Evolution of Immigration Politics

We have shown some de-polarization on attitudes about racial inequality and discrimination since 2020 — with Democrats moving a little to the right and Republicans a little to the left — but more polarization on immigration attitudes, with both parties shifting to the right but Republicans shifting further. The differences in these two sets of trends means that underlying factors behind the immigration trends are not exactly the same as those behind trends in attitudes about race.

One common factor is the reaction to Trump’s rhetoric and policymaking. Trump staked out quite conservative positions on these issues during his 2016 campaign and then sought to implement them. His immigration policymaking included efforts to restrict immigration and punish undocumented immigrants, including the infamous program of family separation at the U.S.-Mexico border. Thus, Democratic voters who were initially less liberal on immigration policy shifted to the left for the same reason they did on racial issues: Their aversion to Trump led them to move their attitudes in the opposite direction.

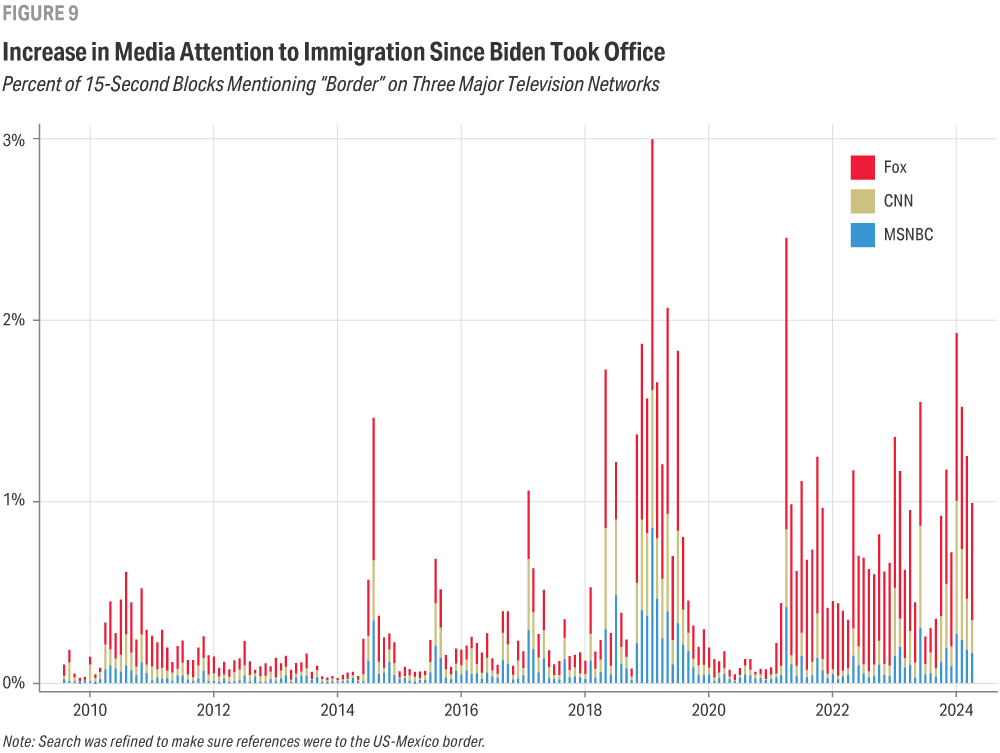

Two things have changed under Biden. First, there has been an increase in media attention to immigration since Biden took office. For example, the number of mentions of the word “border” on major cable news networks has been consistently higher under Biden’s presidency than during Obama’s and Trump’s (Figure 9). This reflects both the increase in border crossings during Biden’s presidency and the agenda of more conservative outlets. Most of the monthly mentions of the border on these cable networks are on Fox News.

These factors have combined to increase the salience of immigration to American voters — particularly Republicans.21 In the 2020 VOTER Survey, 47 percent of Americans said that immigration was “very important.” This increased to 54 percent in 2024 (see Figure 6). Thus, over these four years, fewer Americans saw racial equality as an important issue but more saw immigration as important.

The second change under Biden concerned his policymaking and rhetoric. In some ways, Biden broke with Trump. For example, he canceled Trump’s executive actions that restricted immigration from certain Muslim-majority countries and reversed a Trump policy that cracked down on cities who would not cooperate with federal immigration agents.

At the same time, Democratic and Republican leaders have offered broadly similar messages about the need for more border enforcement. Of course, Republicans have harshly criticized Biden’s handling of immigration and called for a raft of new security measures. Republican politicians, especially Texas Governor Greg Abbott, have pursued their own enforcement policies.

But many Democratic leaders have also expressed concerns about the border. One example is local Democratic leaders in New York City and elsewhere who have faced influxes of immigrants and the need to provide services for them. Biden himself endorsed a bipartisan bill that would have provided for stricter enforcement, although it was ultimately killed by Republicans who seemed unwilling to give the Biden administration a legislative victory in an election year. Biden then pursued action on his own in June 2024, announcing restrictions on immigrants seeking asylum at the U.S.-Mexico border.

This combination of events, news coverage, and relative partisan consensus on border security helps explain why Democrats and Republicans have moved toward more conservative positions. With some degree of agreement between prominent Democrats and Republicans, Democratic and Republican voters should trend in the same direction, as they generally have.

However, Republican leaders and the conservative news media have focused more on immigration than Democratic leaders, which may have led to a stronger reaction among Republican voters. In addition to the disproportionate amount of coverage coming from conservative outlets, data on how members of Congress communicate with constituents also show that Republican members mention immigration at a far higher rate than Democratic members do.22

Thus, as Figure 6 shows, the change in the percent of Americans who think that immigration is a “very important” issue is much larger among Republicans — from 58 percent in 2020 to 74 percent in 2024 — than among Democrats (41 percent in 2020 vs. 39 percent in 2024). It is no surprise, then, that Republicans shifted more than Democrats in favor of reducing immigration.

Conclusion

The trends in public opinion about racial inequality, discrimination, and immigration under Trump and Biden are a noteworthy departure. White Americans’ views about racial inequality and discrimination were virtually unchanged under Democratic and Republican presidents alike from 1988 to 2012 — what Christopher DeSante and Candis Watts Smith have described as a time of “racial stasis.”23 Under Trump, however, there were large shifts in attitudes about both race and immigration, mostly among Democrats who moved toward a more liberal stance. Under Biden, Democrats are a bit less liberal and Republicans a bit more liberal on racial issues in particular, creating a very modest decrease in partisan differences. On immigration, both parties have shifted to the right — but such shifts are at times larger among Republicans than Democrats.

We trace these trends to changes in the information environment — including the rhetoric and positions of Trump and Biden as well as the work of activists, social movements, and the news media. Trump eschewed a dog-whistle politics of code words that had long characterized Republicans’ messaging on race and instead made explicit racial appeals to white Americans.24 Democratic politicians, meanwhile, have become increasingly vocal in their support for racial equality. Especially after the murder of George Floyd, the Black Lives Matter movement focused attention on racial injustice and the conduct of police. All of this helped push Democratic voters toward more liberal views on race.

However, Trump’s and others’ attacks on this movement helped create a backlash, ensuring that there would be no broader shift among Republicans toward acknowledging or seeking to overcome racial injustice.25 And after the racial justice protests in the summer of 2020, the news media devoted less attention to topics related to racism. As a result, fewer Americans cited racial equality or police reform as major issues. And as president, Biden has pursued more moderate rhetoric and policies. Fewer Americans perceive Biden as favoring some racial groups over others, relative to Trump. All of these factors have helped produce modestly smaller partisan differences on racial issues.

On immigration issues, however, the story is different. There was the same liberal shift among Democrats during Trump’s presidency. But since then, the combination of record crossings at the U.S.-Mexico border, Biden’s own embrace of border enforcement, and criticism of his policies by Republican politicians has produced more restrictive public attitudes overall and sharp conservative shifts among Republican voters on issues like deportation.

The upshot of these trends is that attitudes about racial inequality, discrimination, and immigration appear to fit a popular model of public opinion: the thermostatic model of policy attitudes. In the thermostatic model, the public’s policy attitudes shift against the current president’s policies in response to real or perceived changes in the status quo — just like a thermostat will cool down a house when it gets too hot, or heat it up when it gets too cold.26

Thermostatic patterns have been frequently documented in attitudes toward government spending and programs. For example, Americans’ support for universal government health insurance dropped during Obama’s presidency and then increased as the Trump administration tried to repeal the Affordable Care Act in 2017.27 But for a long time, issues related to race and immigration did not display these thermostatic patterns.28

That no longer appears to be the case. The key reason is how the parties themselves have changed. With the two parties pushing in opposite directions on race and immigration even more than in the past, the public appears to be pushing back, with their opinions on these issues shifting to the left under Trump and back to the right under Biden. The emergence of these thermostatic patterns reflects the centrality of race and immigration to current partisan politics.

Moreover, this thermostatic pattern suggests a different story about what has happened, and may yet happen in U.S. politics. One theme in commentary about American opinion and policymaking on racial issues and immigration is that the country experienced a temporary “Great Awokening” that ultimately did not last. “Wokeness has peaked,” is now commonly invoked to describe American attitudes since 2020.29

But this interpretation does not fit some empirical patterns. For one, a number of survey questions show that much of the change experienced during this period has persisted. For another, on some questions about racial inequality Democrats and Republicans have moved in opposite directions. “Wokeness has peaked” does not help us understand why Democrats seem a bit less likely to express liberal attitudes about racial inequality but Republicans a bit more. Changes in elite opinion leadership — and particularly the contrast between Trump and Biden — provides a better explanation. Moreover, the trends in opinion differ, both overall and within parties, when the issue at hand is immigration rather than racial inequality. This too appears to derive from a combination of events, like the increase in border crossings, and how political leaders have responded to and communicated about those events.

Finally, if thermostatic patterns continue to characterize public opinion on these issues, then we should not anticipate a single peak in these attitudes followed by an inexorable decline. We should instead anticipate an ebb and flow in public opinion that depends on the party of the president, the direction of policymaking, and the messages citizens receive from political leaders. These predictable patterns may become the new “racial stasis” in American politics.

- Tankersley, Jim, and Michael D. Shear. 2021. “Biden Seeks to Define His Presidency by an Early Emphasis on Equity.” New York Times, January 23. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/01/23/business/biden-equity-racial-gender.html [↩]

- Statement from President Joe Biden On the Bipartisan Senate Border Security Negotiations, January 26, 2024. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2024/01/26/statement-from-president-joe-biden-on-the-bipartisan-senate-border-security-negotiations/ [↩]

- On the development of this measure, see Donald R. Kinder and Lynn M. Sanders, “Divided by Color,” Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996. On its meaning, see Cindy D. Kam and Camille D. Burge, “Uncovering Reactions to the Racial Resentment Scale across the Racial Divide,” The Journal of Politics, 2019, 80(1): pp. 314–320. [↩]

- Griffin, Robert, Mayesha Quasem, John Sides, and Michael Tesler. 2021. Racing Apart. Democracy Fund Voter Study Group. See: https://www.voterstudygroup.org/publication/racing-apart [↩]

- Engelhardt, Andrew M. 2023. “Observational Equivalence in Explaining Attitude Change: Have White Racial Attitudes Genuinely Changed?” American Journal of Political Science, 67: 411–425. [↩]

- Although the sample sizes for Asian-American Democrats in these VOTER Survey waves are not large, the same patterns emerge in the Cooperative Election Study, a different survey project, which has much larger samples. Further analysis shows similar trends across education groups among white Americans. [↩]

- The decline in the number of Democrats who said that Black people face a lot or a great deal of discrimination was evident in Democrats of all major racial and ethnic groups. Even among Black Democrats, there was a modest decline (from 89 percent to 82 percent). The declining number of Democrats saying that Latino people face high levels of discrimination was also evident across racial and ethnic groups, including Latino Democrats. [↩]

- John Sides, Chris Tausanovitch, and Lynn Vavreck. 2022. The Bitter End: The 2020 Presidential Campaign and the Challenge to American Democracy. Princeton: Princeton University Press. Chapter 9. [↩]

- Robert Griffin, Mayesha Quasem, John Sides, and Michael Tesler. 2021. Racing Apart. Democracy Fund Voter Study Group. https://www.voterstudygroup.org/publication/racing-apart [↩]

- Two large-scale studies of elite leadership are: John Zaller. 1992. The Nature and Origins of Mass Opinion. New York: Cambridge University Press; and Gabriel S. Lenz. 2012. Follow the Leader?: How Voters’ Respond to Politicians’ Policies and Performance. Chicago University Press. On how partisans may react against the opposite party’s cues, see Stephen P. Nicholson. 2011.“Polarizing Cues.” American Journal of Political Science 56 (1): 52–66. [↩]

- John Sides, Chris Tausanovitch, and Lynn Vavreck. 2022. The Bitter End: The 2020 Presidential Campaign and the Challenge to American Democracy. Princeton: Princeton University Press; Robert Griffin, Mayesha Quasem, John Sides, and Michael Tesler. 2021. Racing Apart. Democracy Fund Voter Study Group. https://www.voterstudygroup.org/publication/racing-apart [↩]

- For the underlying data, see: https://api.gdeltproject.org/api/v2/summary/summary?d=iatv&t=summary&k=%28racism+OR+%22black+lives+matter%22+OR+%22george+floyd%22%29&ts=full&fs=station%3ACNN&fs=station%3AFOXNEWS&fs=station%3AMSNBC&svt=zoom&svts=zoom&swvt=zoom&ssc=yes&sshc=yes&swc=yes&stcl=yes&c=1 [↩]

- This relationship between media attention to an issue and its perceived importance within the public is a conventional finding in political science research. See Iyengar, Shanto, and Donald R. Kinder. 1987. News That Matters: Television and American Opinion. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [↩]

- Perhaps relatedly, public support for Black Lives Matter has also fallen from its high point after George Floyd’s murder. See: https://civiqs.com/results/black_lives_matter?uncertainty=true&annotations=true&zoomIn=true. [↩]

- In fact, we found that the less favorably white Americans felt toward Trump in 2020, the more their views of racial inequality shifted in a conservative direction between 2020 and 2024. [↩]

- Anthony Salvanto, Jennifer De Pinto, and Fred Backus. 2023. “If Trump wins, more voters foresee better finances, staying out of war.” CBS News, November 5. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/trump-vs-biden-poll-2024-presidential-election-year-out/ [↩]

- See also Trent Ollerenshaw and Ashley Jardina. 2023. “The Asymmetric Polarization of Immigration Opinion in the United States.” Public Opinion Quarterly 87 (4): 1038–1053. [↩]

- There is a similar pattern in the General Social Survey’s question about levels of immigration. For example, from 2016 to 2020, the percent of Democrats who supported increasing immigration grew from 25 percent to 39 percent. Republican support for decreasing immigration grew from 53 percent to 60 percent between 2018 and 2022. Changes in survey mode in the General Social Survey during 2021–22 complicate the ability to make comparisons over time, but these changes resemble what Gallup polls found. [↩]

- See: https://civiqs.com/results/immigrants_citizenship?uncertainty=true&annotations=true&zoomIn=true. [↩]

- Michael Tesler. 2023. “Why the border wall is getting more and more popular.” Good Authority, November 3. https://goodauthority.org/news/why-the-us-border-wall-is-getting-more-popular/ [↩]

- A long line of research has shown that the volume of news coverage about an issue affects how important people think that issue is. See, for example, Shanto Iyengar and Donald Kinder. 1989. News that Matters. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [↩]

- This is based on a search for the word “immigration” in the database of Congressional email newsletters maintained by political scientist Lindsey Cormack at dcinbox.com. Republican mentions of immigration have outpaced Democratic mentions since Biden’s election. For example, in the period between September 14, 2023, and April 9, 2024, 1,425 GOP emails mentioned immigration, compared to 497 Democratic emails. [↩]

- Christopher D. DeSante and Candis Watts Smith. 2020. Racial Stasis: The Millennial Generation and the Stagnation of Racial Attitudes in American Politics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [↩]

- Rogers M. Smith and Desmond King. 2021. “White Protectionism in America.” Perspectives on Politics 19 (2): 460–478. [↩]

- Jefferson, Hakeem, and Victor Ray. 2022. “White Backlash is a Type of Racial Reckoning, Too.” FiveThirtyEight, January https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/white-backlash-is-a-type-of-racial-reckoning-too/ [↩]

- The canonical study is Christopher Wlezien. 1995. “The Public as Thermostat: Dynamics of Preferences for Spending.” American Journal of Political Science 39 (4): 981–1000. [↩]

- See polling by the Pew Research Center and Gallup: https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2018/10/03/most-continue-to-say-ensuring-health-care-coverage-is-governments-responsibility/. [↩]

- Mary Layton Atkinson, K. Elizabeth Coggins, James A. Stimson, and Frank R. Baumgartner. 2021. The Dynamics of Public Opinion. New York: Cambridge University Press. However, some prior work has identified the possibility of thermostatic dynamics in attitudes toward government policies that affect Black Americans. See: Paul M. Kellstedt. 2000. “Media Framing and the Dynamics of Racial Policy Preference.” American Journal of Political Science 44 (2): 245–260. There is also evidence of thermostatic dynamics in Western European attitudes about immigration. See: Van Hauwaert, Steven M. 2023. “Immigration as a thermostat? Public opinion and immigration policy across Western Europe (1980–2017).” Journal of European Public Policy 30 (12): 2665–2691. [↩]

- Yglesias, Matthew. 2019. “The Great Awokening.” Vox, April 1, https://www.vox.com/2019/3/22/18259865/great-awokening-white-liberals-race-polling-trump-2020. There are many pieces about “peak wokeness.” See, for example: Cowen, Tyler. 2022. “Wokeism has peaked.” Bloomberg, February 18, https://www.bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2022-02-18/wokeism-has-peaked-in-america-but-is-still-globally-influential; or Traldi, Oliver. 2022. “Peak Woke?” City Journal, July 6, https://www.city-journal.org/article/peak-woke. [↩]