This blog was co-authored by Francesca Mazzola, Associate Director at FSG.

Three Important Lessons About Trust

At Democracy Fund, we have been exploring questions of trust. Trust in institutions is at an all-time low. In 2016, for example, only 32% of Americans said they had a “Great Deal” or “Fair Amount of Trust” in mass media, the lowest level of trust in Gallup polling history.

Meanwhile, research suggests (1) that higher levels of trust lead to: a) greater confidence in trusted individuals or institutions and b) a willingness to act based on that confidence. In the context of our national relationship to the news media, for instance, this implies that a significant majority of Americans may not be willing to act civically or otherwise based on the information provided by mass media outlets.

Given that democracies function best when individuals participate in the civic process (e.g. voting, running for office, volunteering), it is clear that the current low level of trust in public institutions (including, but not only, the media) is a problem in need of attention. A healthy democracy requires institutions that are both trustworthy and trusted.

As we’ve been investigating the notion of trust, three important lessons have become apparent to us:

1. Trust has both cognitive and affective dimensions

Think about someone you trust. Now think about the reasons why you trust that person. More than likely, they have a good “track record” of having been there for you when you needed them. In addition, you probably have an emotional bond with them that allows you to be vulnerable. This exemplifies the two dimensions of trust – cognitive and affective. (2)

Cognitive trust has been described as “trusting from the head.” It includes factors such as dependability, predictability, and reputation. Affective trust, on the other hand, involves having mutual care and concern or emotional bonds. This has been described as “trusting from the heart.” Most trusting relationships have both cognitive and affective aspects that often reinforce one another.

2. Trust and trustworthiness are not the same

One way to understand trust is that it is a firm belief (cognitive and affective) in the goodness of something (we use the word “goodness” deliberately here, as dictionary definitions of trust tend to use descriptors of trustworthiness instead). We are often willing to trust people, companies, and institutions because we believe they are good, at least in the context in which we trust them.

Trustworthiness is a related, but different notion. Trustworthiness is defined as the perceived likelihood that a particular trustee will uphold one’s trust. (3) Like trust, it also has cognitive dimensions (such as competence, credibility, and reliability) and affective dimensions (such as ethics and positive intentions) that signal that the trustee “has what it takes” to meet the trustor’s needs and uphold their trust.

Imagine your interaction with your bank. Though you don’t necessarily need to trust the bank (i.e. believe in its “goodness”) as you would trust a spouse or a close friend, you must believe that the bank is trustworthy – i.e., it completes your transaction as intended, obeys laws, and follows a code of ethics. But you have to have trust in the overall monetary and financial system to even feel safe opening a bank account – something that was adversely affected after the financial crisis.

3. Trustworthiness and trust have a counter-intuitive relationship

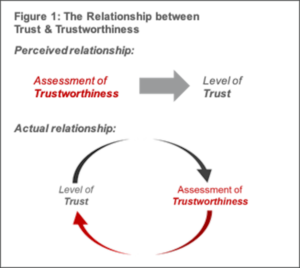

A rational point of view of the relationship between trustworthiness and trust would suggest that when you first encounter a system, you make an assessment of its trustworthiness (e.g., competence, predictability), and then you calibrate your level of trust accordingly.

But, alas, human beings are anything but rational. The evidence around human cognition and reasoning increasingly points to a counter-intuitive relationship: often, we enter into a new relationship (with a person or a system) with a level of trust that is influenced by the “bubbles” (i.e. communities and networks populated by like-minded folks) that we inhabit.

From there, we look for information to confirm our initial instincts (often referred to as “confirmation bias”). The type of information we look for or prioritize (e.g., cognitive vs. affective factors) varies by individual and by situation. This phenomenon help us understand, for instance, why individuals trust a news source that is perceived to be more aligned with their political views.

What this means

In the light of these dynamics, improving the trustworthiness of a system is often necessary and vital, but perhaps insufficient as a way to build public trust. Of course, we want to prevent a crisis of trustworthiness from eroding trust. For instance, public trust in Japan’s institutions suffered a severe blow as a result of the government’s bungled response to the Fukushima disaster in 2011. But, ensuring trustworthiness on its own may not be enough to overcome the contextual forces that undermine trust in the first place.

Furthermore, some efforts to improve trustworthiness, such as technical improvements to a system, are shown to decrease trust in the short-term, by introducing unpredictability as people have to navigate an unfamiliar tool or process. As we will discuss in the next part of this post, these complicated dynamics will have to be kept in mind as one tries to navigate the work of re-building trust in democratic institutions.

How We Are Strengthening Trust and Trustworthiness

For the Democracy Fund, and anyone else working on improving American democracy, it is hard to ignore the fact that trust in institutions is remarkably low by historical standards. This is especially true for Democracy Fund’s three main areas of focus – media and journalism, Congress, and elections. There are several factors that have led to this. For instance, our Congress and Public Trust systems map explores how the actions of members of Congress and their staff, the media, and the public interact to create the current state of Congress.

Previously, we talked a bit about why this decline in trust matters. The question now becomes, “can anything be done about it?” And in our efforts to do something about it, do we focus on trust, trustworthiness, or both?

The “trust matrix”

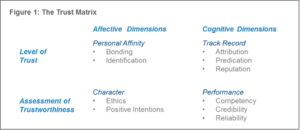

As we discussed previously, level of trust and assessment of trustworthiness are related, but different notions, and each has cognitive and affective dimensions. These concepts are organized below into what we’ve come to call the trust matrix. The matrix also provides labels (e.g., “personal affinity”) to help readers easily navigate the differences among categories of concepts.

Implications for Democracy Fund

We recognize that in order to restore trust in democratic institutions, we need to work on multiple fronts. This by no means an easy task. Philanthropy, in general, tends to focus on solutions that address trustworthiness. For instance, an effort to improve education may focus primarily on educator competencies, or work to create a set of proficiency standards.

This may be because it can be a lot harder to affect people’s personal affinity for individuals or institutions, or public perceptions of individuals’ or institutions’ characters. While there may be few “tried and true” methods to address these factors, they are nonetheless important pieces in affecting individuals’ trust in systems and institutions. At the same time, it’s important to acknowledge that there are potential ethical implications with influencing people’s belief systems, and hence a responsible framework needs to be considered.

As we grapple with the myriad of intricacies here, we are beginning to come to terms with what types of approaches may fit under each quadrant of trust matrix. Below are some early hypotheses:

- Trustworthiness: We must increase the trustworthiness of institutions by equipping key stakeholders with better tools and practices (cognitive), and the promulgation and adoption of better standards and ethics (affective). For our elections work, this might mean identifying standards and promoting security in election systems, and providing election officials with the resources they need to maintain system integrity. Any failure within our election system could seriously undermine public trust. For our media and journalism work, this may mean re-thinking how we make the case for fundamental facts and combat misinformation, as well as working on practices around transparency and corrections.

- Level of Trust: We also need to tackle the trust deficit through strategies that speak directly to the public through engagement tools (cognitive) and the use of bonding and identification (affective). For our elections work, this may mean empowering the right messengers with tools and tactics to improve voter confidence. For our media and journalism work, this may mean having specific strategies that emphasize improving trust among historically marginalized communities, and other groups with special attention to increasing the diversity and inclusion of sources, stories and staffing.

At a time when our democratic norms are often undermined, we hope that our work to strengthen trust in trustworthy institutions will help build public confidence and participation in our democracy. As we continue to develop and hone our approach, we look forward to learning and sharing more with the field.

Thanks to Marcie Parkhurst, Nikhil Bumb, and Jaclyn Marcatili from FSG for supporting the research that informed this piece.

Works Cited:

1. Kelton, Kari. “Trust in Digital Information.” Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology (2008): 363-74.

2. McAllister, D. J. “Affect- And Cognition-Based Trust As Foundations For Interpersonal Cooperation In Organizations.” Academy of Management Journal 38.1 (1995): 24-59

3. Colquitt, Jason A. “Justice, Trust, and Trustworthiness: A Longitudinal Analysis Integrating Three Theoretical Perspectives.” The Academy of Management Journal, vol. 54, no. 6, 1 Dec. 2011, pp. 1183–1206. JSTOR.