Introduction to “Stewards of Democracy,” a series on findings from the 2020 Democracy Fund/Reed College Survey of Local Election Officials

Political observers expected the 2020 presidential election to be competitive and politically contentious long before it happened, but when the first caucuses and primaries kicked off early last year, few anticipated the enormous impact and unpredictable trajectory that the COVID-19 pandemic would have on state and local election administrators, their staff, and on the voting public. Yet as we know today, the system proved resilient in the face of this crisis. Voter turnout rates in November 2020 were the highest in over a century. Local election officials across the United States truly delivered democracy.

Today we begin a series of blog posts presenting perspectives and lessons learned from those who served in 2020 and lived the election every day as they administered one of our democracy’s most critical functions.

Local election officials are key authorities on how elections actually work. Their experiences shed light on how well our election system performs and what changes should be put into place to maintain efficient, accessible, equitable, and resilient elections in the future. Especially in this fraught historical moment, when the system has come under attack by both domestic and foreign actors, the insights, beliefs, and opinions of this group should be amplified.

Listening to the Stewards of Democracy

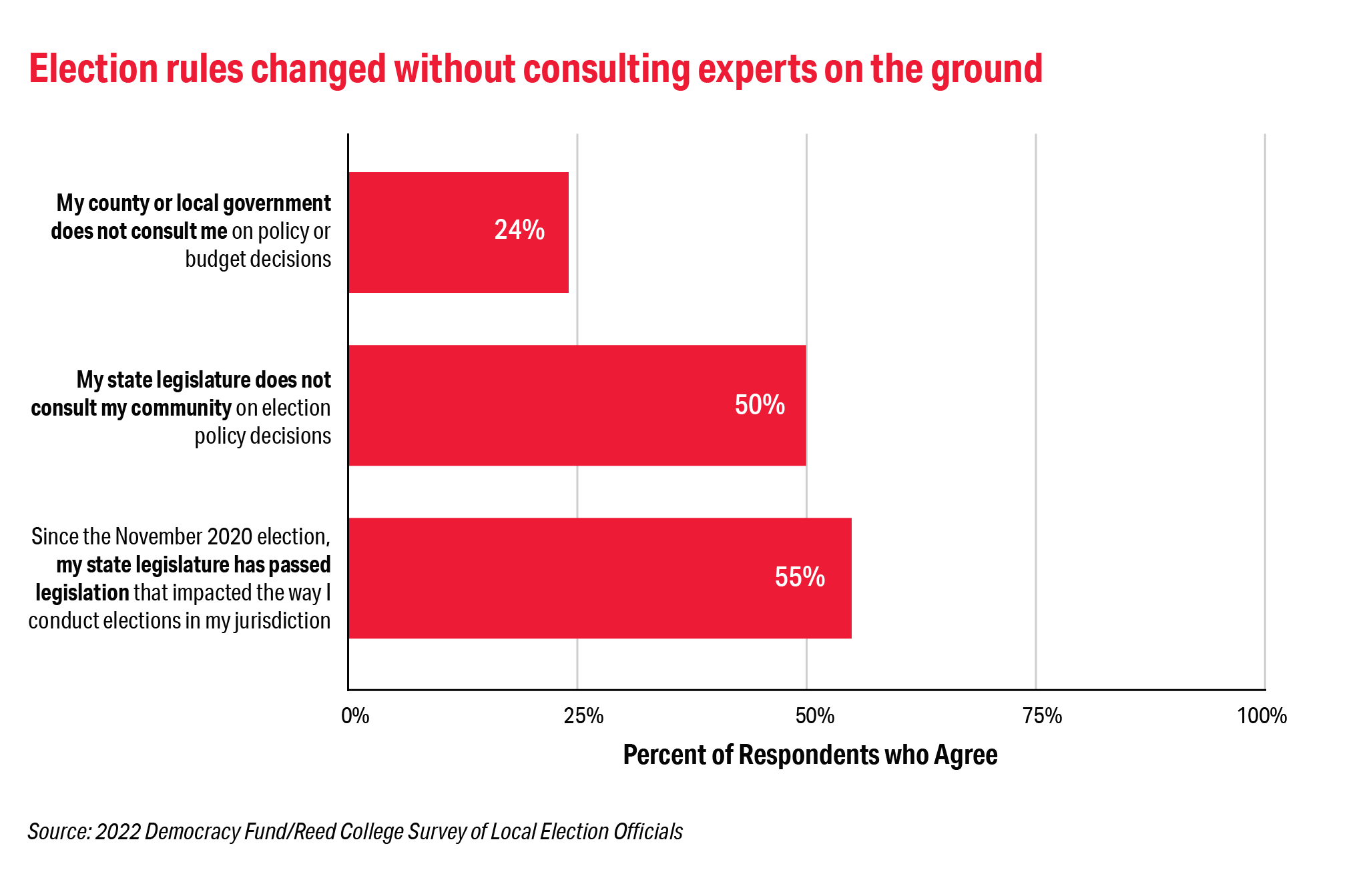

Election administration in the United States is highly decentralized. States and localities share the primary responsibilities for election administration with limited federal influence. State legislatures are the primary body invested with the responsibility for passing laws pertaining to election administration, and elections officials and some state regulatory boards provide oversight and advice to legislatures. While a few provisions in the U.S. Constitution provide a role for federal authority, the ultimate balance of federal, state, and local influence and control is constantly in tension — moving and changing, and subject to political, legal, technological, and economic forces.

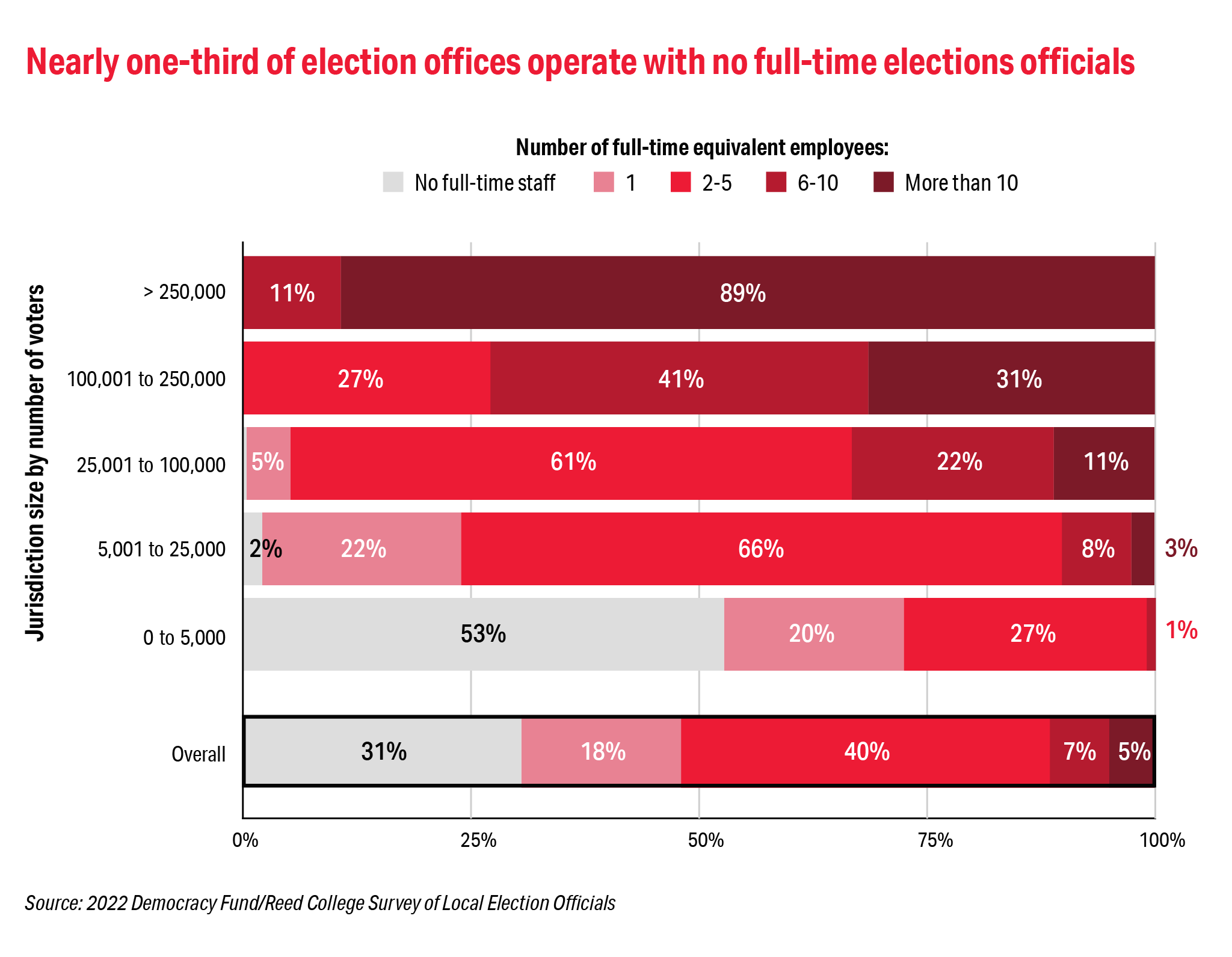

America’s local election officials, as well as the offices they organize and staff they oversee, work at the intersection of these forces. Over 8,000 individuals serve as local clerks, chief clerk-recorders, supervisors, auditors, registrars, and other positions in counties, municipalities, and townships across the country. Together, these officials administer elections and deliver democracy to hundreds of millions of American citizens.

The Democracy Fund/Reed College Survey of Local Election Officials is intended to amplify and elevate the voices of these experts, understand their experiences and perspectives, and contribute to conversations about election administration and reform. In this series as in past reports, we refer to these street-level bureaucrats as the Stewards of Democracy because they are invested with the responsibility of managing and caring for voting and elections.

In upcoming posts, we will cover a variety of timely topics and offer the latest findings from our survey, including:

- Less than half of local election officials thought that voters were sufficiently informed of USPS delivery times to return their mail ballots in time in the November 2020 election.

- Almost three-quarters of local election officials consider voter education and satisfaction to be part of their responsibilities.

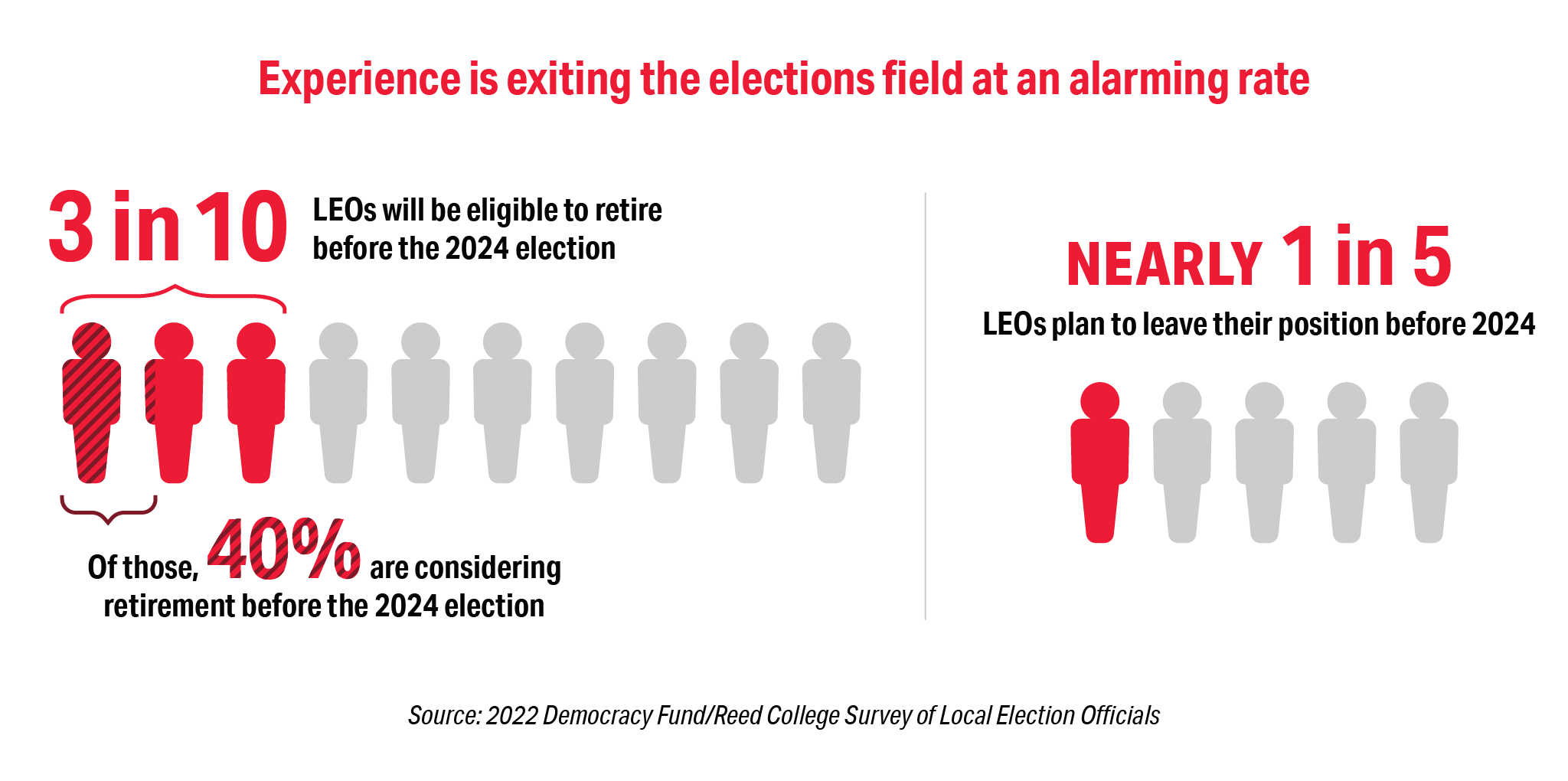

Almost 35 percent of local election officials will be eligible to retire before the 2024 election, including more than half of those in the largest jurisdictions (defined as serving more than 250,000 registered voters).

About the Survey and Interviews

The Democracy Fund/Reed College Survey of Local Election Officials and reports of its findings provide insights from local election officials across the country into the state of our elections system, election policies, and voter-centric practices.

In 2020, this survey was conducted online and sent to 3,000 randomly selected chief local election officials — those in charge of elections in their jurisdiction. We used a sampling methodology that increases the probability of selection based on the number of registered voters in the jurisdiction. Total responses were 857, for a response rate of 29 percent, which is slightly lower than the response rates to the 2018 and 2019 surveys, but still comparable to past surveys of this population.

Survey findings are often presented by jurisdiction size to understand differences in experiences.

- Fifty-eight percent of local election officials serve in jurisdictions of 5,000 or fewer voters.

- Twenty-seven percent serve in jurisdictions of 5,001 to 25,000 voters.

- Ten percent serve in jurisdictions of 25,001 to 75,000 voters.

- Six percent serve in jurisdictions of more than 75,000 voters.

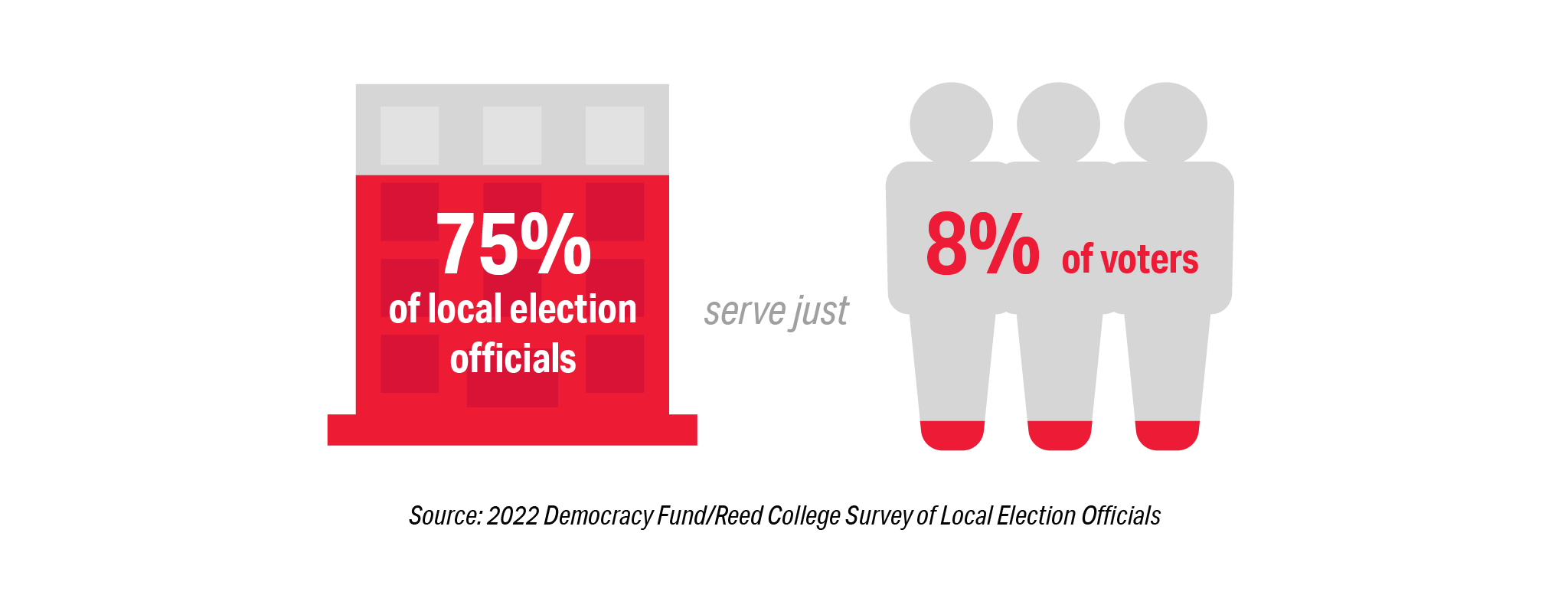

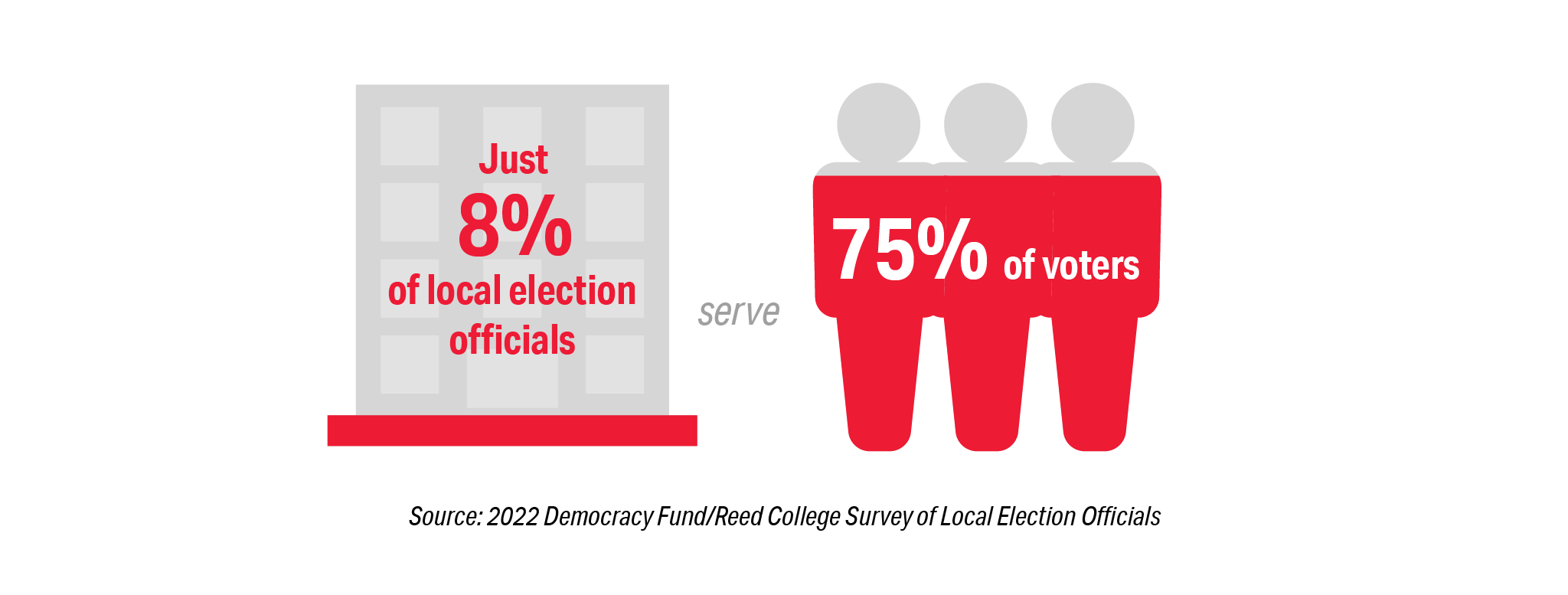

While most officials serve in small jurisdictions, the vast majority of voters live in large jurisdictions — over 70 percent of voters live in jurisdictions with more than 75,000 voters and are served by only 500 officials. It’s important to consider the possible differences in scale, responsibility, and resources between different jurisdiction sizes when interpreting results from any survey of this population. Where overall results are presented, they are weighted to ensure that means can be generalized to local election officials nationwide. Further information about the sampling and weighting process is available at the Reed College Early Voting Information Center’s project website.

In addition to quantitative findings and open-ended responses from the survey, this blog series will also feature the words of officials from a set of in-depth interviews conducted by the Fors Marsh Group. Officials interviewed were chosen from varying states, jurisdiction sizes, elective/appointive histories, and tenures in office. For more information, see the report on this study.