In late September, the LA Times editorial board wrote, “For at least its first 80 years, the Los Angeles Times was an institution deeply rooted in white supremacy.” This editorial was the start of an eight-part series interrogating the Times’ history of racist coverage and its failure to represent the communities it purported to serve in staffing, stories and sources. This deep reflection is a good first step for the paper, and a necessary one for the entire industry. But the next step must be action — from the LA Times, from other newsrooms, and from the journalism funders who support them.

The next step must be action — from the LA Times, from other newsrooms, and from the journalism funders who support them.

One year ago, a group of concerned program officers from foundations across the country (many of whom are former journalists) sat down together in a classroom at the Craig Newmark Graduate School of Journalism at CUNY to talk through not only the racist structures that undergird traditional outlets like the LA Times — but also those that shape philanthropic efforts aiming to transform journalism. We wanted to connect the dots and find opportunities for action. And we did — in a newly released report called, “Equity First: Transforming Journalism and Journalism Philanthropy in a New Civic Age,” created by Frontline Solutions.

The report comes as our nation marks eight months and more than 210,000 deaths from the coronavirus pandemic, which has disproportionately affected Black, Latino and Native American communities, and as the country continues to reckon with the deaths of Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, and George Floyd. Together, these events have sparked a massive racial justice movement in the United States and across the world, and as advocates continue to march, journalists of color are demanding accountability in their newsrooms.

Journalists of color are demanding accountability in their newsrooms.

For years, many of these journalists have felt a dissonance between the kinds of reporting they know communities need, and the false “balance” and harmful narratives white newsroom culture have perpetuated. And now they’re taking action. In June, journalists of color at the Philadelphia Inquirer called in sick and tired in response to a tactless headline that belittled the nature of protests around Black Lives Matter. Staff members called for the resignation of a New York Times opinion editor for publishing an op-ed that suggested invoking the Insurrection Act to snuff out protests following the death of George Floyd. And then union members at the LA Times put together a list of demands for its new owner to transform coverage and staffing.

Many of us are not surprised by what is happening in newsrooms right now. “Equity First: Transforming Journalism and Journalism Philanthropy in a New Civic Age” is rooted in what The Kerner Commission of 1968 found: that the extreme lack of media diversity and equity is a driving force of inequality. As we marked Kerner’s 50 year anniversary in 2018, journalists noted how little progress the field overall has made in centering stories from historically marginalized communities. And philanthropy has persistently underinvested in organizations that are led by and serving these communities.

It’s time to do more. Our new report outlines three longstanding barriers to equity-centered journalism and grantmaking within journalism philanthropy:

1) Journalism’s prized ethics and values aren’t translating to DEI best practices.

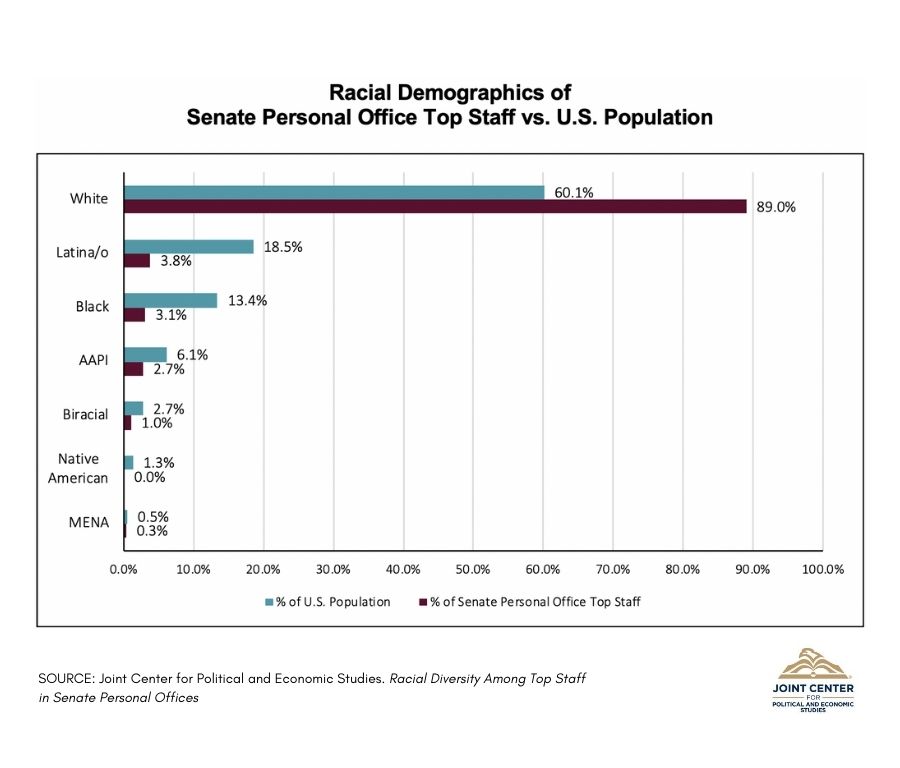

Despite journalism’s stated values of accuracy, upholding the truth and elevating unheard stories, there is not enough acknowledgment that it is impossible to live these values in a newsroom whose leadership does not reflect the diversity of the country. The result is newsrooms that are ill-equipped to create resonant and relevant content for their constituents — much less protect them from disinformation actors (such as Russian interference campaigns) that have disproportionately targeted Black audiences. These failures widen the trust gap between communities of color and newsrooms.

2) The inherent cultures of journalism and philanthropy commonly reinforce white masculine norms.

Journalism tends to reinforce the myth of objectivity without considering who gets to decide whose narrative is grounded in reality…meaning that the white, male perspective is the default. Adding to the problem, journalism prioritizes urgency over taking the time to be inclusive, thoughtful or nuanced. And it upholds the paternalistic idea that newsrooms should decide what communities should know rather than practicing deeper engagement and relationship building.

Decision-making within philanthropy has similar flaws. It can occur in a vacuum and in ways that can be paternalistic and lack nuance. This is especially true when funders deploy rapid response funds — as many did during the early part of the pandemic — without taking time to diversify potential recipients and challenge our existing networks. Funders also tend to assume that resources are fairly allocated without critically examining structural inequities around accessing capital.

3) Foundations focus on addressing diversity because it feels most tangible. But what about inclusion and equity?

A diverse staff does not automatically make for an equitable workplace. To get there, power and decision-making authority have to shift. This work requires inclusion, and prioritization, of communities who have not had a seat at the table. Because both journalism and philanthropy have hierarchical structures that makes this kind of shift difficult, they tend to preserve power where it already is.

These challenges are complex, longstanding, and at the core of both philanthropy and journalism. But they are not insurmountable. The report highlights several steps that funders can take to change their internal structures and practices in order to address inequity, which will help make the news that we support more equitable as well. Our recommendations include:

- Center equity in our definitions and funding of innovation;

- Invest in leadership and emerging talent within communities of color;

- Map and then move decision-making power to affected communities.

This past year has tested the spirit, health, and lives of communities of color, especially Black communities. But we know this fight for justice has endured for centuries. Early data suggests a long-needed shift in dollars is underway: Over $4.2 billion philanthropic dollars have gone to racial equity in 2020, compared to $3.3 billion dollars between 2011–2019. That’s 22 percent more funding this year than in the past nine years combined.

The question now is, “can philanthropy and journalism sustain this change?”. These investments must be matched by new systems, practices, and thinking. They must be sustained, not sporadic. They must put communities directly affected at the center of decision-making rather than an afterthought. And they must trust that these communities have solutions to the problems they face, because they have been working to solve them for as long as they have existed.

This is the only way philanthropy and journalism can invest in communities of color if we hope to be a part of the solution.

Liz Baker

Senior Manager, Independent Journalism and Media, Humanity United

Lolly Bowean

Media and Storytelling Program Officer, Field Foundation

LaSharah S. Bunting

Director of Journalism, Knight Foundation

Paul Cheung

Director of Journalism and Technology Innovation, Knight Foundation

Farai Chideya

Program Officer, Creativity and Free Expression, Ford Foundation

Jenny Choi

Director of Equity Initiatives, Craig Newmark Graduate School of Journalism at CUNY

Angelica Das

Senior Program Associate, Public Square, Democracy Fund

Tim Isgitt

Managing Director, Humanity United

Manami Kano

Philanthropy Consultant, Kano Consulting

Maria Kisumbi

Senior Advisor, Policy and Government Relations, Humanity United

Lauren Pabst

Senior Program Officer, Journalism and Media, MacArthur Foundation

Tracie Powell

Program Officer, Racial Equity in Journalism Fund, Borealis Philanthropy

Karen Rundlet

Director of Journalism, Knight Foundation

Roxann Stafford

Managing Director, The Knight-Lenfest Local News Transformation Fund

Lea Trusty

Program Associate, Public Square, Democracy Fund

Paul Waters

Associate Director, Public Square, Democracy Fund

This letter was updated with new signatories on October 19.