The social sector needs new models for understanding what impact might be possible when systems fall apart. Read the full article at Stanford Social Innovation Review.

Topic: Systems

Looking Forward to the Future of Democracy

The volatility of current events makes one thing clear: Our democracy is vulnerable to disruptions many haven’t even imagined. While we cannot predict the future, we can practice futuring — the creative discipline of tuning into the signals, imagining what’s possible, and choosing paths that lead us toward hope.

In fall 2020, Democracy Fund collaborated with Dot Connector Studio and a diverse group of thinkers on a futuring project called Democracy TBD. Together with our collaborators, we considered how the pandemic, racial unrest, political division, and other concerns might spark a cycle of disruption and reorganization for our democracy. We surfaced key themes — like ongoing political polarization — and identified the potential implications for our democracy.

American democracy was born out of an experimental mindset and radical imaginings; we believe these are still needed for it to survive. For Democracy Fund, this is only the beginning of our futuring venture.

Digital Democracy Initiative Core Story

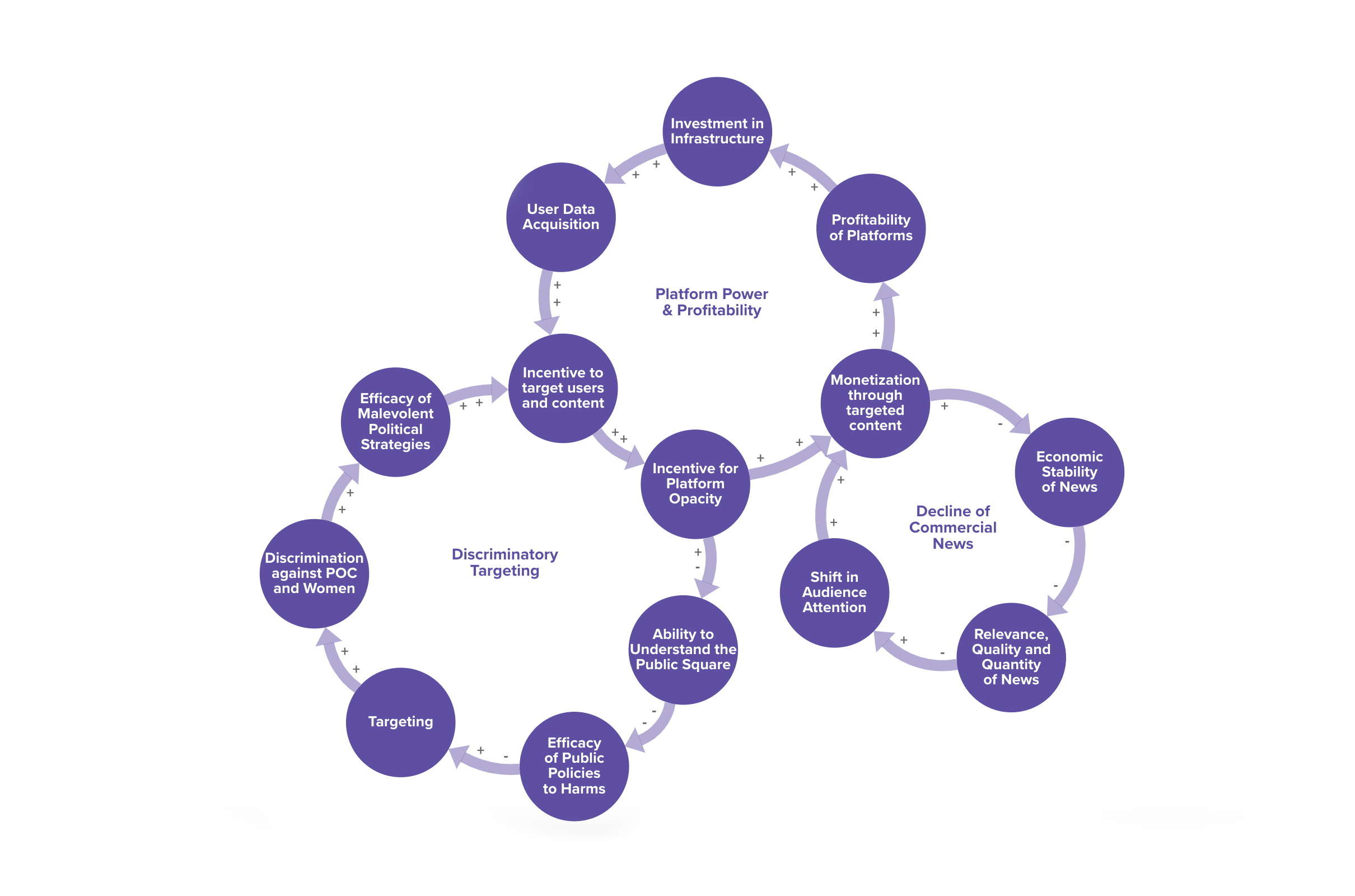

Our democracy is a complex political system made of an intricate web of institutions, interest groups, individual leaders, and citizens that are all connected in countless ways. Every attempt to influence and improve some aspect of this complex system produces a ripple of other reactions. To identify the root causes of problems we want to address, find intervention points, and design strategies to affect positive change, we use a methodology called systems mapping. We create systems maps in collaboration with broad and inclusive sets of stakeholders, and use them to design and then assess our grantmaking strategies. They are intended to provide a shared language, creating new opportunities for dialogue, negotiation, and ideas that can improve the health of our democracy.

This systems map describes how digital tools and technologies have transformed our public square in recent years for better and for worse. The flow of news, information and civic discourse is now largely governed by five major companies: Facebook, Twitter, Google, Microsoft, and Apple. Following numerous high-profile scandals, the public has grown concerned about issues of discrimination, mis/disinformation, online hate and harassment, lack of transparency, voter suppression, and foreign interference in our elections through the platforms. The platforms’ lackluster response to these crises suggests that we need to build a strong movement to force the platforms to become accountable not just to their shareholders, but to the public.

The map consists of three interlocking loops.

- Platform Power & Profitability describes how the platforms have come to dominate digital communications at the expense of the public square’s overall health and transparency.

- Discriminatory Targeting lays out the ways in which platform tools have been used to weaken our democracy, spread hateful content and disinformation, and have exacerbated longstanding racial, economic, and gender inequalities.

- The Decline of Commercial News shows why and how news publishers have been unable to compete with platforms for attention and profits in the digital age, and what the loss of journalism means for the public square.

Adapting Long-term Strategies in Times of Profound Change

This piece was originally published in the Stanford Social Innovation Review.

Over the past few years, foundations have increasingly embraced a systems approach, formulating longer-term strategies designed to solve chronic, complex problems. We value foundations for having strategic patience and being in it for the long haul. But what happens when they carefully craft a set of strategies intended for the long-term, and the context of one or more the interconnected problems they are trying to address changes considerably? Our experience at Democracy Fund, which aims to improve the fundamental health of the American democratic system, provides one example and suggests some lessons for other funders.

My colleagues and I chronicled the systems-thinking journey of Democracy Fund as we went about creating initiatives. After becoming an independent foundation in 2014, we went through a two-year process of carefully mapping the systems we were interested in shifting and then designing robust strategies based on our understanding of the best ways to make change. Our board approved our three long-term initiatives—elections, governance, and the public square—in 2016.

The 2016 election and its aftermath

It would not be an overstatement to say that the context for much of our work shifted considerably in the months leading up to, during, and following the 2016 US presidential election. Our strategies, as initially developed, were not fully prepared to address emerging threats in the landscape of American democracy, including:

- The massive tide of mis- and dis-information

- The undermining of the media as an effective fourth estate

- The scale of cybersecurity risks to the election system

- The violation of long-held democratic norms

- The deepening polarization among the electorate, including the extent to which economics, race, and identity would fuel divisions]

During and after the election, we engaged in a combination of collective angst (“How did we miss this?”) and intentional reflection (“How can we do better?”). We came out of that period of introspection and planning with three clear opportunities for our work that we carried out over the next few months.

- Ramp up our “system sensing” capabilities. We realized we needed to be much more diligent about putting our “ear to the ground” to understand what was going on with the American electorate. Our sister organization, Democracy Fund Voice, was already doing research that explored why many Americans were feeling disconnected and disoriented. Building on those lessons, we founded the Democracy Fund Voter Study Group, a bipartisan collaboration of pollsters and academics that seeks to better understand the views and motivations of the American electorate. It explores public attitudes on urgent questions such as perceptions of authoritarianism, immigration, economics, and political parties. We also ran targeted focus groups and conducted polling around issues of press freedom, government accountability and oversight, and the rule of law. Collectively, these gave us (and the field) insights into the underlying dynamics and voter sentiments that were shaping the democratic landscape.

- Create an opportunistic, context-responsive funding stream. Our long-term initiatives, while highly strategic, did not leave many discretionary resources for needs that arise in the moment. Hence, with support from our board, we launched a series of special projects—time-limited infusions of resources and support to highly salient, timely issues. Our special project on investigative journalism supports and defends the role of a robust, free press in America’s public square. Our special project on fostering a just and inclusive society seeks to protect those whose civil rights and safety seem endangered in this emerging landscape. And finally, our special project on government accountability, transparency, and oversight aims to strengthen the checks and balances that help Americans hold their leaders and government accountable. Taken together, these projects address urgent issues undermining the foundations of our democracy.

- Codify our convictions. As a bipartisan organization, we believe that sustainable solutions require broad buy-in, and we strive to incorporate good ideas wherever they originate. However, in the midst of multiple violations of democratic norms in the heat of the 2016 election, we asked, “Does being bipartisan mean being neutral?” In other words, we questioned whether our positioning prevented us from taking a stance. The answer was a resounding no. But we also felt we needed a point of reference from which to act. We then set about creating a healthy democracy framework that codified our core convictions—a framework that would allow us to take principled positions, speak out when needed, and act by putting our resources to work. The framework articulated a set of beliefs, including the importance of respecting human dignity, the role of checks and balances, the significance of a free press, and the expectations of elected leaders to act with integrity. These beliefs act as a filter for what fits or doesn’t fit our general frame for action.

Lessons for other funders

Based on conversations with other funders, I know our experience is not unique. The field, as a whole, is trying to understand what it means to be strategic at a time of unprecedented change. Below are a few lessons that may be helpful:

- Recognize that “both/and” is the new normal. Rather than see the dynamic between the long-term and the immediate as an either/or, foundations need to adapt a mindset of both/and. The urgent needs are in many ways symptoms of systemic failure, but they do need dedicated responses and resources in the short term. Our attention is our most precious resource, and foundations need to constantly calibrate theirs to make sure it is appropriately focused.

- Go beyond adaptive learning. Notions of adaptive philanthropy—having clear goals, a learning agenda that tracks to those goals, and experimenting along the way—are helpful and did indeed shape our thinking. At the same time, we and other funders must recognize that adaptive learning, by itself, may not be sufficient when the nature of change is profound, rather than incremental. There may be times when we need to take several steps back and examine core assumptions about our work, as Democracy Fund did with our healthy democracy framework, and the McKnight Foundation did with its strategic framework.

- Invest in self-care. This may seem like strange advice in a discussion about strategy, but organizations are made up of people, and people tend to burn out in times of incessant and relentless change. It is important to recognize that we are living in a fraught political environment, and foundation staff, grantees, and partners may need an extra ounce of kindness and grace from others as they carry out their work. This may mean additional capacity building support for grantees, wellness counseling for staff, and an organizational culture that promotes empathy and understanding.

Conclusion

Foundations are unique in the sense that they have the ability to focus on an issue over a considerable period of time. And the recent strides the field has made on systems thinking have ensured that long-term strategies consider the multi-faceted nature of systems we are seeking to shift. However, we are grappling with the question of what happens when long-term thinking bumps up against immediate and acute needs.

In Democracy Fund’s case, building better system-sensing capabilities, creating a context-responsive funding stream, and codifying our convictions have equipped us to better respond to changing context. Our journey is by no means complete and we have a lot to learn, but we hope that our experience gives others—especially foundations wrestling with how to address immediate needs without abandoning their core priorities—an emerging roadmap for moving forward,

How Is Philanthropy Working to Rebuild Trust in the Public Square?

In August, my colleague Srik Gopal wrote about the work Democracy Fund has been doing to understand the contours of trust in democratic institutions from elections to journalism and the public square. We have much more to share from that research and the grant making strategy that it is informing. However, even as we were undertaking that research, Democracy Fund and other foundations were investing in people and projects related to these issues.

For example, the Knight Foundation recently unveiled a new commission on “Trust, Media and Democracy,” which will meet around the country over the next year looking for new ideas and solutions to issues of trust. What follows is a snapshot of some of the efforts underway to combat misinformation, strengthen truthful reporting and create more trusting relationships between people and the press. Later this month I’ll be participating in a series of briefings on trust and misinformation for funders organized by Media Impact Funders in partnership with the Hewlett Foundation and the Rita Allen Foundation.

A version of this piece originally appeared in the May edition of Responsive Philanthropy, the journal of the National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy.

As such, we have to understand that the challenges we face today are not just technological, but also economic, cultural and political. The scholar Danah Boyd has called this an information war that is being shaped by “disconnects in values, relationships and social fabric.” They are fundamentally human struggles and have as much to do with our relationships with each other as our relationship with the media.

Given this complex web of forces, it can be difficult to determine the best role for philanthropy. This is the kind of wicked problem that systems thinking is designed to help untangle. At Democracy Fund, we have invested in systems approaches because they help us develop multi-pronged strategies that reinforce one another in a complicated and dynamic world. Systems thinking helps us see the often hidden and tangled roots of the issues we care about.

In response to these issues some foundations are organizing rapid response grants and programs designed to invest in new ideas and projects. Some donors are investing in investigative journalism and local news to expand the capacity of trustworthy newsrooms. Others are taking a measured approach, adjusting their current grantmaking or planning with their grantees for the ongoing engagement these challenges demand. The reality is that we need both long- and short-term strategies.

For all the concern about “fake news,” there is still a remarkable amount we don’t know about trust, truth and the spread of misinformation online or the impact it has had on politics and public debate. So much news consumption and distribution happens on private platforms whose proprietary data makes it hard for researchers to study.

Defining the Problem Without All the Data

And yet, organizations like the American Press Institute, Engaging News Project, The Trust Project and Trusting News Project as well as a number of academic researchers are testing real-world strategies for building trust and probing the reach and influence of mis- and disinformation.

Foundations should expand their support for research in this area but should do so strategically and in coordination with other foundations to ensure that lessons are being shared and translated into actionable intelligence for the field.

At the start of this year, New Media Ventures launched an open call for media and technology projects from “companies and organizations working to resist fear, lies and hate as well as those focused on rebuilding and using this unprecedented moment of citizen mobilization to shape a better future.” In about a month, they received more than 500 applications, an unprecedented number for them.

Open Calls as a Call to Action

A few days later, the Knight Foundation, Rita Allen Foundation and Democracy Fund announced a prototype fund for “early-stage ideas to improve the flow of accurate information.” That fund received 800 applications in a month. Finally, the International Center for Journalists just launched a“TruthBuzz” contest, funded by the Craig Newmark Foundation.

These open calls are a way for foundations to catalyze energy and surface new ideas, bringing new people and sectors together to tackle the complex challenges related to misinformation.

Trust is forged through relationships, and for many, the long-term work of rebuilding trust in journalism is rooted in fundamentally changing the relationship between the public and the press. For the last few years, foundations like Democracy Fund, Knight Foundation, Rita Allen Foundation and others have been deepening their investments in newsroom community engagement efforts.

Negotiating New Relationships Between Journalists and the Public

Organizations like Hearken, which reorients the reporting process around the curiosity of community members, and the Solutions Journalism Network, which encourages journalists to report on solutions, not just problems, help optimize newsrooms for building trust. The Center for Investigative Reporting, ProPublica and Chalkbeat have also pioneered exciting projects in this space.

Making journalism more responsive to and reflective of its community demands culture change in newsrooms and an emphasis on diversity and inclusion. If we want communities to trust journalism, they have to see themselves and their lived experiences reflected in the reporting. Too often that is still not the case, and foundations can play a vital role in sustaining the ongoing work to renegotiate these relationships.

In December, Facebook announced that it was enlisting fact-checking organizations around the globe to help assess the veracity and accuracy of stories flagged by Facebook users on the platform. Google is working with Duke University’s Reporter’s Lab on how to surface fact checks in their search results and is trying to give more weight to authoritative sources.

Weaving Fact-Checking Into a Platform World

The growth of the fact-checking field in recent years has been fueled by strategic investments from a number of foundations, including Democracy Fund. These investments have helped strengthen the practices and infrastructure for fact-checking making these platform partnerships possible. However, new challenges demand new kinds of fact checking.

Foundations should not wait until the next election to increase support for these efforts. Now is the time to invest in learning and experimentation to make fact-checking work even better, engage an often critical public, and adapt to the new realities we face.

While fact-checkers hone the science of debunking official statements from politicians and pundits, we need to develop new skills for combating the wide array of unofficial and hard-to-source falsehoods that spread online. A leading organization working on these issues is First Draft News, which combines rigorous research with practical hands-on training and technical assistance for newsrooms, universities and the public. (Disclosure: I was one of the founders of First Draft News.)

Cultivating New Skills for Combatting Misinformation

Other efforts include Storyful, Bellingcat, the Atlantic Council’s Digital Forensics Research Lab and On The Media’s “Breaking News Consumer’s Handbook” series.

Most of these efforts work not only with newsrooms, but also human rights organizations, first responders and community groups who are on the front lines of confronting misinformation. Foundations should help connect their grantees to these resources and support First Draft and others to scale up their work in this critical moment.

In April, five foundations and four technology companies launched the News Integrity Initiative at the CUNY Graduate School of Journalism. Designed to advance a new vision for news literacy, this global effort is rooted in a user-first approach to expanding trust in journalism. Today, we the people are the primary distributors of news. As such, it is critical that the public be adept at spotting fakes and debunking falsehoods, and that we cultivate the skills to track a story to its source and the motivation to hold each other accountable.

A New Era for News Literacy

With support from MacArthur, Robert R. McCormick, Knight and other foundations, projects like The News Literacy Project, Center for News Literacy and The LAMP have been working with students for years to address these issues. Similarly, youth media groups like Generation Justice in New Mexico, Free Spirit Media in Chicago and the Transformative Culture Project in Boston, are working with diverse communities on becoming active creators, not just consumers of media. And libraries across the country are hosting workshops and trainings for people of all ages.

In the past, foundations funding health, climate change and racial justice have recognized the need to help people sort fact from fiction. Today, foundations can help expand the field by investing in engaging models of news literacy and supporting efforts to get news and civic literacy into state education standards.

James Madison wrote in an 1822 letter that “A popular Government, without popular information, or the means of acquiring it, is but a Prologue to a Farce or a Tragedy; or, perhaps both.” We are increasingly facing an information ecosystem flooded by misinformation and disinformation being strategically deployed to spread uncertainty and distrust. Those efforts are being amplified by the speed with which information is shared across social media, algorithms tuned for viral views and emotional impact and filter bubbles that increasingly divide us into silos.

Prologue to a Farce or a Tragedy

There is no one-size-fits-all solution to address the challenges of eroding trust and the spread of false and misleading information. The interventions discussed above are largely focused domestically but there is more that can and should be done to confront these issues on the global stage. Foundations and donors should invest in approaches that focus on making change across three interconnected areas: the press, in the public square and social platforms.

Given the diverse strategies foundations can pursue in their response to this moment, it is critical that we work together to share what we are learning, invest strategically in what is working, and put the people most impacted by these issues at the center of our funding.

Tackling Challenges in Election Administration and Voting Using an Ecosystem Approach

Democracy Fund’s Elections Program is excited to share our Election Administration and Voting systems map! The map, which was a collaboration involving advocates, academics, election officials, and policy experts, informs our thinking about American elections and our strategies for improving them. Below, you’ll read about our mapping journey, about potential leveraging opportunities within the system, and a request for your help as we continue to learn.

Though many aspects of the past election cycle were unique, there are ongoing challenges in election administration that pre-date 2016, as well as emerging opportunities for change. We hope that our work in elections will inform and support election officials, policy experts, advocates, peer funders, and most importantly—the American electorate.

Before diving in, our team would like to recognize all our colleagues who provided valuable feedback, and poured their time, energy, and perspectives into pulling this map together. Our collaboration stretched across the political spectrum, which generated robust conversations that inspired us as we created the map and used it to plan our strategy. We extend special thanks to Professor Paul Gronke, who provided support and academic consultation that was vital to the completion of this map.

Mapping the Election System

In December 2014, we convened a group of elections and voting experts to help us more deeply understand the U.S. election system. We began with the framing question, “to understand the election system in the United States, you need to understand…” A core story and key dynamics that drive the election system emerged through several follow up workshops, small group conversations, and internal research.

Because our initiative focuses on election administration, as well as the difficulty of comprehensively describing every aspect of the system, we predicated map construction on two assumptions—that mistakes in election administration:

- Are indicative of actionable problems, for which election officials require strong support to resolve; and

- Have serious downstream impacts on voters, who do not always have the time or knowledge needed to address issues before Election Day.

As shown in our core story, when elections are run ineffectively, there’s high potential for decreased public trust in the system, either because a voter heard about or personally experienced a problem. Sometimes those real or perceived barriers to voting have a deterring effect on voter engagement. These factors—“effective election administration,” “public trust in elections,” and “decision to vote”—appear relatively larger on the map because they are the key factors that drive the system and inform our work.

Low public trust in elections and low turnout increase pressure on lawmakers to change election laws and processes. Sometimes, those proposed changes lead to laws that, when well-implemented and voter-centric, improve elections. However, election administration is uniquely prone to election law gamesmanship, i.e., political actors who attempt to manipulate the rules or pressure officials to act in a partisan fashion. If policy changes are either intended or perceived to influence an election outcome or otherwise shift political power, then such changes can be caught up in a vicious cycle of gamesmanship—ultimately leaving election officials stuck with policies and processes that do not lead to better run elections.

The rest of the map illustrates the key dynamics that drive the core story. Key dynamics appear in 11 cyclical loops, which are:

- Voter Registration

- Election Official Education

- Election Management

- Technology Innovation

- Voting Equipment

- Integrity and Security

- Ease of Voting

- Voter Engagement

- Education About Elections

- Barriers to Voting

- Election Law Gamesmanship

We binned each of the factors (i.e., dots) within these loops into one of four major categories:

- Politics, law, and policy (green),

- Elections process (light blue),

- Voter engagement (yellow), and

- “Other” (orange) for any one factor that does not neatly fit into any of the above categories.

We invite you to take a closer look at our map and its narrative, here and in Kumu – the tool we used to visualize the map. While reading the map, please note that pluses (+) and minuses (-) on connections (i.e., arrows) represent an increase and a decrease of that factor, respectively; the direction of the connections provides more information on the relationship between factors. (For example: when looking at the core story—as effective election administration decreases, public trust in elections decreases.)

From Map to Strategy

Our election and voting process can and should be improved; many election officials and voter advocates are already heading in that direction. After consulting with experts in the field and through much deliberation, we found several bright spots and potential points of leverage in the election system that could avoid political gamesmanship through bipartisan appeal and which present a high potential for impact, including:

- Reducing stress on voter registration systems: States are rapidly adopting online voter registration and are becoming members of the Electronic Registration Information Center. There is also significant momentum around improving registration processes at motor vehicle departments and other state agencies. Improving voter registration systems could potentially result in tens of millions of newly registered, eligible citizens.

- Improving the quality of election planning and execution: The growing community of civic technologists seeking to improve elections presents new opportunities for collaboration. Cost savings generated by new technology allows election officials to solve complex problems with few funds. Improving election processes has the potential to have positive downstream impacts on the voter experience, increasing the public’s confidence in election outcomes.

- Increasing election officials’ capacity to adopt and implement new technology: Adoption and evaluation of tech tools that support election officials are gaining momentum. There is increasing interest among election community leaders in using and iterating these tools. Improving support for election officials using technology could have a transformative effect on the way elections are administered and on the way voters interact with the system, and without feeling overwhelming for the election official.

- Increasing the public’s trust in elections: unsubstantiated allegations of widespread voter fraud are damaging and undermine the legitimacy of those in elected office. To foster trust in the system, voters must, at minimum, have a better understanding of the system’s key security features. Increased attention to security presents an opportunity to educate the public about election processes and to show how their election officials protect the integrity of the ballot. Given the new concerns about attempted interference in our election system by foreign actors, policy and practice must allow for officials’ ability to defend against potential attacks.

It will not be easy to improve the election system, nor will challenges be solved by any one organization alone. We understand that officials, advocates, experts, and voters all play a role in improving and promoting a healthy election system. Now that we have a framework, we can more easily identify where actors and activities occur within the elections and voting ecosystem, and have a better sense of where we should address problems.

How You Can Help

The map reflects our current understanding of the elections system in the United States and we hope that it captures key cyclical patterns that occur at the federal, state, and local levels. Of course, we are not able to capture every aspect of the system; we hope that we can rely on our larger community of stakeholders (you!) to help. As you navigate the map, please feel free to provide us with any feedback, questions, or comments by emailing us at electionsmap@democracyfund.org.

Thanks for viewing! We look forward to hearing from you.

Election Administration and Voting Systems Map

Voting is the foundation of a healthy democracy. Elections are fundamentally about everyday citizens expressing their views and participating in government. Legitimate election outcomes are predicated on a process that is free and fair for all qualified citizens. The American electorate deserves a modern, voter-centric election system that runs efficiently and inspires trust in electoral outcomes.

As we learned during the 2000 presidential election, problems with election administration can have serious ramifications on the public’s perceptions of electoral fairness. More recently, concerns over foreign influence, coupled with unsubstantiated allegations of widespread “rigging” during the 2016 presidential election, called the resiliency of the election system — and the legitimacy of the outcome — into question.

Despite these challenges, we believe that the election system remains resilient. In a time with a renewed spotlight on electoral fairness, and in consideration of the ongoing challenges that states face, the Democracy Fund seeks to better understand our election system’s most salient dynamics. Starting with the framing question, “to understand the election system in the United States, you need to understand…” we used systems thinking to identify three key factors that create pressures for change, both positive and negative: “effective election administration,” “public trust in elections,” and “decision to vote.”

The American election system is decentralized — as long as there is no conflict with federal requirements, localities have a significant amount of flexibility in the way elections are run. Election processes are determined by local, state, and federal requirements; administrative rules; and rapidly changing technology. Since election rules are highly varied among states and local jurisdictions, systems thinking helps us grapple with the complex nature of elections and allows us to find common occurrences that apply to every election.

Improvements to the election system will require legal and administrative changes, technological upgrades, and partnerships between election officials, lawmakers, and other key stakeholders. Many of these stakeholders were invited to participate in the generation and iteration of our Election Administration & Voting systems map. It is our hope that the map reflects our thinking about the election system and serves as a guide for Democracy Fund to do our part to improve the voter experience.

Understanding Our Analysis

Elections are about everyday citizens expressing their views and shaping their government. Effective election administration, high public trust in elections, and high levels of voter engagement are signs of a healthy election system and a healthy democracy. By “effective election administration,” we are referring to a process that balances security with access, and embraces policies that are well-implemented and voter-centric.

Election administration in the United States is ripe for dramatic improvement through common-sense reform. However, election policy is also uniquely prone to political gamesmanship, i.e., political actors may attempt to manipulate the rules in a partisan fashion. Policy changes that are perceived to influence an election outcome or otherwise shift political power will likely perpetuate a vicious cycle of election law gamesmanship. Whether intentional or not, election law gamesmanship ultimately makes it difficult for election officials to administer effective election processes.

Voter Registration

Two main challenges necessitate voter registration reform. First, voters might not understand or be able to easily register to vote. Second, administrators face challenges processing and maintaining accurate voter registration data.

Voter registration is the basis for all election planning. In nearly every state and jurisdiction, eligible citizens may only vote after registering. Registration can also serve as a potential barrier for those who:

- Do not understand the requirements and timing of registration,

- Do not know they are not registered,

- Do not know how or when to update their registration record, or

- Encounter administrative hurdles, e.g., not having the appropriate documents required by the state.

Under federal law, a state’s chief election official must maintain a statewide voter registration list. Registration roll accuracy is vital because election officials must determine voters’ eligibility, assign voters to precincts, and make critical decisions about the type and number of resources that are needed to serve voters, among other things. Because election planning depends so heavily on registration, inaccurate rolls can cause inefficiencies throughout the system, potentially decreasing voter confidence in election outcomes. A bad Election Day experience might even cause some people to stop voting altogether.

List maintenance is an enormous challenge for at least two reasons. First, people are more mobile than ever before and many voters do not update their address at the elections department. Second, the diverse sources of registration forms can lead to errors. Registration forms come from voters, motor vehicles departments, public service agencies, political parties, and third party registration groups. Though many states offer online voter registration, many state agencies and groups still use paper forms. So while handwritten forms offer another option for people to register, they also increase the potential for errors in the state registration rolls.

Election Official Education

As public servants, election officials must possess the technological acumen, public relations expertise, and adaptive decision-making skills essential to navigate our rapidly-changing environment. Most election officials receive regular professional training at the state and county levels. Though many are successfully implementing innovative practices, it is unclear to what extent these training programs create a culture of adaptation in election management.

Because election administration in the United States is decentralized, the availability and rigor of these training programs vary widely by state. Additionally, limited resources and regional cultural dynamics can make knowledge-sharing difficult. Although several tools offering best practices and assistance outside of state training programs exist, it is unclear if election officials effectively know about or access those resources. Furthermore, travel costs and other considerations can hinder networking opportunities for local election officials. Over time, these and other dynamics identified in our systems map can make it more difficult for election officials to maintain high-quality election planning.

Election Management

Election management refers to the decisions and processes for planning and administering elections. Election officials take steps to ensure that Election Day runs smoothly, even in the face of ongoing challenges. Election official capacity to meet voter needs depends not only on available budget, but also on their access to new ideas from professional education and training, use of line management tools and other technology, and their ability to collect and use election data.

Many election officials grapple with budget constraints, which directly impacts their ability to successfully plan and execute voter-centric elections. Resources — financial and otherwise — affect an official’s ability to, for example, purchase reliable voting equipment or offer early voting options. With insufficient resources, voters might experience long lines or an equipment malfunction. These experiences may also cause some voters to lose confidence in the election system.

Technology Innovation

Technology captures a large amount of very useful election data that officials must know how to harness. These data have the potential to provide election officials with key insights into voter behavior and organizational processes. Because elections are subject to a high level of scrutiny, there are also opportunities for officials to use these data transparently for the public’s benefit.

Election technology includes the products of for-profit voting machine vendors, as well as the digital tools created by academics and civic technologists. For many election officials, it is extremely difficult to keep up with the latest innovations. Some jurisdictions may be hindered by the cost of new equipment and some officials might find it risky to try new technologies in high salience elections. Adoption of new election technology is rapid in some respects (e.g., ePollbooks), and very slow in others (e.g., ballot on demand tools), which indicates that more information and education about these resources are required.

Importantly, adoption of new technology may impact voters’ perceptions about elections. First, many Americans are already exposed to the latest technological advances in other areas of their lives and may come to expect the same from election officials. Second, voter confidence in election outcomes is influenced by the voter experience. Lack of innovation or technology that fails could have a negative downstream impact on the voter experience.

Voting Equipment

A handful of for-profit companies build, sell, lease, and service voting equipment for the 10,000 election jurisdictions in the United States. Because elections are relatively low priority when compared to other budgetary considerations, most election jurisdictions will invariably rely on the vendor’s service contract to keep machines running for as long as possible. Reliance on these contracts, episodic purchases or upgrades to voting equipment, and the very limited marketplace for voting machines, have disincentivized major innovation among vendors.

Stories about voting machine failure, whether personal experience or not, can shake voters’ confidence in election outcomes. Continued reliance on service agreements and market stagnation increase the possibility of voting equipment failure or decertification. When reported widely, the impact of a machine malfunction in one jurisdiction can cause a negative ripple effect on the entire system.

Integrity and Security

Election integrity and security are vital components of a healthy system. Election officials create and implement a wide variety of security protocols and procedures, which range from pre-logic and accuracy testing of voting equipment to the post-election canvass. These processes encompass both the physical and electronic security of election materials and data, and are put into place for at least two reasons:

- To ensure that ballots are protected and counted to the fullest extent of the law, and

- To maintain the privacy of qualified individuals’ identifying information, to the extent that the law allows.

There are several advocacy groups focused heavily on either the voter access or election security aspects of election integrity. At the end of the day, election officials must be able to strike a balance: create procedures that maintain system integrity without compromising the rights of voters.

Real threats test the integrity of the American election system. The recent news about unauthorized, unsuccessful attempts to digitally infiltrate statewide voter registration lists have come to the fore and put confidence in our election processes at risk. And while election officials have responded quickly to reduce cybersecurity risks and prevent future attempts at hacking, the high salience nature of these stories drowns out the important work that election officials do, which potentially reduces the public’s trust in elections.

Ease of Voting

In a 2014 report, after determining that voters need more opportunities to cast a ballot, the Presidential Commission on Election Administration recommended that states expand opportunities to vote before Election Day. Early voting periods allow campaigns and advocates to bank their base early so that they can concentrate on fewer voters for Election Day. As campaigns encourage more citizens to cast ballots early, pressure builds on election officials to increase access to early voting.

Currently, 37 states and the District of Columbia allow early in-person voting, no-excuse absentee voting, or both, and three states conduct elections exclusively by mail. Although early voting can reduce the obstacles to engagement for many people, it can also negatively affect voter confidence (in-person voters tend to report higher confidence levels than those who cast their ballots early by mail). Furthermore, as more voting options are made available, the financial, time, and personnel cost of election administration increases.

Voter Engagement

The decision to vote is complex. It is affected by “individual resources” (e.g., education, income, political interest), “social resources” (e.g., civic memberships, church attendance), and the efficacy of voter mobilization by organizations. These complex dynamics, combined with notions of confidence in government, form a tight bundle of social relationships often referred to as social capital. Elections build social capital and enrich and improve civic life. Higher levels of participation can lead to higher trust in government and in others. But at the same time, Americans have become less engaged with civic associations and have less trust in government; as result, they are less likely to vote.

Making voting easier by changing laws, policies, and processes can increase voter turnout, but it’s also important for citizens to think that elections — and government — matter to their daily lives. Voters can get basic public information about elections from multiple sources. However, basic information is not designed to help voters understand why an election matters. Campaigns, advocates, and media give context to the issues or offices on a ballot. The type of election (presidential, primary, state, local) is also key to understanding interest. The perceived importance of the offices and issues up for election are colored by voter attitudes, media attention, and peer pressure, among other factors.

Education About Elections

Making the effort to cast a ballot may seem small, but for many people the personal cost of participation might be high. And while early voting has made voting more convenient, a potential voter must take time and effort to arrive at the polling place, research ballot information, stand in line, and cast the ballot. The closer the election, the more critical basic information about voting becomes. If information is hard to obtain, it is hard to get voters interested in an election.

Citizens might not engage in civic life if they believe that government is hyper-partisan, ineffective, or irrelevant. Those who have a low capacity and tolerance for political debate may ignore competing information about the candidates and issues. Additionally, campaign behavior may make disengaged citizens feel even more disconnected from government and politics. Finally, our research suggests that partisan in-fighting turns people off from participation.

Barriers to Voting

Intentional and unintentional barriers to voting can arise through legal, legislative, and administrative decision making. When critical decisions are before lawmakers, judges, or election officials, it is vital that they weigh the impact those changes could have on discrete groups of voters, especially racial and ethnic minorities who have been subjected to purposeful disenfranchisement. Changes to election and voting laws may also have negative effects on women, persons with disabilities, individuals with language-access needs, residents in rural communities, and members of the overseas and armed services communities.

Litigation is one means of defending voters from the legal and procedural changes that negatively impact voting rights. Legal challenges require courts to evaluate a complex set of facts, laws, and procedures very quickly. In some cases, these suits are settled out of court, with issues partially or wholly alleviated. Even when well intended and especially when suits are brought close to Election Day, litigation and subsequent court decisions may give election administrators little time to make the mandated adjustments and could cause confusion for voters.

Election Law Gamesmanship

Changes to election laws and procedures are often viewed as efforts to game the election system and hurt political opponents. Regardless of actual motivation, the perceived intent of gamesmanship reduces the likelihood of bipartisan cooperation, undermines much-needed modernization efforts, and stalls politically neutral best practices — making bipartisan support for election policy changes more challenging.

New Report Highlights Challenges to Congress’ Capacity to Perform Their Role in Democracy

Imagine having a job that requires you to master complex subject matter thrown at you at a moment’s notice in rapid fashion. Now imagine that you have practically no time, training, or resource support to learn that material with any real depth. Nobody else around the office knows anything about what’s on your plate either to even point you in the right direction. Oh, and you’re using a 10-year-old computer and work practices are such that you’re still literally pushing paper around much of the day.

How would you feel about the job you were doing in that situation? How long would you stay?

Unfortunately, for many congressional staffers, this description is all too apt of their workplace. New research authored by Kathy Goldschmidt of the Congressional Management Foundation (CMF) reveals how dissatisfied congressional staff are with their ability to perform key aspects of their jobs they understand are vital to the function of the institution as a deliberative legislative body. The dysfunction that the public sees in Washington, the report reveals, really is the product of a Congress that lacks the capacity to fulfill its obligations to Americans.

CMF researchers performed a gap analysis of surveys they took of senior-level House and Senate staffers, measuring the distance between how many respondents said they were “very satisfied” with the performance of key aspects of their workplace they deemed “very important” to the effectiveness of their chamber. The largest gaps appeared in the three areas most closely connected to the institution’s ability to develop well-informed public policy and legislation and with Congress’s technological infrastructure to support office needs.

Although more than 80 percent of staffers though it was “very important” for them to have the knowledge, skills, and abilities to support members’ official duties, only 15 percent said they were “very satisfied’ with their chamber’s performance.

CMF found similar yawning gaps in satisfaction with the training, professional development, and other human resource support they needed to execute their duties, access to high-quality nonpartisan policy expertise, and the time and resources members have to understand pending legislation. Just six percent of respondents were “very satisfied” with congressional technological infrastructure.

These findings reflect a decades-long trend by Congress to divest in its own capacity to master legislative subject material. Just last month, more than a hundred members of the U.S. House of Representatives voted to slash funding for the Congressional Budget Office, despite its integral role in the legislative process.

But as the report concludes, opening the funding spigot and hiring more legislative staff alone will not solve the challenges to the resiliency of Congress as a democratic institution.

The Democracy Fund’s Governance Team has taken up ranks with a growing community to push for a more systemic approach to improving the operations and functions of our 240-year-old national legislature struggling to adapt to the forces of modernity. Certainly, Congress can do much more to support its own internal culture of learning and expertise: but civil society has a critical role in rebuilding congressional resiliency, too. Congress has just started to bring the vast technical and subject area know-how that exists outside its marble edifices to assist a process of institutional transformation. The work of establishing trusted modes of communications with constituents in this digital age, meanwhile, barely has begun.

The CMF report performs a critical pathfinding role, illuminating where the places of most dire need within the institution exist. I read it as an optimistic document: congressional staff know that their deepest deficiencies are critically important to the institution’s health. Energy is on the side of reform. The challenge ahead is not to be discouraged by the scale of the problems but to work systemically so that change can build upon itself and ripple through the system.

Mapping the Legislative Ecosystem

Few things about Congress are simple: even different types of information it generates as a legislative body – from bill language and roll call votes, to members’ press releases and statements into the official record – are processed and maintained by a myriad of offices. Over the last half-dozen years, public servants of those offices and citizens invested in open access and easy use of the data Congress produces have gathered annually at the Legislative Data Transparency Conference, hosted by the Committee on House Administration. Originally held as an opportunity for the various stewards of legislative data to discuss collective challenges, in recent years the conference also has become a moment to herald the unappreciated success of the legislative data community in standardizing and releasing datasets that help the American people understand congressional efforts and hold elected representatives accountable.

On June 27, I joined OpenGov Foundation Executive Director Seamus Kraft and Demand Progress Policy Director Daniel Schuman on stage at this year’s conference. Our panel discussed how the legislative data community can use Democracy Fund’s Congress & Public Trust systems map to contextualize its efforts in the broader congressional reform movement.

WATCH: Mapping Congress to Power Meaningful Reform & Innovation

Successes like publishing bill text in machine-readable formats or creating common xml schema are not going to end up on the nightly news. But a proper legislative data infrastructure makes it possible for bill histories and vote records to become evident with a few clicks of a mouse or for instant visualization of how a bill would change existing law. These types of innovations make it easier for members of Congress and their staff and to do their jobs and keep congressional conduct transparent for the electorate. In the broader transformation it encourages, in other words, legislative data reform efforts help strengthen congressional capacity and support a more informed citizenry.

It’s important from a systems perspective to remember that even work on small-scale projects can create ripples of change in a complex environment like Congress. As Schuman reminded the audience, every new dataset that comes online opens possibilities for techies to build new tools that help fill knowledge gaps people within the system can use to solve common challenges.

The panel suggested ways that individual organizations can utilize the systems map to think strategically about their contributions to institutional change. For example, Kraft said that the OpenGov Foundation drilled down on the map in the context of their product design, discovering in the process that constituent engagement was a vitally underserved focus area they could impact with a new project to transform congressional offices’ processing of voicemail and constituent calls.

The systems map also helps remind narrowly-focused communities like the one we addressed Tuesday that their collective efforts also impact the work of similar communities focused on different types of challenges. Washington is full of such groups, whether they focus on government ethics and transparency, the rules and procedures of Congress, of the ways in which advocacy groups make their case to lawmakers. Actions by one community change the dynamics of the system in significant ways for others. The challenge for those across such communities who care about a healthy congressional system is working in concert with one another to amplify efforts.

For our part, our team recently revised our systems map to represent our new thinking on congressional oversight of the Executive Branch. These changes better reflect the importance of government watchdog organizations, transparency and government oversight groups, whistleblowers, the media, and others in holding Congress accountable to its Constitutional responsibility to oversee the conduct of federal offices and the White House.

To learn more about our systems map project, please visit democracyfund.org/congressmap or email us at congressmap@democracyfund.org to sign up for email updates.

Congress and Public Trust Systems Map

Congress’ inability to take up the substantive issues of the day and its constant partisan conflict are eroding what trust remains of the American people in the institution, further undermining their broader faith in government as a whole.

It is vital, therefore, that Congress change itself to become a more capable and responsive legislative body. Just as important, the voices of the public need to be heard through the static of our current shrill political discourse.

These improvements will require changes in behaviors and attitudes by actors inside and outside the congressional system. They will also require significant change to the way Congress currently conducts its legislative business, and a restoration of its internal capacity to form informed public policy. Because of this complexity, we employed systems thinking to map the roots of Congress’ current state.

With input from former members of Congress, Capitol Hill staffers, lobbyists, journalists, and scholars studying Congress, the Democracy Fund has generated an initial map that we hope will provide a holistic picture of congressional dysfunction and improve our understanding of how the institution can better fulfill its obligations to the American people. This work builds from efforts of our partners, the Madison Initiative of the Hewlett Foundation.

A story of dysfunction

The Democracy Fund began this project with a framing question: How is Congress fulfilling or failing to fulfill its obligations to the American people? Early on, we concluded that the institution was largely failing to do so. The broader and more substantive question was, why? What were the most significant dynamics contributing to this dysfunction? And what could be done to address them?

Of course, Congress is not failing completely in its responsibilities. By focusing on dysfunction within the current system, our goal was to produce a document that could help uncover useful intervention points for improving the institution that would not rely on complete systemic changes to the legislative branch or require a wholesale reinvention of American politics.

Core stories within the map

Three interrelated narratives, represented by the red and orange loops on this map, organize our detailed analysis of current congressional dysfunction.

The red loop explores how Congress receives and internalizes a variety of policy requests and how its performance in processing the demands placed upon it affects public satisfaction and trust in the institution.

This core story begins with an observation (in red) that Congress is struggling to keep up with the mounting demands and pressures coming at it from a diverse, wired society. Members are struggling to represent their constituents as they endeavor to process competing policy and political demands. The hyper-partisan political climate in both chambers has greatly weakened the institution’s capacity to function. Weakened congressional capacity further erodes public trust and satisfaction in the institution. This risks driving segments of the public away from political engagement altogether, robbing Congress of different points of view while intensifying the impact of the loudest and shrillest partisan voices it hears. The decline of congressional capacity and the growing dissatisfaction with congressional performance are intensified by the stories contained by the two orange core story loops.

Dissatisfaction, along with important demographic shifts within the two-party system, drives increasing intensity of electoral competition for partisan advantage in Congress. Governing majorities — particularly in the House — rarely have turned over so rapidly in U.S. history as they have in the last 20 years, leading the minority party to consistently focus on the belief that its return to power is just around the corner.

This competitiveness has led the parties to stake out clear ideological differences between one another, forcing their partisan constituencies farther and farther apart philosophically. As the parties and their constituents have fewer ideas in common, hyper-partisan behavior increases within the electorate and among those elected to Congress, winnowing the possibility for compromise and dragging down congressional function. The disengagement of citizens with little appetite for such partisan warfare has intensified hyper-partisanship within the institution.

The narrative captured in this loop helps explain the partisan gridlock that has ground legislative operations in Congress nearly to a halt. But even if its leaders were interested in advancing substantive legislation, dissatisfaction with congressional performance also has affected the institution’s ability to formulate thoughtful policy solutions. The second orange reinforcing core story loop captures this narrative, beginning with the observation that increased public dissatisfaction with Congress has led members to demonize the institution as they try to run against Washington from an insiders’ position. In practical terms, this political trope has led Congress to slash its own appropriations, reducing the size and quality of its staff and legislative support services. These reductions have weakened member and committee offices’ expert capacity to craft policy, increased the influence of outsider experts who often also proffer campaign donations, and further weakened Congress’ ability to represent the will of ordinary citizens.

Supporting loops

The remaining loops on the map describe how other factors in the system intensify these central narratives. They include factors acting inside Congress (light blue) as well as external factors (royal blue).

Political-industrial complex

This loop describes the financial forces in contemporary congressional campaigns that reinforce the intensity of competition for majorities. Increased competition for majorities, along with changes to campaign nance, has driven more and more money into elections. Just as important, the recent increase in portability of campaign funds has effectively nationalized the electoral map, not only for parties’ campaign committees, but also for large- money donors. Nationalization of the electoral map drives greater competition for control of Congress, forcing members to spend an increasing amount of time raising money and developing relationships with donors nationwide.

Rhetoric of permanent campaign

With the increased ideological sorting of parties, party-nominated candidates are more likely to adhere to partisan orthodoxy on major issues. The emphasis on ideological differences between the parties also diminishes the importance of district-specific or event state-specific issues, making elections more likely to be referenda on the positions of either party as a whole. As a result, members have reinforced their commitment to their party’s ideological principles by ramping up media outreach or introducing legislation that stakes out political turf with little hope of becoming law (so-called “messaging legislation”). These efforts increase the ideological sorting of parties taking place broadly among the electorate.

Echo chambers

The increase in the ideological sorting of parties has created a robust and growing marketplace for partisan news and opinion. The reach of these outlets is augmented by the ability of voters to easily share material on social media. Because of this growth in partisan news and social media, congressional offices increasingly interact with audiences who consume information in a partisan echo chamber. In this media environment, offices face a heightened demand to speak directly to consumers of partisan news. This shift in attention reinforces the ideological perspectives of many partisan constituents, as well as members of Congress, and further defines the ideological positions behind a partisan identity.

Ideological influencers

In this section, two intertwined loops explore how the growing prominence of ideological elites intensifies the ideological sorting of parties. Partisan echo chambers have boosted the reach of ideological elites in the marketplace of political ideas. As a result, these elites are in a better position to scold members of Congress for ideological deviance or to champion favorites. Similarly, the ideological sorting of parties has created a fear in many incumbents’ minds that taking (or appearing to take) a moderate stance on issues may invite a primary challenge from a more ideologically committed opponent. This fear leads many incumbents to align themselves with ideological elites or to seek their support, further intensifying the ideological drift of the parties away from the center.

Demands for loyalty

Hyper-partisanship in Congress reinforces party discipline on roll call votes and in setting the legislative agenda. This drive for loyalty increases intraparty conflict as factions within the caucuses argue over the best courses of action to maximize political advantages and to live up to partisan ideals. Members risk being accused of disloyalty — and denied campaign nance resources and leadership positions — for aggressively pursuing policy solutions with members from the other side of the aisle. These penalties diminish the number and quality of bipartisan working relationships and further reinforce hyper-partisan behavior.

This demand for loyalty also is connected to the growing role of party leaders in setting the legislative agenda. As the capacity of Congress to function as a lawmaking institution has fallen because of members’ inability to work together, leadership has taken on more control of the legislative process. Their increase in control can mean fewer opportunities for compromise-seeking members to chart their own policy courses, as their work would unlikely make headway and could generate disciplinary action by their own leaders. Leadership’s weakening of cross-aisle working relationships therefore further reduces the capacity of Congress to legislate effectively.

Weakening of committees

Leadership’s more powerful role further weakens congressional capacity by undermining the power of committees. Whereas committees and subcommittees have historically enjoyed their own staff and significant latitude to develop proposals and seek legislative compromises, autonomy has been reduced and control shifted into the hands of party leadership. This shift has weakened another potential generator of bipartisan cooperation.

Weakening of congressional oversight

As congressional capacity decreases, the White House takes more responsibility for agenda setting. The political linkages between the executive and legislative branches are thereby intensified as congressional leadership calculates moves relative to the success or failure of the presidency. Because of these intensified linkages, congressional perspective on oversight has shifted toward more political ends. When congressional majorities share the party of the president, committee chairs are reluctant to conduct regular oversight hearings for fear of dredging up embarrassing information that may harm the White House politically. When government is divided, congressional leaders are more likely to use oversight as a political weapon against the president, and federal agencies are less likely to share information that committees request in oversight investigations.

As the independence of oversight from partisan politics decreases, so does the number of authentic oversight hearings – even if adequate staff is trained to execute the hearings successfully. These hearings are a crucial venue for effective congressional oversight — without them, overall institutional capacity to examine the conduct of the federal bureaucracy diminishes. Because oversight is a key constitutional responsibility of Congress, the capacity of the institution further suffers. Reduced independence of oversight from partisan politics also negatively impacts the effectiveness of outside watchdog groups, which further diminishes authentic oversight hearings. A more partisan congressional environment encourages some watchdog groups to act in kind, mobilizing only around investigations that can harm political opponents. Increased partisanship in oversight also lessens the ow of information to nonpartisan watchdog groups from Congress, negatively impacting their effectiveness.

Political incentives for authentic oversight

The political and policy linkage of the executive branch to Congress can cut both ways in terms of oversight, however. The melding together of political fortunes of the branches under united-party government has unique consequences. The greater the perception of misconduct by the executive branch, the louder outside political groups and government watchdogs will call for robust investigation of White House conduct, which increases political pressure for committees to do so. Outside groups’ effort and attention drive greater attention to executive branch conduct in the press, further intensifying the pressure on the White House. For Congress, the political cost of appearing complicit with presidential misdeeds can lead to renewed authenticity of oversight, mitigating some of the damage of other negative reinforcing loops.

Interpersonal impact of oversight

The weakening of independent oversight from partisan politics negatively affects bipartisan working relationships in Congress — particularly among the members of various committees whose collaboration on oversight is essential for execution. This breakdown creates a loop that is negative and reinforcing, and further weakens the independence from partisanship.

Gotcha reporting

This set of loops explores the role that traditional inside the Beltway media plays in magnifying congressional dysfunction. With reduced resources, expertise and reporting capacity, and with congressional capacity for policy simultaneously weakening, Capitol Hill journalism has shifted attention toward interpersonal and interparty conflict. This shift in focus and tone has led many member offices to limit reporters’ access in an effort to avoid the game of “gotcha.”

The constriction of information ow to traditional mainstream media outlets — facing their own reduced capacity and expertise — has created an environment in which congressional offices “communicate” with other lawmakers by sending messages through or leaking information to an already resource-starved media. Conflict-driven coverage relies on unnamed sources and lower editing standards, opening journalists up to manipulation by those inside the system. Unattributed comments create a dysfunctional track of communication through the media that can impact the course of negotiations on legislation and undermine the ability of members to negotiate in good faith and reach agreement.

Changes to congressional offices and staff

These loops explore shifts in the professional qualities and experience of Capitol Hill aides caused by the reduction in resources and strategic adjustments in their work.

Fewer resources drive greater turnover in congressional offices. It’s not just about salary: for wonks interested in working on policy, the recent decline in resources also means the best opportunities for professional development may exist outside Congress. Low pay attracts less experienced staff and the mindset that a job on the Hill is simply a means to a higher-paying job elsewhere in Washington. Members are increasingly hiring aides directly from campaigns. With less (or no) congressional experience, such staff tends to be driven more by partisan and ideological motivations and goals than by a desire to master policy or develop legislative expertise. Their presence on congressional staffs, combined with ideological shifts elsewhere in the system, has contributed to an increased focus on ideology across Congress and a reduction in policy expertise.

With declining official budgets, and less legislation being produced, members have found that hiring additional communications staff over policy staff is a more effective choice. This shift toward messaging makes particular strategic sense given leadership’s current dominance over the legislative process. The greater focus on messaging over legislating also addresses — and reinforces — the political needs that arise from the intensification of electoral competition and the ideological sorting of parties.

Intensification of political communications

As described in the primary core story, eroding satisfaction with congressional performance can intensify the demands and pressures placed upon the system. Members of the public who remain engaged do not simply give up on their interests and concerns; they find more aggressive ways to call for action by Congress.

The internet’s power to organize and aggregate many voices at once has changed the nature of advocacy, intensifying the demands and pressures Congress faces. Internet communication has made it cheaper and easier to activate ideologically-focused constituencies and swamp congressional offices with messaging, while keeping these constituencies engaged and active on issues. These new strategies have given rise to advocacy organizations that exist almost entirely online and often are founded around a core ideological perspective rather than the issue areas of traditional mass-membership advocacy groups. Some organizations also exist principally to raise money to underwrite political advertisements. The organizing and communications power of the internet also makes it easier to activate grassroots public participation in responding to congressional action or inaction.

The role of money

Although the map only occasionally mentions the role of money as an explicit factor in the congressional system, money plays a role in many of these factors. The factors directly affected by the influence of money on the system — either through its role in campaign nance, the business of political communication, or lobbying and constituent influence — are denoted by a green halo to help visualize their impact on congressional function and dynamics.