Focus Area: Elections

Meeting the Moment for the Pro-Democracy Movement

Ten years ago, Pierre Omidyar and I launched Democracy Fund and Democracy Fund Voice after a three-year incubation inside Omidyar Network. The world has changed a lot since then, and so have we.

Over the past decade, Democracy Fund and Democracy Fund Voice have committed $425 million in grants to strengthen American democracy. In that time, we have evolved and grown in our understanding of the perils facing our country and the importance of racial justice as fundamental to our work. We believe that achieving an inclusive multiracial democracy means we must fight for our democratic values now — while pursuing transformative changes that can unrig our political system.

As we enter the 2024 election season, the challenges in front of us are sobering. Despite overwhelming evidence of the dangers posed by authoritarians, new Democracy Fund research shows just how easily Americans will accept undemocratic actions if it benefits their side. While our grantees have worked to ensure consequences for those who tried to undermine our free and fair elections in 2020, the authoritarian threat has not subsided.

Today we face a set of challenges that create profound uncertainty about the future of our republic. The pro-democracy field cannot afford to allow ourselves to be overwhelmed by the high stakes or range of threats. We’ve risen to the moment before and we can do so again.

Democracy Fund and Democracy Fund Voice are focused on ensuring the field is prepared and resourced for the challenges that may emerge before, during, and after the 2024 election cycle:

- We are working on protecting free and fair elections by shoring up election administration.

- We’re fighting back against mis- and disinformation.

- We’re strengthening accountability systems for authoritarian abuses that could come in 2025.

- We’re also calling on our peers to join us in making their nonpartisan election-related grants by April, so that groups have the resources they need in time.

While we stand up against urgent threats, we continue to pursue transformative change toward a political system that is open, just, resilient, and trustworthy. This work is complex and challenging, but innovators and advocates continue to make steady progress and real strides toward transformation.

For example, a decade ago, Democracy Fund began responding to warning signs that local journalism was under threat. The sector was seeing layoffs, newsrooms collapsing, racism and sensationalism were all too common, and communities were being left with little or no trustworthy reporting. Together with our grantee partners, however, we saw in this crisis an opportunity for reinvention. We saw the promise of promoting new business models and centering the voices of communities who were never well-served by traditional journalism. Today there is a growing and thriving landscape of non-profit journalism. A tremendous community of news innovators, including our grantees, have created a new way forward for civic journalism. It’s taken years of patient investment to build from a ripple to a wave — but today we see the wave.

This past fall, funders made a new commitment to scale these approaches. Democracy Fund and a coalition of 20 funders announced plans to invest more than $500 million into local news and information over the next five years. We see this as a down payment toward an even more ambitious vision to reimagine the place of local news in the life of communities and our democracy. Local news will never be what it once was, but Democracy Fund grantees have had the vision to rebuild it as something better. The work ahead of us, in journalism and across our democracy, will take more collective action like this.

Exactly what lies at the end of 2024 is uncertain, but with a clear focus on resourcing, mobilizing, and expanding the pro-democracy movement, our field can navigate the year. It is also the time to work with resilience and purpose on advancing the promising ideas that may grow to be the next wave of change for our democracy.

Democracy Fund Welcomes New Leadership to its Board of Directors and Programs

As part of the organization’s ongoing development in service of its new strategy, Democracy Fund is pleased to announce the expansion of its board of directors and organizational leadership.

Three new board members began their two-year term on Tuesday, March 21:

Danielle Allen, professor of public policy, politics, and ethics at Harvard University, director of the Edmond and Lily Safra Center for Ethics, and James Bryant Conant University professor, one of Harvard’s highest honors. She is also founder and president of Partners In Democracy.

Crystal Hayling, executive director of Libra Foundation and a leading advocate for racial justice in philanthropy. During the global pandemic and racial justice uprisings of 2020, she doubled Libra’s grantmaking and launched the Democracy Frontlines Fund.

Sabeel Rahman, associate professor of law at Brooklyn Law School, and a co-founder and co-chair of the Law and Political Economy Project. Previously, Mr. Rahman led the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA) in the Office of Management and Budget and served as the president of Demos.

“I’m honored to welcome our new board members to Democracy Fund. Each joins with invaluable expertise in the pro-democracy movement, a deep commitment to racial justice, and a keen understanding of what it will take to move our democracy toward a more inclusive, just, and trustworthy future,” said Democracy Fund President Joe Goldman.

Goldman also serves on the Democracy Fund board of directors along with board chair Pat Christen and board member Sarah Steven.

As prominent leaders with extensive expertise in efforts to create a more inclusive, multi-racial democracy, these new board members will be important partners in implementing Democracy Fund’s new organizational strategy.

Democracy Fund’s sister organization, Democracy Fund Voice, also announced new appointees to its board of directors: Deepak Bhargava, lecturer in urban studies at the City University of New York, and Robinson Jacobs of Comprehensive Financial Management.

New Programmatic Leadership

Democracy Fund is also pleased to announce Sanjiv Rao as our new managing director of media and movements to oversee our Public Square and Just & Inclusive Society programs. Sanjiv most recently served as a senior equity fellow in the Office of Management Budget in the Executive Office of the President, on assignment from his role as a senior fellow at Race Forward, working to support federal agency action plans to advance racial justice and support for underserved communities. Before that, he completed a nearly decade-long program term at the Ford Foundation, concluding as director of the Civic Engagement and Government program.

Sanjiv joins Lara Flint, managing director of elections and institutions. She is a skilled advocate with more than 20 years of legal, public policy, and government experience, including a decade on Capitol Hill. Lara previously served as director of the Governance program at Democracy Fund. Before joining Democracy Fund in 2017, she served as chief counsel for national security to then-Chairman Patrick Leahy of the Senate Judiciary Committee, where she led the committee’s work on national security, privacy, and technology.

“Together, Sanjiv and Lara will play a critical role in executing Democracy Fund’s new strategy, strengthening the organization’s grantmaking efforts, and positioning more pro-democracy champions for long term transformational work,” said Laura Chambers, Democracy Fund chief operating officer. “As our organization continues to evolve, our new, dynamic leadership will help us pave a path forward in our pursuit to strengthen American democracy. We are excited for what they will enable us to achieve.”

Additionally, Tom Glaisyer has been appointed executive advisor to the president. As one of Democracy Fund’s earliest staff members, Tom built the organization’s Public Square program and most recently oversaw the organization’s programs as managing director. In his new role, he will forge collaborations between Democracy Fund and its peer organizations across The Omidyar Group, as well as work with the organization’s leadership to anticipate and prepare for long-term threats and opportunities.

These changes occur at a pivotal time for the organization, as Democracy Fund nears its tenth anniversary in 2024. We expect our new, dynamic leadership to challenge us, guide us, and help us pave a path forward toward a more inclusive, multiracial democracy.

The State of Election Administration in 2022

In a nation of over 258.3 million eligible voters, election officials’ myriad duties differ from jurisdiction to jurisdiction—small to large, rural to urban—and from voter to voter. Despite these many differences, there are common themes and predictable challenges faced by every official. And of course, every official has experienced unforeseen events and unexpected circumstances that force them to assess, reform, and adapt. As any official will tell you, there is always another election on the horizon.

The Democracy Fund/Reed College Survey of Local Election Officials provides a window into the attitudes, actions, and needs of the public servants who manage US elections. Surveys during the last three election cycles have illustrated the stable features of the system and the way that the challenges of the moment impact the people administering the democratic process.

Local Election Officials

More than half of election officials are elected – 57 percent overall, but in small jurisdictions with fewer than 5,000 registered voters that increases to 67 percent – while 27 percent are appointed, and 15 percent are hired to fill a position. Just over half of these races are partisan and the other half are non-partisan, and the vast majority of elected officials (81 percent) ran uncontested in the general election. The need to attract candidates and talent will only continue to grow as veteran officials leave the field in growing numbers.

In the 2018 survey, officials’ recent experiences with foreign interference in election cybersecurity impacted the complexity of their work. In 2020, the pandemic and extraordinary polarization of the candidates and the electorate created stress and rapid change in methods of voting that election officials had to manage. The 2022 survey illustrates more emergent challenges as election officials report coping with the combinations of mis- and disinformation about elections, violence against election officials, and extreme partisan disparities in the public’s confidence in election results.

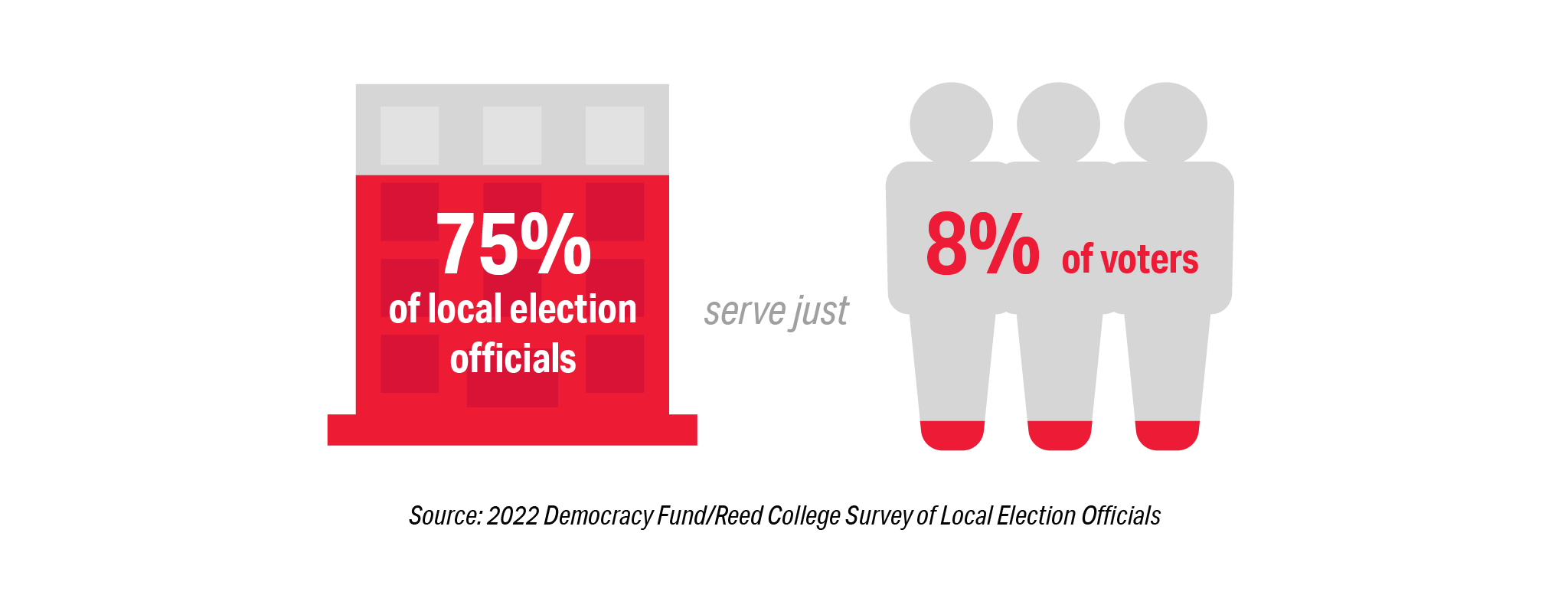

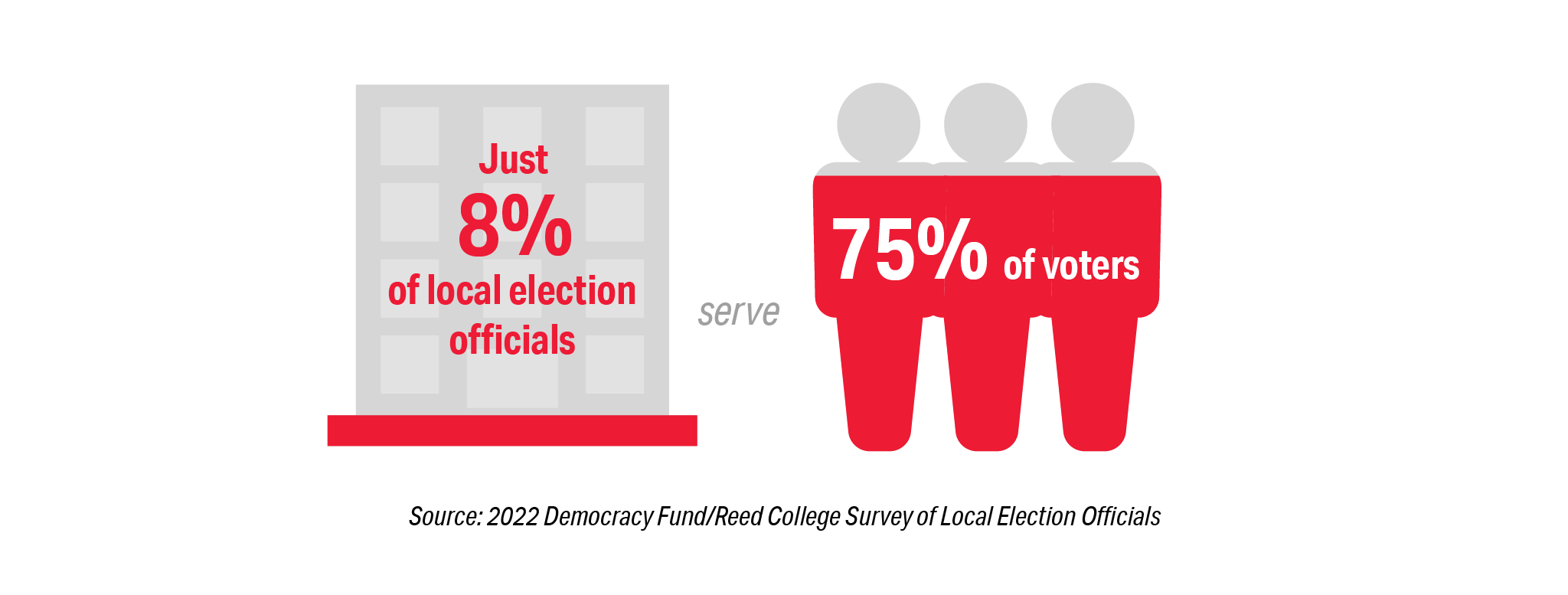

All of this is happening in an environment where the biggest disparity in the election system continues to be geographic. Elections are managed by local jurisdictions and there are tremendous differences between election offices that serve the largest and smallest populations. Seventy-five percent of all offices serve only 8 percent of voters, and 8 percent of our election offices serve 75 percent of voters. This disparity is driven by the fact that the largest 2 percent of offices serve half of the nation’s voters.

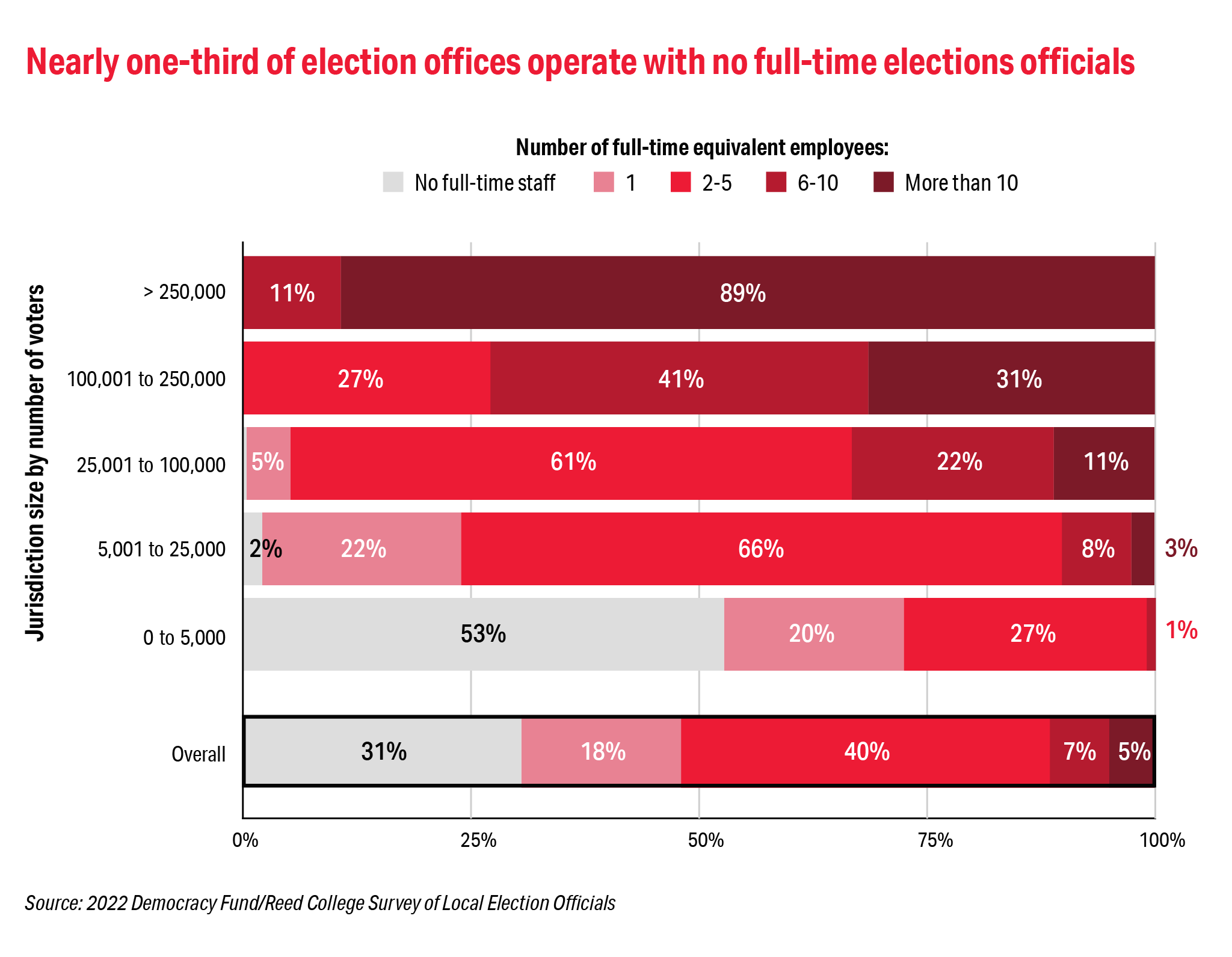

The impact of an increased election-related workload is disproportionally higher on smaller jurisdictions than their counterparts in medium and large jurisdictions. This should not be surprising since one third of all election offices do not have even one full-time employee. In small jurisdictions that serve less than 5,000 voters that number increases to 53 percent. The increased workload for many may have been the result of concerted campaigns to flood election offices with Freedom of Information Act requests around the 2020 election based on conspiracy and conjecture.

Each election cycle, the Democracy Fund/Reed College Local Election Official (LEO) Survey has asked local officials about key aspects of their work including preparedness for the upcoming election, job satisfaction, and training needs for the election officials and members of their staffs.

LEOs retain a commitment to meeting the demands of their jobs and the challenges of finding adequate polling locations and poll workers – especially sufficient bilingual workers and accessible facilities – persist with varying degrees across jurisdiction sizes.

Overall job satisfaction among LEOs remains high, but there are cracks in the veneer. The percentage of LEOs who do not think they can maintain a work/life balance has increased and the percentage who say their workload is reasonable has dropped since 2018.

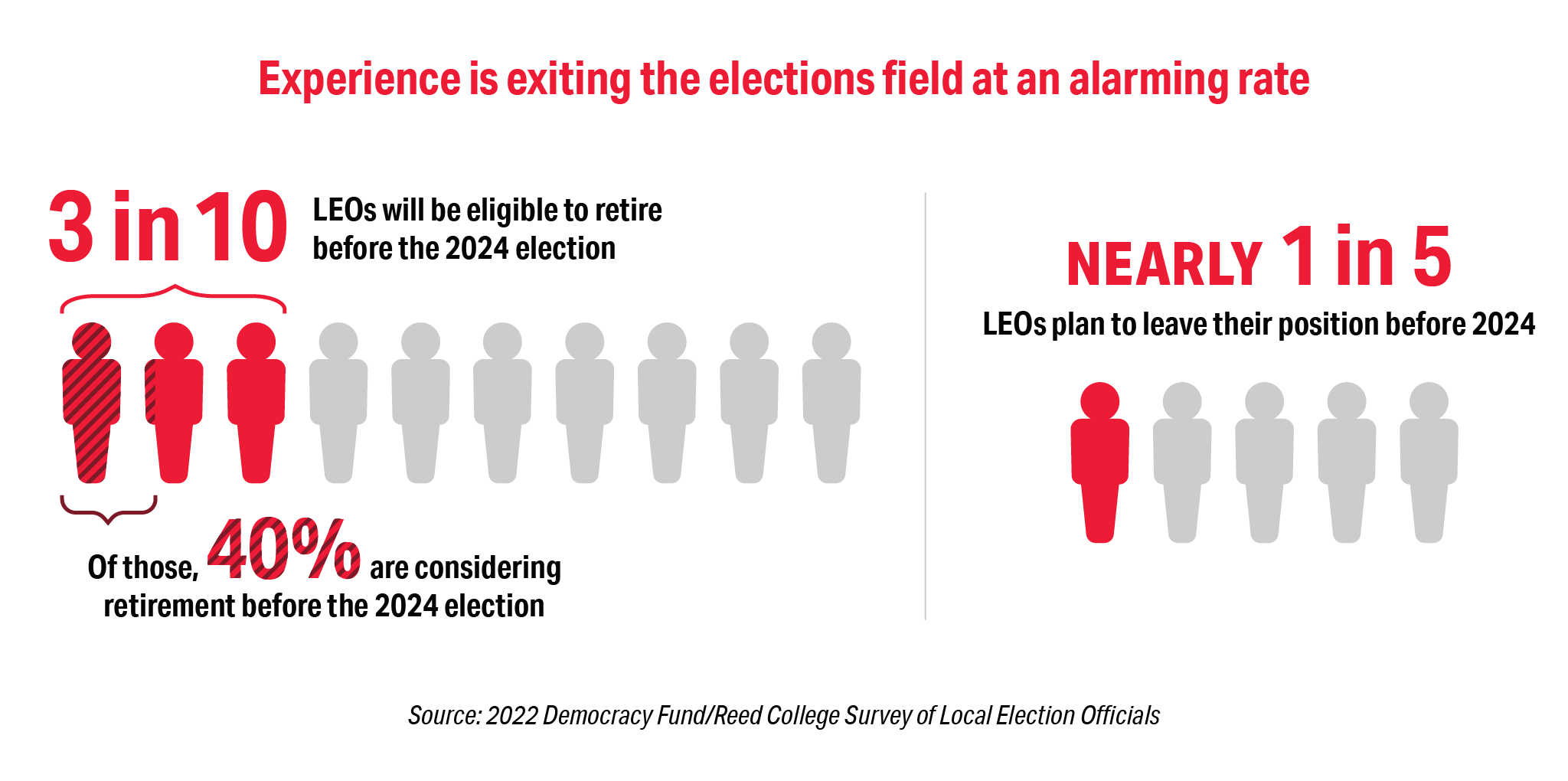

Among the 2022 survey participants, close to one third of the election officials are eligible to retire before the 2024 election—and 39 percent of those eligible plan to do so. Of these respondents, retirement eligibility is the highest reason for leaving the field (51 percent) but “I do not like the changes in my work environment that occurred during and after the November 2020 election” (42 percent) and “I do not enjoy the political environment” (37 percent) followed close behind. For those who are not near retirement age their number one reason for leaving the field was cited as “changes in how elections are administered make the work unsatisfying” (48 percent) and an alarming 28 percent citing that they plan to leave the field based on “concerns about my health or personal safety, aside from COVID concerns.”

Disruption in the Field

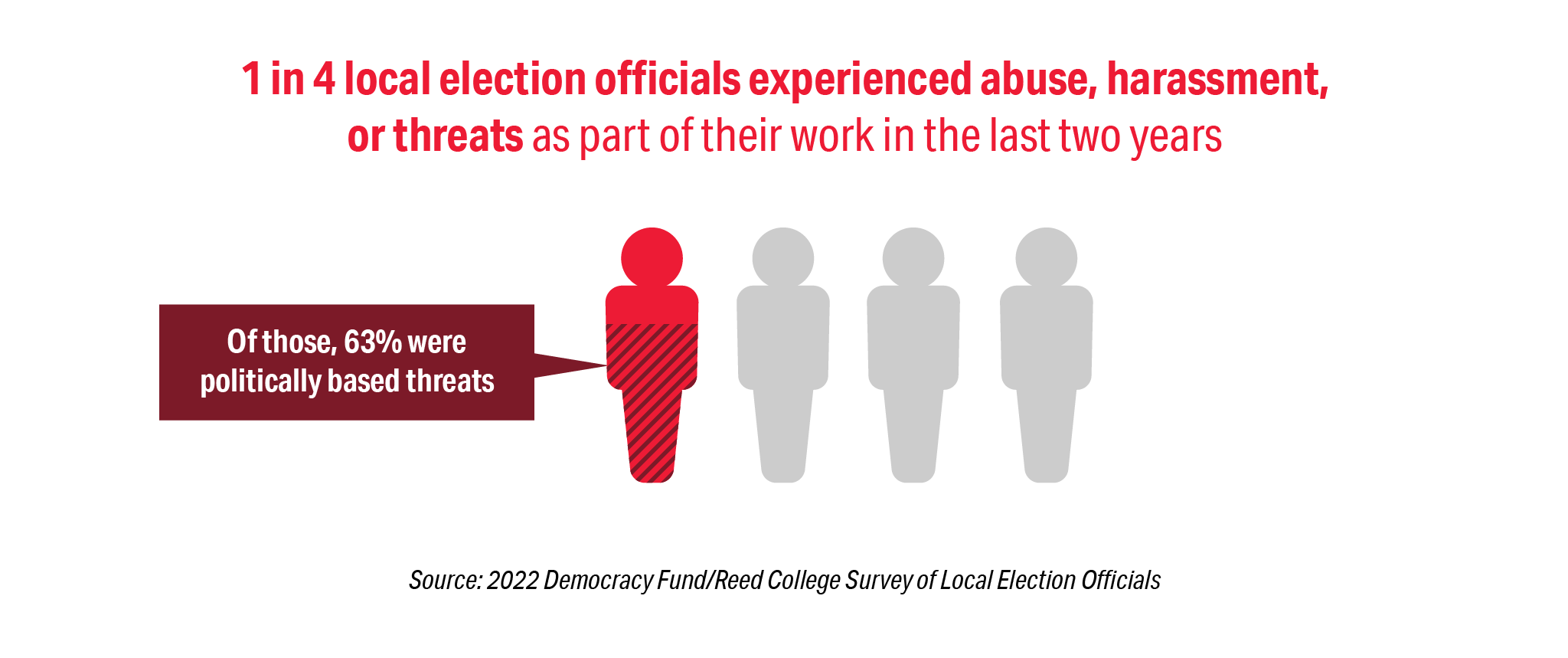

One in four respondents have experienced threats of violence. Officials across all jurisdiction sizes and political affiliations experienced these threats, but the threat environment is much more severe in larger jurisdictions compared to smaller jurisdictions. For example, while 14 percent of LEOs serving jurisdictions with less than 5,000 registered voters told us that they had experienced abuse, harassment, or threats, the percentage increases to two-thirds of LEOs serving in the largest jurisdictions. Similarly, 20 percent of LEOs who told us they were Republicans said they experienced threats, compared to 30 percent of Independents and 34 percent of Democrats. These differences should not disguise the overall result: threats against LEOs are far too real, far too regular, and far too common.

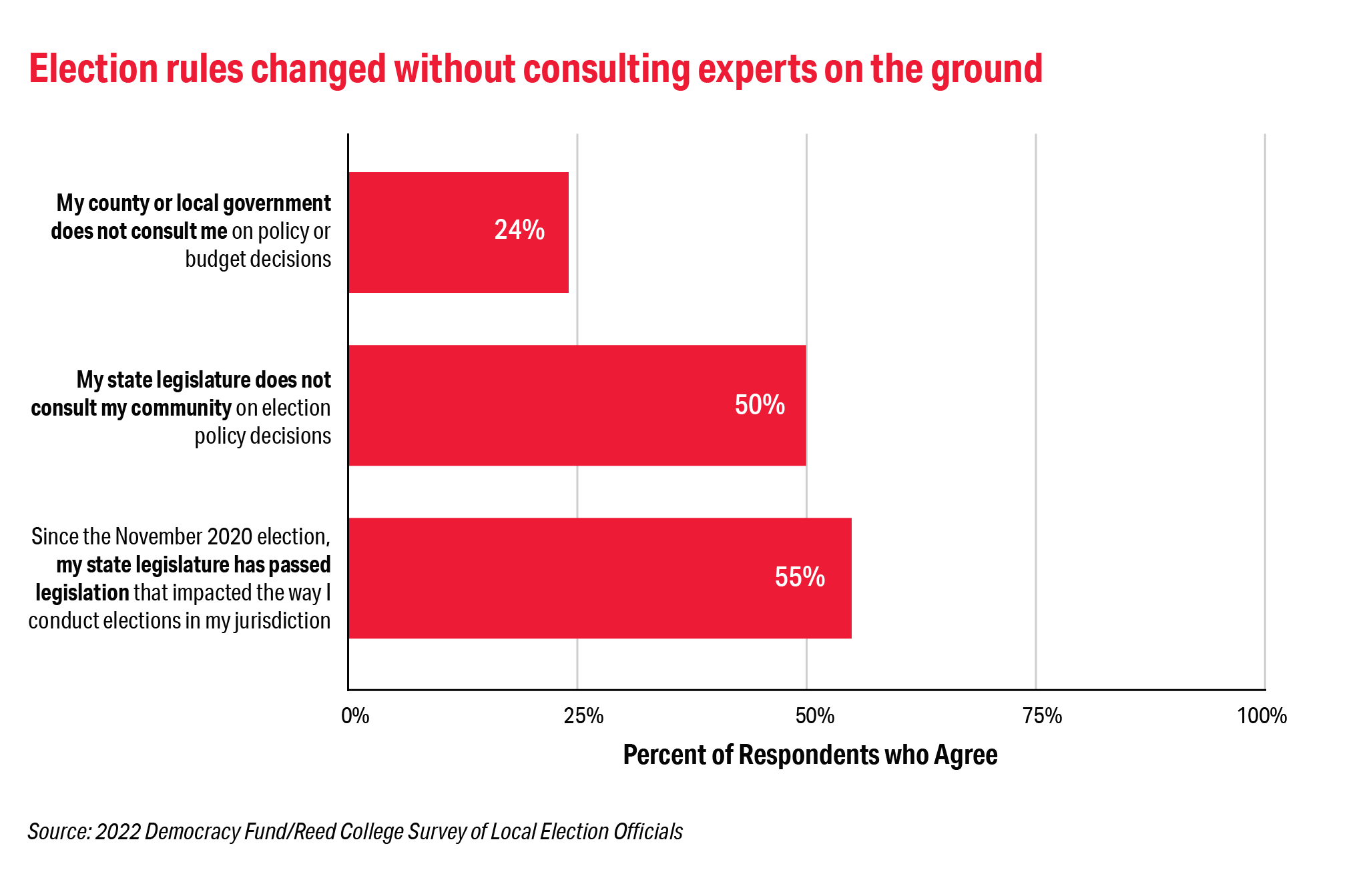

The preponderance of threats targeting election officials are politically based threats. Our 2022 survey showed that 63 percent of threats received were politically motivated. The narrative driving these threats—that the 2020 election was illegitimate and that LEOs were complicit in allowing the election to be stolen–-has manifested in threats to election professionals and their families, and changes to state election laws. More than half (55 percent) of the survey respondents said that they have had legislation passed that impacts how they conduct the election—with 35 percent saying those changes improved election administration and 46 percent saying the new laws did not improve election administration.

The majority – 66 percent – of election officials surveyed this year expressed concern about threats and harassment. When asked how seriously various organizations take the threats to election officials, 43 percent said that their state’s chief election official (in most states, the secretary of state) takes the threats “very seriously.” However, LEOs felt that others took the threats far less seriously: only 27 percent for local law enforcement, 25 percent for federal law enforcement, 17 percent for the state legislature and for the national media, 14 percent for the local media, and 12 percent for the U.S. Congress.

About the Survey and Interviews

The 2022 survey of local election officials was a self-administered web and hardcopy survey conducted from June 21 to September 22, 2022. This study used a LEO sample collected by the team, with a sampling frame based in part on national lists of local election officials and the sizes of their jurisdictions. From this frame, the team drew a sample of 3,118 LEOs, sampling jurisdictions in proportion to the number of registered voters they serve and targeting the chief election official in each jurisdiction to complete the survey. A total of 912 LEOs completed the survey, including 652 surveys completed via web (71 percent) and 260 (29 percent) completed via hardcopy with an overall response rate of 30 percent.

Survey findings are often presented by jurisdiction size to understand differences in experiences.

- Fifty-seven percent of local election officials serve in jurisdictions of 5,000 or fewer voters.

- Twenty-seven percent serve in jurisdictions of 5,001 to 25,000 voters.

- Ten percent serve in jurisdictions of 25,001 to 75,000 voters.

- Six percent serve in jurisdictions of more than 75,000 voters.

While most officials serve in small jurisdictions, the vast majority of voters live in large jurisdictions — over 70 percent of voters live in jurisdictions with more than 75,000 voters and are served by only 500 officials. It’s important to consider the possible differences in scale, responsibility, and resources between different jurisdiction sizes when interpreting results from any survey of this population. Where overall results are presented, they are weighted to ensure that means can be generalized to local election officials nationwide. Further information about the sampling and weighting process is available at the Reed College Elections & Voting Information Center’s project website.

Explore additional 2022 content and learn more about the Democracy Fund/Reed College Survey of Local Election Officials through Reed College’s Elections & Voting Information Center. Prior publications from the survey series are also available below.

Introducing Our New Elections & Voting Strategy

In April 2022, Democracy Fund announced a new organizational strategy with a commitment to investing in the power and leadership of communities of color to strengthen and expand the pro-democracy movement, and undermine those who threaten the ideal of our inclusive, multi-racial democracy.

The U.S. voting system was not designed for an inclusive, multi-racial democracy and has always de-valued certain communities, including communities of color, people with disabilities, low-income citizens, and those with intersecting marginalized identities. As a result, people of color face a voting system that continues to be rigged against their participation and power. This flawed design is accompanied by an election administration system long underfunded and weakened by disinformation peddled by an authoritarian movement. False allegations of voter fraud have increased mistrust of election processes and outcomes, led to violent threats against local election officials, and provided a pretext for state legislators to try to seize control of election outcomes.

With these challenges in mind, the Elections & Voting program took a step back to review the past six years of investments and design a new five-year strategy that meets the moment. We seek an election system that consistently produces trusted results, fairly represents the will of the majority of voters, and reflects equitable participation—especially among communities of color. This new strategy builds on the invaluable expertise, accountability, and advice of the many grantees, partners, and leaders we have worked with over the years, all of whom helped inform the direction of this new strategy and to whom we are deeply grateful.

Supporting free, fair, and equitable elections

Our refreshed Elections & Voting program envisions a democracy where people of color hold equal power to influence election outcomes and build a fully representative and participatory democracy. The current election infrastructure needs to function effectively and impartially. As we work towards these goals, we must also reimagine the system to center the voters that have been historically marginalized and oppressed.

To support this vision, we are investing in two areas of work:

- Resilient Elections to strengthen the election infrastructure so it is less vulnerable to election sabotage and election-related violence; and

- Voting Power to focus on equitable participation, voice, and power for people for color.

These two initiatives are built on several assumptions about how Democracy Fund can contribute to the elections and voting field, and where our investments can complement work that is happening on the ground and through other funding partners:

- We believe that robust election administration and election administrators are the last line of defense against authoritarianism. Over the past seven years, we have supported trainings, tools, convenings, and research to professionalize the field of election administration. We will now shift our focus to combatting the politicization of the profession through stable funding and staffing for election administration. When election administrators are well-funded and well-trained, they can expand access to voting and prevent attempts at election sabotage.

- Communities must have the power they need to elect leaders who represent their interests and influence government to be responsive to their needs. Organizers working in communities of color often lack year-round funding to build organizational capacity and conduct essential organizing that would enable sustained political power. Grassroots organizing that centers communities of color needs year-round support that allows them to build sustained momentum for participation in civic life, issue advocacy, and elections.

- More transformative changes are necessary to equalize voters’ power and address the fairness and legitimacy of the election system. Even when people successfully vote, anti-majoritarian structures can reduce their voting power based on where they live. Until we unrig the election system, it is impossible to describe our political system as representing the will of the majority. While we pursue these structural changes, we must ensure voting rights continue to expand.

Some changes you will see in our elections funding

After six years of investments and experimentation, we have taken a close look at our strategy and adjusted to meet both the moment and the needs of the field. Many grantees and partners contributed to our learning by participating in evaluations of the Voter Centric Election Administration and Election Security portfolios, and in our strategy planning process. A few shifts emerged from those reflections, including:

- We will deepen our support for state and local organizing groups that are building power in their communities, particularly communities of color, to engage and connect individuals in their communities, empowering them to impact policy when they participate in civic life.

- We will recenter our support for voting rights work at the national level to better complement grassroots organizing and state election policy and advocacy.

- We will invest less in tools and trainings for election officials while supporting election administration in new ways, with an emphasis on how to properly fund and staff election infrastructure, infuse a racial justice lens into election administration, and disincentivize leaders from undermining election results.

- In partnership with our Governance Program, we will move away from incremental changes and toward long-term structural changes in our democracy that support representative and equitable majority rule.

Looking ahead to the next five years

We are incredibly proud of and grateful for the important work our grantees and partners have led over the past six years. We will continue to champion the field and are committed to a responsible shift as we build toward an inclusive, multi-racial democracy.

As we prepare for the strategy launch in 2023, we will continue to learn, adapt, and grapple with several outstanding questions. We will partner with other funders to strengthen elections and ensure equitable voter participation. We will share more information and updates on our website about our work, and we welcome your feedback.

You can expect to see similar updates from our other programs as other organizational strategy decisions are finalized.

What We Learned from Evaluating the Impact of Our Election Security and Confidence Investments

In the fall of 2021, Democracy Fund commissioned an evaluation of our Election Security and Confidence portfolio – the major focus of the Elections & Voting Program’s Trust in Elections strategy – to summarize our investments, activities, and impact and help us make informed decisions about future investments. Here, we reflect on the history of our election security work and share key findings from the evaluation. For a deeper dive, we invite you to read the full report.

History of the Election Security & Confidence Portfolio

The 2016 U.S. Presidential Election was a turning point for election security following attempts by foreign actors, namely Russian, Chinese, and Iranian groups, to disrupt the election with cyber-attacks. After the election, as information surfaced about how foreign actors scanned – and in a few cases gained entry into – several state and local election networks, it became clear that election security was now a national security concern. In response to these events, the Democracy Fund Elections & Voting Program added a body of work in 2017 to focus on improving security and confidence in our elections. With an emphasis on election security, this portfolio aimed to fortify the election system to prevent further foreign interference and counter cybersecurity threats by investing in tools and training for election officials. As part of these efforts, we also launched the Election Validation Project, which focused on expanding the use of post-election audits, and Democracy Fund Voice supported coalitions that advocated for, and secured, federal funding for elections in three straight years – 2018, 2019, and 2020 – which was the first funding for elections since the passage of HAVA in 2000.

The Elections & Voting Program’s initial landscaping and research led to the development of four core areas for grantmaking to prevent election interference based on the threats posed by foreign actors and vulnerable security infrastructure. These core grantmaking areas included:

- Fortifying the field with workable solutions and best practices

- Empowering election officials to advocate for funding to strengthen election cybersecurity

- Researching verification practices and resiliency efforts

- Public messaging on the legitimate risks to election systems

Evaluating the Portfolio’s Impact

An evaluation of the portfolio’s impact, conducted by Fernandez Advisors, focused on identifying the impact, growth, and sustainability of our investments to improve both election security and confidence in election outcomes. The report found that our investments in election security resources and tools that increased the capacity of state and local election administrators to identify and manage security threats were among the most valuable. In particular, government agency partners noted the critical role that Democracy Fund played by acting quickly and early to take the financial risks necessary to develop and pilot new election security resources (e.g., trainings, tools, technical assistance, and playbooks), which were eventually adapted by local, state, and federal government agencies once the proof of concept had been established.

Our early investments in election cybersecurity contributed to the successful execution of the 2020 election. These investments in enhancing election cybersecurity through training and tools and the push for additional federal funding for elections helped create the conditions for what the U.S Department of Homeland Security called, “one of the most secure elections in history.”

Summary of Findings & Key Takeaways

Despite our work on election security and cybersecurity, public trust in the election system is dangerously low. When we started our work in election security, we believed that investing in election cybersecurity would protect the system from foreign interference, which would lead to increased public trust in elections. The first part of the hypothesis proved accurate—states and the federal government have adopted many of our grantees’ election cybersecurity training and tools, freeing election officials to turn their attention to other issues in the system. However, hyperpartisanship and threats of authoritarianism have further reduced public trust in elections and – in ways that were simultaneously unexpected and should have been anticipated – exposed new elections vulnerabilities including viral mis-and dis-information, the spread of unproven ballot review techniques, and attacks on election officials.

When we began investing in election security, it was still a young field with few philanthropic players. Democracy Fund played a role in catalyzing new approaches to improving election security, many of which are now embedded in the election system and the work of election officials. The 2016 election was a wake-up call that exposed the security vulnerabilities of our election system, and the system responded by shoring up the infrastructure. We are proud to have played a role in that initial response, and still believe that a resilient system is essential to ensuring free, fair, and equitable elections in this country.

Reflection on the Impact of Investing in Voter Centric Election Administration

From its inception, Democracy Fund has invested in organizations supporting election administration. We believe that well-functioning election operations are a core component of a healthy election system. At the end of 2021, we commissioned an independent evaluation of the Elections & Voting Program’s Voter Centric Election Administration portfolio to review how our theory of change was executed and how the election system has shifted. Here, we reflect on the findings from that evaluation and invite you to read the full report.

Voter Centric Election Administration Portfolio History

The landscape of election administration in 2014 is a far cry from what we experience today. At that time, the findings of the Bipartisan Presidential Commission on Election Administration were widely praised and pointed the way toward evidence-based solutions to election challenges – such as long lines at the polls and errors on voter lists – that made use of developments in technology. Election administration has always been complicated, especially in the highly-decentralized U.S. system. However from 2014-2016, the field experienced clarity of purpose and a relatively-uncontentious bipartisan consensus on best practices to move the field forward.

In this context, Democracy Fund developed a theory of change that focused on two needs of the field:

- Strong networks of election administrators for knowledge-sharing across and within states

- Innovative practices and technology designed for election administrators to use.

To meet the first need, we identified the leaders of state election administrator associations and hosted convenings with them twice a year in a “train the trainer” model, whereby they would learn best-in-class practices to take back to their state associations of election officials. For the second need, we invested in a wide range of civic technology tools, research, and guides developed by civil society organizations that could be used by administrators to better serve voters. Our goal was to scale and spread practices that would improve the voting experience nationwide.

Evaluation of the Portfolio’s Impact

An evaluation of the portfolio’s impact, conducted by Fernandez Advisors, focused on the ways that election officials at the state and local level have engaged in Democracy Fund’s network convenings and used tools, training, and resources in which we have invested. The report found that investing in tools and resources for election administrators helped the field adapt to shifts in voter expectations for online services and new voting methods. Our grantees’ programs helped to improve the design of election websites and ballots, helped administrators adapt to early voting and mail voting policies, and helped voters learn where to find a polling place or ballot drop box easily and accurately. These are just a few examples of the ways our grantees supported administrators’ efforts to serve voters.

This portfolio was especially well-timed to meet the unusual needs of the 2020 election when many states rapidly adjusted their voting policies and practices to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic. Many states offered voters more flexibility to vote early at home or at voter centers in order to avoid crowds at Election Day polling places. These states could not have rapidly adopted new voting methods without following the examples of states that had spent years innovating and experimenting with flexible voting practices. Democracy Fund grantees were instrumental in helping states learn quickly from these examples because they had documented implementation processes and offered technical assistance.

While network-building, tools, and research have been instrumental in improving election administration, the failure of local and state governments to adequately resource election offices remains a significant problem. Significant and ongoing technology changes (such as online voter registration and ballot tracking) present adoption challenges for many election administrators and their staff due to both the lack of funding for technology investments and maintenance and the difficulty covering the range of expertise needed with the very small staffs that manage elections in all but the largest jurisdictions. For example, election officials interviewed for the evaluation report that they do not have the capacity to counter growing mis- and disinformation targeted toward voters.

The job of managing elections has grown increasing complex as the field faces new challenges. Local election officials must be experts in many areas: human resources, information technology, direct mail processing, public relations, cybersecurity, and more. Most election officials are managing this load with little staff capacity. In the 2020 Democracy Fund/Reed College Survey of Local Election Officials, over half of respondents said they work in an office with just one or two staff members who may not even be full-time. Participants in Democracy Fund’s state association convenings praised the information and opportunity to share knowledge and resources with peers from other states and bring ideas back to their colleagues. However, limited staff capacity and urgent demands makes it difficult for many officials to spend time adopting new practices.

Summary of Findings & Key Takeaways

When Democracy Fund began investing in civil society organizations focused on election administration, it was still a young field, with limited philanthropic investments supporting the work. We used a systems and complexity approach to analyze the needs of the field and identify the gaps and leverage points that could improve the health of election administration. We played a role in catalyzing new nonprofit organizations that support election officials and in funding emerging election sciences research. The COVID-19 pandemic upended the 2020 primary elections and made evident the importance of well-resourced and well-functioning election administration. In response, the field of organizations supporting election administration scaled up as more donors began funding this work. Even as the context shifts over time and the field adapts, strong election administration is essential to the health of a just and equitable election system.

Language Access for Voters Summit 2021

Removing Language Barriers from the Voting Process

Democracy Fund’s Language Access for Voters Summit is an annual event that aims to remove language barriers from the voting process. The 2021 convening was held Dec. 13-14, 2021, following the Dec. 8th release of the Census Bureau’s new Section 203 language determinations under the Voting Rights Act—which provide language assistance in U.S. elections.

To help election officials navigate and implement the necessary changes, the agenda included discussions with local, state and federal election officials, voting rights advocates, and translation experts. Participants shared pragmatic ideas, tools, and best practices for providing language assistance—focusing officials’ immediate needs in the lead-up to the 2022 midterm elections.

Celebrating the Diversity of Languages in the United States

The two-day event featured a collection of speaker-submitted videos in Armenian, Bengali, Dine’ (Navajo), English, Korean, Mandarin, Spanish, and Yup’ik. These represent a small sample of the languages election officials provide voter assistance for across the United States.

Speakers read the 2020 Presidential Election ballot in various languages from their jurisdictions, highlighted the critical value of language and culture integration in formal settings like polling places, and shared personal stories of how language access has played a role in their own life or someone they love.

The topics, presentations, materials and resources for each day of the Dec. 2021 summit can be viewed and downloaded below.Paths Forward: Lessons in Supporting Local Election Administration and Officials

Part of “Stewards of Democracy,” a series on findings from the 2020 Democracy Fund/Reed College Survey of Local Election Officials

In the wake of a historically competitive and challenging election, election administration and administrators continue to be flashpoints of political conflict. We want to provide a forward-looking, proactive agenda to sustain this critical part of our democracy and to support the people who serve in more than 8,000 voting jurisdictions nationwide.

For the past six weeks, we have been posting the results of the 2020 Democracy Fund/Reed College Survey of Local Election Officials as part of a “Stewards of Democracy” project. In this final post, we reflect on top takeaways from the 2020 survey and identify paths forward to support and advance the professional community of local election officials.

Here we identify key areas we believe should be a focus for state and local officials and their allies in the policy and research communities. For each, we describe what we have learned from the research as well as where we know we still have a lot to learn — critical questions that call for further experimentation and evidence.

Sustainability Advancement

What we have learned

Local election officials are a community invested with the responsibility of maintaining a piece of critical national infrastructure and administering elections for nearly 240 million eligible voters, yet they report chronic underfunding, a stressful work environment, and rapid and sometimes unexpected policy changes. Local election officials tell us that state and federal lawmakers seldom consult with them when contemplating changes in election administration.

It is vital to identify sustainable budget paths so that local election officials are not constantly faced with new and changing mandates without the resources to meet them. Local election officials are experts and should be consulted as key stakeholders in discussions of the budgets that impact their capacity, as well as legislative and policy decisions related to election administration.

Opportunities for experimentation

Adequate budgets don’t completely solve for the stress and unpredictability of election work. Sustainability also depends on ensuring sufficient and capable staff, which merits attention to recruitment, training, and retention.

Our survey results highlight the importance of professional development and training for election officials. Most officials have access to training when they begin their careers and even more receive ongoing training, but there is variation in officials’ perceptions of how effective that training is. For example, local election officials from the largest jurisdictions are the least satisfied with the effectiveness of their training.

This indicates an opportunity for differentiation in the way training is designed and delivered. To do this well, we need more experimentation in the types of training programs that are offered to election officials and the way those trainings are tailored to the needs of different jurisdictions. Experimentation would allow us to collect new evidence about the kinds of training programs that work best for a diverse and heterogeneous elections administration community.

Where we need more research and learning

The Democracy Fund/Reed College Survey of Local Election Officials provides data on the career backgrounds of the chief local election officials, how long they stay in the field, as well as their job satisfaction and what motivates them to continue doing this work. But we lack data on the staff in local election offices. This would be harder data to gather in a systematic and generalizable way, as our survey does with respect to chief officials, but studying elections office staff would fill in a missing part of the story on diversity, retention, and institutional knowledge in the profession.

Related, we know very little about the recruitment strategies and pipelines used by local election officials to attract staff, what kind of movement occurs across jurisdictions, and whether there are successful diversity initiatives that can serve as object lessons for the elections administration community. As we learn more about diversity in the field, we will have an opportunity to observe how diversity impacts the attitudes and practices of election administrators.

We have heard much this year about a wave of retirements, but we actually know next to nothing about historical rates of retirement and turnover. This makes it impossible to know if we are experiencing a brain drain or just a typical spike that occurs after a presidential year.

And while 60 percent of local election officials across the country are elected to their positions (rather than hired), we know almost nothing about how the elective path operates, and how much turnover is a result of election losses.

Networks and Community

What we have learned

Networks, both formal and informal, and “community” were mentioned again and again in responses to our survey and in our in-depth interviews as ways that local election officials learn, adapt, and maintain resilience in the face of change.

We are convinced that there is a substantial added value to regular state and regional association meetings and venues for professional development, such as Election Center and the election administration program at the University of Minnesota’s Hubert H. Humphrey School of Public Affairs. Not only do local election officials learn in these venues, but they also connect and build support networks. States and localities need to provide budgetary support or other mechanisms so that all election officials, not just those from larger and well-funded jurisdictions, can attend regular training and regional and national gatherings.

Opportunities for experimentation

While we know that networks and community are important, we need to learn more about what structures, events, and learning opportunities are cost-effective and add the most value.

State associations are highly rated as sources of information by most of our survey respondents, but these associations operate very differently from state to state. This variation provides an opportunity to learn how different ways of organizing and creating communities of local election officials produce different levels of engagement and satisfaction among members.

Our survey responses demonstrate that officials in smaller jurisdictions are far less likely than those in medium and large jurisdictions to attend a regional or national gathering of election administrators. Some national programs — such as the ELECTricity, a newsletter run by the Center for Tech and Civic Life — gear their information and outreach toward officials in small and medium jurisdictions. As these programs mature, and new networks are developed, there will be an opportunity to learn about the tactics that bring these officials into the community and how information is shared across the field.

Where we need more research and learning

Interviews with local officials indicate that many of these public servants are connected to other professional networks outside of the elections field. Only 61 percent of local election officials — and 46 percent of those in the smallest jurisdictions — say that elections make up the majority of their workload. Even those who spend most of their time on elections often have other responsibilities, like administering courts, maintaining public records, and issuing marriage licenses. These duties connect them to other functions of their local government and other state and national networks. There is an opportunity to understand how trends in other sectors of local government may impact the work and culture of local election administration.

Voter-Centric Practices

What we have learned

The 2014 report of the Presidential Commission on Election Administration highlighted the importance of a “voter-centric” service orientation among election officials. Respondents to our surveys expressed overwhelming support for a voter-centric approach. Officials, without respect to jurisdiction size, embraced voter education and outreach as part of their jobs. This is good from a customer service perspective and also from a democracy perspective.

But there are barriers to such voter-centric practices: The most commonly cited among these is insufficient budgets for voter outreach. Local election officials must be able to meet voters where they are — whether through print materials, media advertisements, or engagement on social media — and these efforts take time and resources, and may require new skill sets.

Opportunities for experimentation

Our surveys show that some pro-voter policies, such as voter registration modernization, are more likely to be supported by officials who have experienced those policies. This may mean that local election officials who have experience with effective policies can be “champions” to others in the community who have less experience.

However, we don’t know how attitude change occurs among local election officials. Our finding about officials supporting a policy with which they have experience may reflect learning that happens through interactions with a policy — or, it may be acceptance. For example, officials in states that do not currently have a policy may simply be resistant to change, while officials in states that have already implemented a policy have already adapted to the change and accepted a new norm.

Where we need more research and learning

In our post about local election officials’ perspectives on election policy and practice, we noted that the opinions of these officials show some of the same partisan patterns that are observed in the general public. What we don’t know is why these patterns persist in a community of experts that presumably should be more resistant to misinformation and false claims.

More research needs to be done to understand the underpinnings of local election official attitudes toward election administration at a local, state, and national level, and how the structure of beliefs can impact the ethos of election administration. We also know very little about who are the trusted communicators within the community, whether fellow local election officials, state officials, national taskforces, academics, or advocates. Understanding who can best convey information to these local officials is a critical element in advancing a voter-centric approach.

While there is much to explore and learn about the field of local election officials, what we know already points to important ways we can better support the essential work they do in service to democracy and the voting public in their communities.

We encourage fellow researchers, policymakers, and others who care about representative government to be part of this journey of inquiry, knowledge-sharing, and reform. And just like legislators, the research and advocacy communities must engage local election officials in an ongoing and systematic way to ensure we’re asking the right questions and surfacing valuable insights. Local election officials have a critical vantage point, and their voices and expertise should always be part of the conversation.

Pursuing Diversity and Representation Among Local Election Officials

Part of “Stewards of Democracy,” a series on findings from the 2020 Democracy Fund/Reed College Survey of Local Election Officials

With growing recognition of the importance of diversity, equity, and inclusion, organizations across many economic and government sectors have been re-examining the makeup of their teams. Diversity has known benefits to decision making and innovation, and in the administration of a representative government, it is arguably essential to carrying out the values of, as well as building trust and engagement in, a diverse constituency. The representative bureaucracy model, for example, argues that with diversity in the workplace, the public is better represented in administrative decisions. As the American population becomes increasingly multiracial and multiethnic, a governmental discipline whose workforce does not reflect the country’s diversity may indicate that it is constrained for some reason in its appeal or its recruitment pipeline. Related, a lack of diversity in an area of public service raises ethical concerns about whether all Americans have genuine access to that office.

In this post, we present information on diversity in the local election community, focusing primarily on the demographic categories of gender and race/ethnicity. It will surprise few familiar with this community to learn that the average local election official is white and female and that this description has not changed in some time. We suggest some possible explanations for this enduring demographic profile and also spotlight some of the nuances of a complex election system that could challenge efforts to increase its diversity. To take just one example, over half of local election officials are elected to their positions, as are other local officials, so candidate recruitment and voter choice also shape these demographics. Some jurisdictions require that candidates for this role reside in the local area, further limiting the pool of potential candidates.

Finally, there is an important caveat to our findings. Our survey focuses on the single official in charge of election administration within each jurisdiction. We know nothing about the composition of their staffs, which may be more diverse and may, in medium and larger offices, be the public’s main point of contact. From other research, we know a bit more about the racial makeup of poll workers, and that having more poll workers of the same races as voters can improve voter confidence. Interactions with staff and volunteers in the election process who better reflect local diversity may reduce some concerns about representation and enhance legitimacy and confidence.

There is much more to learn. In the final section of this post, we identify some outstanding questions about staff, mobility, and recruitment as important research areas for the future.

A Little-Changing Demographic Makeup

Who are the professionals doing the day-to-day work of running American elections? As we touched on in a preceding post, local election officials are not a population that mirrors the American public. The average local election official is far more likely to be white, a woman, and over age 50 than the general public, or even the voting-eligible public, which skews whiter and older.

The 2020 Democracy Fund/Reed College Survey of Local Election Officials found that almost 75 percent of these officials are over age 50, 80 percent are women, and over 90 percent are white (and non-Hispanic). Almost half had a college degree or even further education, and 44 percent identified as Republican — compared to 33 percent who identified as Democrat and 22 percent who described themselves as Independent (among the 72 percent of respondents who shared any party identification). Only 45 percent make more than $50,000 a year, and 60 percent are elected to their positions.

Before diving into this post’s exploration of gender and race/ethnicity diversity in particular, it’s helpful to understand the demographic stability among local election officials over the past 15 years, as well as a few areas where we see changes.

To do this, we look to three years of our own survey data and that of three surveys from the mid-2000s conducted by the Congressional Research Service (CRS). While changes observed over time can provide important information about developments in the community of local election officials, we warn against overinterpreting small changes in consecutive surveys, which may be due to sampling variability rather than to actual demographic shifts.

With this in mind, we see notable patterns since 2004. First, there is almost no movement in the racial diversity of chief local election officials. With the exception of our survey in 2020, all other mentioned surveys found that about 95 percent of officials were white. There is also minimal change in the proportion who are elected to their position, female, and Republican (or conservative, in the CRS surveys).

The patterns of race and partisanship are in part explained by the decentralized and federalized nature of election administration and the jurisdictions where local election officials come from. While local election officials as a collective do not reflect the diversity of our nation as a whole, they do tend to be more representative of their jurisdictions.

Where we do see notable changes are in age, education levels, and pay rates. In 2020, 74 percent of local election officials are over age 50, compared to 62 percent in 2008. In 2020 dollars, over 60 percent of local election officials were earning more than $50,000 in 2008 compared to just 45 percent now; apparently, their salaries have not kept pace with inflation. Finally, formal education is on the rise. Half of local election officials in our most recent survey reported having a college degree, compared to only 40 percent in 2004.

The race and partisanship of local election officials changed little over six years of surveys

| Demographic | 2004 | 2006 | 2008 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 75% | 77% | 76% | 85% | 83% | 81% |

| White and non-Hispanic | 94% | 95% | 94% | 95% | 94% | 90% |

| College | 40% | 41% | 44% | 46% | 51% | 50% |

| $50,000 or more* | 53% | 61% | 63% | 43% | 46% | 45% |

| 50 or older | 63% | 62% | 62% | 77% | 74% | 74% |

| Republican† | 51% | 47% | 44% | — | 43% | 44% |

| Elected | 65% | 58% | 53% | — | 58% | 57% |

*CRS surveys reported salaries greater than $40,000. Due to inflation, $40,000 in 2006 is approximately $50,000 in 2019.

†CRS surveys reported whether respondents considered themselves to have a conservative ideology, rather than asking about a partisan identification.

Women and Local Election Administration

When we look across the entire U.S. political landscape, we find durable patterns of under-representation of women in public roles. Recent research shows that women currently hold 27 percent of U.S. Congressional seats, 31 percent of state legislature seats, and 30 percent of statewide elected offices, and only 32 of the 100 largest U.S. cities have women serving as mayor. According to 2019 Equal Employment Opportunity Commission data, only 42 percent of county or local officials and administrators are women.

Yet, among local election officials, over 80 percent are women. Why do we see such a different gender composition of local election officials, more than half of whom are elected to their posts, compared to other elected and appointed office holders? There are at least three possible explanations.

First, election work may be filtered by gender in ways similar to other offices in government. For example, a national survey of municipal clerks found an even higher proportion of female clerks (90 percent) than we found in our survey of local election officials. Meanwhile, women make up only 1 percent of sheriffs in the U.S. Even district school boards, which are often perceived as more aligned with women’s interests, have just 44 percent of their seats held by women. Election administration has increasingly become a complex administrative occupation with a diverse skill set. But elections work may have been traditionally viewed as a more clerical role, particularly the registration component. Women may have been directed toward or been more willing to accept positions in election administration. We also note that, historically, some of the more important roles in the conduct and adjudication of elections has been assigned to roles dominated by men, such as sheriff or judge. These patterns may account for the historical and current gender balance of the profession.

A second possibility is a gatekeeping effect among local party leaders combined with the structures that help candidates win elections. In this scenario, women would be differentially allowed “through the gate” to run as local election officials, possibly because elections work is unlikely to translate into higher office. As a potentially related point of reference, our survey asked local election officials if they have an interest in running for elected office (different from their current role, if elected). Overall, only 11 percent indicated they were interested, a number that drops to 9 percent among only female respondents. We lack good comparative data on other local elected offices to conclude that these totals are high or low and whether gatekeeping is going on.

Third, elections work may be sought out by women and less so by men for some reason. It could be that elections administration, especially in smaller offices, offers flexibility that supports a better balance between work and responsibilities at home, which other studies report still fall disproportionally to women in American society. While this may seem to be a surprising notion to local election officials who have just completed an incredibly time-consuming election year, women who responded to our survey were somewhat more likely than men to say that they can balance work and home priorities. Of note, women in larger offices were more likely to tell us that work-life balance was a problem than were women in smaller offices. What we are seeing in these findings may not be a preference among women, but rather a signal that they are more often forced to balance priorities because of fewer career options or cultural norms and expectations.

Gender Differences by Jurisdiction Size

The responsibilities of a local election official vary greatly by the size of the jurisdiction, and not surprisingly, so does the “average” local election official. Those in larger jurisdictions are significantly more likely to be men, non-white, college educated, paid more than $50,000 a year, Democrats or Independents, and appointed to their positions than those in smaller jurisdictions.

Local election officials in larger jurisdictions are more likely to be male, less likely to be white

| Jurisdiction by number of voters | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic | Overall | 0 to 5,000 | 5,001 to 25,000 | 25,001 to 100,000 | 100,001 to 250,000 | >250,000 |

| Female | 81% | 84% | 85% | 69% | 65% | 47% |

| White and non–Hispanic | 90% | 90% | 91% | 89% | 93% | 80% |

| College | 50% | 43% | 55% | 58% | 77% | 82% |

| $50,000 or more | 45% | 23% | 69% | 80% | 98% | 95% |

| 50 or older | 74% | 77% | 70% | 66% | 68% | 61% |

| Republican | 44% | 44% | 50% | 42% | 30% | 17% |

| Elected | 57% | 64% | 54% | 36% | 32% | 18% |

Being the chief elections officer in a larger jurisdiction often has more prestige. It often requires more steps up the ladder or winning what is likely a more competitive and expensive election — all of which may influence the gender of those chosen or self-selecting for such a position. Large-jurisdiction positions are also more likely to involve stresses that challenge work-life balance. Indeed, local officials serving in larger jurisdictions were less positive on the question of balancing work and home priorities.

We see that female local election officials also, on average, earn less than their male counterparts, but these averages may be driven at least in part by jurisdiction characteristics. That is to say, the observed pay differences between men and women may be a function of differential pay by jurisdiction size combined with men’s greater likelihood to serve in larger, better-paying jurisdictions.

Despite this disparity, a majority of local election officials, male and female, told us that they were satisfied with their pay. Women were slightly more likely to raise concerns about pay, but not markedly so.

Women are over-represented overall in our data — and in any survey of local election officials — primarily because of the number of small jurisdictions. It may be that women find the role attractive in these smaller jurisdictions because it is more likely to be part time, supporting work-life balance. It may also be that the nature of the work in a small jurisdiction is perceived to be more appropriate for women through the lens of traditional gender roles, as misguided and outdated as these perceptions may be. Perceptions that operate within thousands of counties and municipalities nationwide would have a powerful effect.

This brings us to a concern: If work-life balance is a key factor in women’s participation as local election officials, threats to that balance could cause a shift in gender composition. The 2020 election created some cracks in the veneer of job satisfaction. If this continues, the cost/benefit calculation could shift, and so could the demographics of the local election community.

“I would recommend [becoming a local election official to others] … I think as long as you have a good understanding of what you’re heading, and what you’re in for, and you have a plan for that, you can have a life balance with family and friends and work. You need to have a plan for that. Then yeah, I would still recommend it.”

– LOCAL ELECTION OFFICIAL, OCTOBER 2020

Race, Ethnicity, and Representative Bureaucracy

Next we explore racial and ethnic under-representation. Approximately 90 percent of local election officials are white and non-Hispanic. That is substantially more than the proportion of white, non-Hispanic people within the U.S. citizen voting age population, according to data from the 2020 Congressional Election Survey (CES). This difference persists even when we compare local election officials to other state and local officials and administrators. Just under 78 percent of state and local officials and administrators across the country are white according to 2019 U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission data.

Local election officials are disproportionately white when compared to the general population

| Demographic | Proportion of local election official population | Proportion of U.S. public (CES, 18+) |

|---|---|---|

| Female | 81% | 52% |

| White and non-Hispanic | 90% | 69% |

| College | 50% | 41% |

| $50,000 or more | 45% | 51% (family) |

| 50 or older | 74% | 49% |

| Republican | 44% | 40% |

| Elected | 57% | — |

Drawing any conclusions about the reasons for these patterns is a challenge for our study because there are so few non-white respondents in our survey. In the subsequent figures, we have pooled the three years of the Democracy Fund/Reed College Survey of Local Election Officials so as to make some comparisons. We also use “white” to refer to the white and non-Hispanic population.

As a first cut, it’s important to recognize that a vast majority (70 percent) of local election jurisdictions have a citizen voting-age population that is over 90 percent white, according to the most recent American Community Survey. Three-quarters of the smallest jurisdictions have voting age populations that are 93 percent or more white, while 50 percent of the largest jurisdiction have populations that are 65 percent or less white. As a point of comparison, the citizen voting age population in the United States overall is 68 percent white.

The reason these numbers come out the way they do is that non-white voters in the United States are relatively concentrated in metropolitan areas and certain states and regions. To illustrate how this works, we randomly selected one voter from each jurisdiction to be a local election official. The result was that our hypothetical workforce of local election officials was still 88 percent white — nearly the same as the 90 percent that we observed in our survey.

The federalized and decentralized nature of election administration (and many other governmental functions) combined with some jurisdictions’ requirements that election official candidates be local residents creates a structural barrier to a more diverse and nationally representative population of local election officials. Efforts to diversify this field may require extra emphasis on recruiting job applicants for staff positions, leadership positions, and candidates from outside the jurisdiction. What we don’t know — and where we think more research is necessary — is how these structural barriers impact local government more generally, and whether and how some local governmental agencies have overcome these barriers.

If we flip our lens and look from the perspective of voters, the situation appears a bit different. Our survey, combined with Census data, shows that non-white voters are somewhat more likely to be served by non-white local election officials.

The majority of white local election officials serve predominantly white jurisdictions. Black local election officials serve a much more racially and ethnically diverse population. Because of small numbers, we combined local election officials in other racial categories (including Native American, Asian American, and Hawaiian or Pacific Islander) and find they too serve a more diverse population. The starkest under-representation in our data is among Hispanic local election officials: We find so few that we are unable to compare these officials with jurisdiction populations.

The size of the jurisdiction once again appears to drive much of these dynamics. Smaller jurisdictions are less likely to have significant populations of non-white voters — and are also more likely to be served by white local election officials.

The overall population of local election officials is significantly more racially homogenous than the voting age population, but local election officials who are not white do serve more diverse populations. Here our survey sheds further light: When we asked if election officials “should work to reduce demographic disparities in voter turnout,” 80 percent to 90 percent of non-white local election officials responded in the affirmative — almost twice as high as white local election officials asked the same question.

For Further Research

As we have described, understanding diversity and enhancing representation among local election officials and their staffs is a complex undertaking. There are many potential reasons for the findings we report here, and further research is needed to reveal complexities and patterns more completely, to understand the reasons behind them, and identify productive steps. We look forward to engaging the practitioner and research community on these questions in the months and years ahead.

We are limited in our ability to investigate some of the potential reasons for the gender and racial disparities we found due to the limited number of officials who are non-white overall and across jurisdiction size categories, but more broadly, due to the inherent limits of survey sampling for a population of 8,000 officials spread across states, counties, and townships and municipalities. Qualitative research involving focus groups and in-depth interviews may be necessary to probe how current officials, those who appoint them, and even those who vote for them, think about the role of a local election official as compared to other local offices.

One complexity we confront in this post is whether or not the overrepresentation of women in local election administration is a good thing, given the traditional underrepresentation of women in positions of power, especially in elective offices, or whether it indicates that women are being channeled to an area of local governmental work that has been historically undervalued and underfunded. Our suspicions, based on our data and other patterns of gender representation in local government more broadly, is that both are somewhat true. There is some evidence that job mobility is lower for women than for men in the election community. Among the local election officials we surveyed who serve in jurisdictions with greater than 100,000 registered voters, 45 percent of men said they have worked in another election jurisdiction, while only 20 percent of women answer similarly. Overall, 18 percent of men say they have worked in more than one jurisdiction versus 13 percent of women. It remains important for further research to explore if these differences result from barriers to upward mobility, filtering by gender, or other factors.

Also with respect to gender, we believe future research should focus on understanding the personal experiences and pathways for local election officials across their careers. While our study is informed by various theories on why women are over-represented in this field, interviews and discussions with local election officials could better explore the dynamics that result in a role overwhelmingly served by women. Turning to race and ethnicity, as noted, our research is focused on the person holding the chief local election official position. While the individual in this role can be influential, we also know that the race and ethnicity of the rest of a local government office staff matter. Further research on the composition of local election office staff and volunteers could better detail the diversity and inclusion of these offices, as well as voter experience.

We were able to show that non-white officials are more likely to be serving in communities with higher percentages of non-white voters, but the still-high level of homogeneity indicates that the elections community, especially in smaller jurisdictions, has too narrow of a recruitment pipeline. Describing the career pipeline, highlighting successful efforts that have been made in expanding recruitment pools, and understanding who constitutes the pool of staff and elections officials of the future are all fertile areas for research.

If the elections community seeks strategies for encouraging diversity in its ranks, it will need to wrestle with the multiple paths that people take to assuming this role. A heavy reliance on elections as a selection method in the smallest jurisdictions puts a damper on hiring-based methods for promoting diversity in a profession, and efforts to bolster diversity may require coordination with former elected positions and political parties (if the races are partisan).

Efforts to expand and diversify the pipeline for service in local election administration will need to take into account substantial structural barriers due to the federalized and decentralized nature of American election administration and the significant gaps in pay, prestige, budgets, and administrative powers between small and large jurisdictions. We know from conversations with officials that state recruitment rules or residency requirements may be one barrier. But we do not know the steps local election offices take to broaden their recruitment for all positions, and if diversity and inclusion is something they focus on in these hiring practices. Related, larger jurisdictions are well positioned to hire an internal candidate like a deputy director who has been “training up” through the department for several years, or to run nationwide recruitment searches for new officials. Still, the vast majority of jurisdictions are not running national-scale job searches for an open position.

In a previous post, we more deeply discussed the age of local election officials, which is another important aspect of their demographic makeup. These professionals are older as a group than they were even 15 years ago, while at the same time being better educated yet earning comparatively less. Age and pay satisfaction are two things that can cause local election officials to leave the profession. How do decreases in compensation, especially in combination with the increase in qualifications that we also see, affect who sticks with the job or moves on? What is, in fact, the “normal” rate of retirement of officials after a presidential election, and how does the rate of retirement in 2020 compare? Further research pursuing these questions will fuel a robust dialogue about what the future of local election administration should look like in the United States.

There is much yet to learn about how recruitment and advancement in election administration helps or hinders diversity. Our 2020 survey findings point to challenges here, as well as potential opportunities. This is just the beginning of the data-driven story, and we hope to see future research engage these questions.

The authors wish to thank Bridgett A. King, associate professor of political science at Auburn University, for her feedback on this research.