Part of “Stewards of Democracy,” a series on findings from the 2020 Democracy Fund/Reed College Survey of Local Election Officials

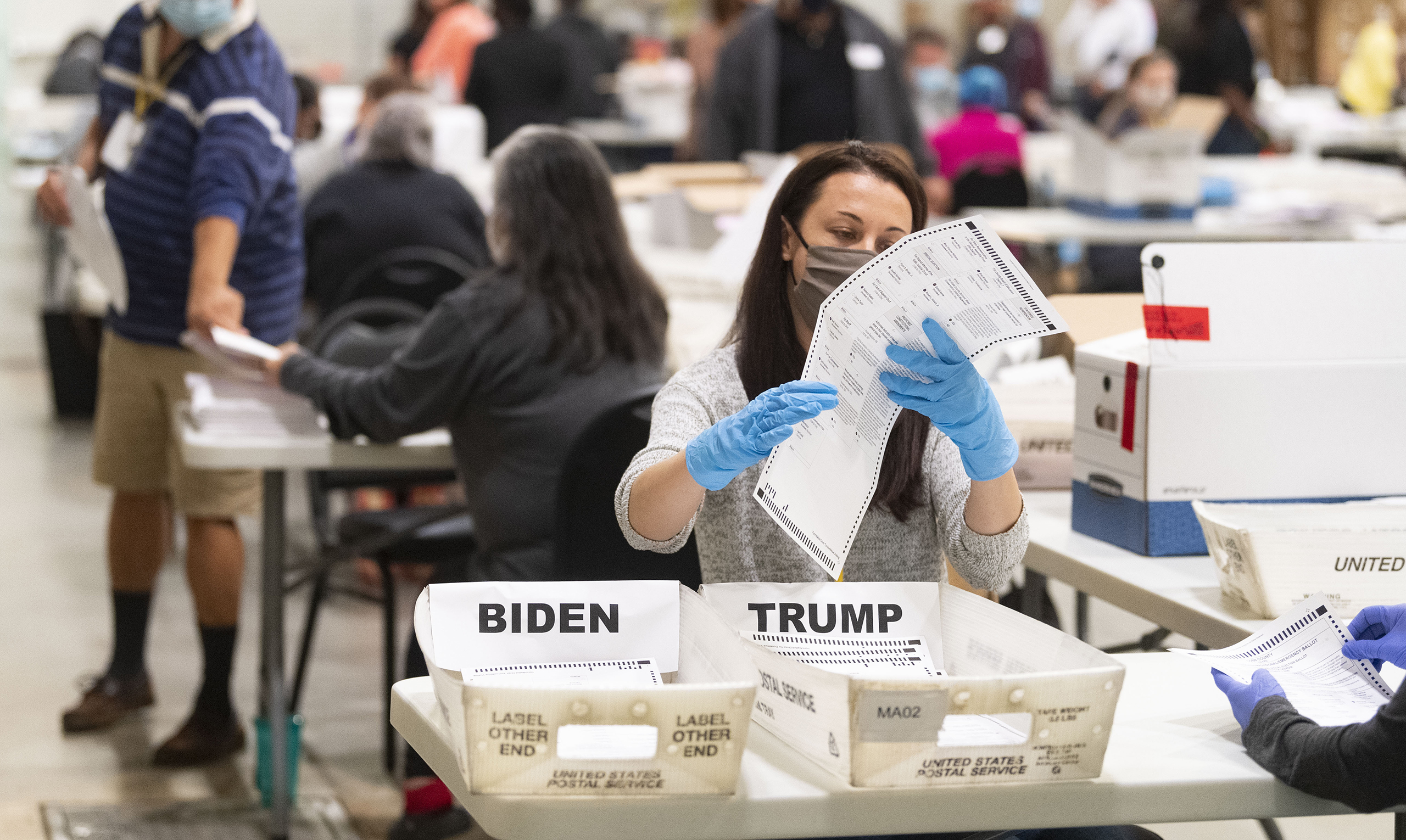

Effective election administration requires keeping up to date with a complex and dynamic set of policies and practices. A new local election official must be brought up to speed quickly, and as the chief official in charge of local elections, must gain a deep understanding of laws, statutes, and administrative procedures at the local, state, and federal levels.

Increasingly, local election officials also must be experts in many fields: human resources, information technology, direct mail processing, public relations, cybersecurity… the list goes on and on. And in 2020 there was a completely new skill to learn — how to conduct an election during a pandemic.

“We were one of the first counties to post election results on the internet. That took some doing… [then] I’m having to become a social media expert… Now, I’m a cybersecurity expert. Right now, I’m a public health expert, because I’m having to… figure out how to deploy all these protocols on how to conduct voting in person under a pandemic.”

– LOCAL ELECTION OFFICIAL

The challenge is heightened for some elections offices, where small or part-time staffs have few with whom to share in this journey or consult with on questions. In our 2020 Democracy Fund/Reed College Survey of Local Election Officials, over half of respondents said they work in an office with just one or two staff members who may not even be full-time. Some work alone with only volunteer and/or temporary support, and with varying levels of expertise and support available from other local departments or from the state.

These realities underscore the importance of initial and ongoing education, as well as a connection to other professionals doing this work — all key ways local officials prepare to do their jobs effectively and respond to a continually changing elections landscape.

Job Training for Local Election Officials

The good news is that, overall, local election officials do report receiving initial and ongoing training — and they believe this training is effective. The officials we surveyed are relatively satisfied with the current level of job training that they receive, which is not insubstantial. Nationwide, about 85 percent of them received initial training when they first began their work, and almost 95 percent receive ongoing job training. Among local election officials receiving ongoing training, more than 90 percent go through the process at least once a year. Over 70 percent of local election officials believe that these trainings are either “extremely” or “very” effective, with ongoing training receiving higher ratings than initial training.

We also asked about training during in-depth interviews with local election officials. In these conversations, some officials said that initial training was overly general and not focused enough on the actual tasks that needed to be performed. Others shared that when they were first hired, a host of pressing needs took priority, in conflict with participation in training.

“But, of course, there wasn’t any time for training when I was sworn in on the early part of May and June. We’re having an election. So that is reality… you kind of had to learn by… as the saying goes… ‘Baptism by fire.’ We just kind of jumped in and just did it.”

– LOCAL ELECTION OFFICIAL

By comparison, ongoing training is often tied to state and national association meetings or statewide training sessions, allowing for local election officials to interact with each other and learn from shared experiences. We also heard in our in-depth interviews that formal and informal communications networks are vital avenues for learning and innovation. We suspect that linking ongoing training to venues that support collegiality and network-building not only enhances the effectiveness of the training, but also contributes to the positive evaluations local election officials give training.

“There’s a lot of training required for election officials and the state will host regional training sessions, and so we’ll end up seeing a lot of the familiar faces… there’s definitely a lot of interaction and sharing of ideas with how to do it the best way. And just the willingness to share that information and help the other clerks.”

– LOCAL ELECTION OFFICIAL

We also learned that local election officials from the largest jurisdictions were the least likely to receive initial or ongoing training. Those from large jurisdictions were least likely to find trainings effective compared to their counterparts in smaller jurisdictions.

There could be any number of reasons for this, but one possibility is that local election officials in larger jurisdictions are more likely to come from other staff positions and would have had on-the-job training. This may lead them to feel underserved by additional training — a sentiment expressed by at least one interview participant.

“[The training] was not geared to me as somebody who had worked in the business for 20 years, but if I didn’t know anything, I’m not sure I would have come away terribly well prepared.”

– LOCAL ELECTION OFFICIAL

Another explanation is that training programs are better suited to local election officials from the numerous small jurisdictions than the comparatively lower number of large jurisdictions. In our interviews, some local election officials from larger jurisdictions noted that training programs can have a “one size fits all” approach that they find less valuable. Many smaller jurisdictions include clerks who are being trained more broadly, rather than just on election administration, and such trainings might provide a greater utility in their day-to-day work as clerks. Election work as a percentage of the average local election official’s workload is highly variable and, in part, depends on the size of the jurisdiction. For jurisdictions with fewer than 25,000 registered voters, only 55 percent of local election officials report that elections constitute a majority or more of their workload. For jurisdictions with over 100,000 registered voters, 100 percent say elections constitute the majority of their workload.

“That group gets together at least three times a year. We get together for training. Again, some of it’s elections, but some of it’s the other stuff that we do such as budgeting, and some of us even have HR roles in our county, and some of them even have IT roles in our counties too…”

– LOCAL ELECTION OFFICIAL

Many local election officials go above and beyond requirements when enrolling in ongoing job training. While almost 70 percent of those who receive ongoing training said that their state mandates training of some sort, more than 40 percent voluntarily enroll in regular training, and almost 25 percent pursue certification beyond their state’s requirements.

While our survey did not explore the role local election officials play in developing training, our interviews did identify a number of these officials who have become trainers in their own work with state associations. These individuals shared a sense of pride and excitement about the role that more senior officials can play in helping colleagues across the state. We can imagine many ways that these trainers become an important part of the connective tissue for elections officials in a state, building community as they convey knowledge and expertise.

Cybersecurity Preparation in Elections Offices

While the last year added many new worries for local election officials, cybersecurity has long been a key concern in the elections community — and it continues to grow in importance. For some local election officials, addressing cybersecurity needs poses challenges to attracting and retaining the right talent.

“[I]t’s very difficult to attract the talent that you need in the election industry and it’s becoming more complex. It used to be a very simple process, but now with the technology and cybersecurity that keeps me up at least every other night, that stuff’s not going away.”

– LOCAL ELECTION OFFICIAL

We asked local election officials about a series of tasks they might be performing to increase cybersecurity for elections. In our 2018 survey, we asked election officials only if they had conducted these cybersecurity tasks, if they planned to, or if the tasks felt “not applicable to my situation.” That question produced high “not applicable” responses, and local election officials told us that some of these cybersecurity tasks were handled by other agencies at the local level or by the state. We included these options in our 2020 survey, the responses to which — as shown in the next figure — provide a far more accurate picture of what tasks are being completed, and at what level of government.

On the whole, local election officials stated that they had recently completed most cybersecurity tasks, or planned to do so in preparation for the November 2020 election. For eight of the nine tasks we asked about, over 45 percent of local election officials planned to complete them by the election.

Across the board, large jurisdictions are more likely to perform tasks associated with cybersecurity than smaller ones. On average, a local election official in a jurisdiction with over 250,000 registered voters planned to complete two more of the nine tasks than an official from a district serving fewer than 5,000 registered voters.

While some local jurisdictions show comparatively low rates for some tasks, it does not mean those tasks are not being completed. When we dig deeper into criminal background checks, for example, a quarter of respondents reported that “another local office” handles background checks, and 16 percent reported that their state office handles them, while 32 percent responded that this task wasn’t applicable to them. The only tasks where “not applicable to my situation” exceeds 10 percent are “criminal background checks” (32 percent), “disabling wireless peripheral access” (18 percent), and “held cybersecurity training sessions for employees or elections workers” (19 percent).

The smallest jurisdictions were the most likely to answer “not applicable” and the most likely to report that tasks are handled by another local office or by the state. Fifty-two percent of those serving over 250,000 registered voters had plans to conduct background checks in-house (which they had either already completed or planned to complete before the election). But only 23 percent of jurisdictions with under 5,000 voters had similar plans. These small jurisdictions were much more likely than the largest jurisdictions to say that background checks were handled at the state level (21 percent vs. 7 percent) or that such checks weren’t applicable in their situation (32 percent vs. 20 percent).

The survey offers insight and focus for efforts to improve cybersecurity practices. For example, over a quarter of respondents said that, in their case, multi-factor authentication and a cybersecurity communication plan were handled by the state elections office, not at the local level. Over 20 percent of respondents said that background checks, wireless access methods such as Bluetooth, and computer system audits are handled by other local offices.

When approaching reforms to increase multi-factor authentication, therefore, efforts should be directed at state election departments. Improvements in other areas of security might be best targeted at local governments as a whole rather than at election offices specifically.

Support Networks for Local Election Officials

With so many small offices, it’s not surprising that local election officials reach out to other organizations or individuals for professional or personal support. No office is an island — even for the nine cybersecurity tasks we asked about, three-quarters of local election officials reported that one or more of these tasks was handled by another local office or the state election office (including over half of jurisdictions with more than 250,000 registered voters).

Our survey demonstrates the importance of these support networks. Over 90 percent of local election officials agreed that they had received sufficient guidance from state and federal authorities regarding the security of their election systems. This rate of agreement held up regardless of size, but smaller jurisdictions were much more likely to “strongly” agree, whereas larger jurisdictions often only “somewhat” agreed with this statement.

Almost half of all respondents said they belonged to their state association of local election officials, and over a quarter reported belonging to a regional or local association of election officials, but only about a quarter of officials in the smallest jurisdictions reported joining these organizations.

Across the board, in fact, local election officials in smaller jurisdictions were less likely to belong to the organizations that we asked about. This difference is particularly noticeable on questions about membership in national and international organizations such as the Election Center and the International Association of Government Officials (iGO).

One caveat is that our survey may not be capturing all of the organizations that local election officials belong to. For example, clerks may participate in associations particular to their other township or municipal duties. While not specifically elections-focused, these associations may provide a connection to others facing similar elections challenges in their states.

“If it wasn’t for those national organizations and opportunities to network with others across the country, you wouldn’t have anybody to talk to. Because there’s nobody in the county organization that has a clue what we do over here.”

– LOCAL ELECTION OFFICIAL

In the COVID-19 environment, local election officials had to rapidly implement changes in order to administer safe and accessible elections. We asked respondents which organizations were helpful in providing resources and information they could use to do their work amid the pandemic. Local and election-related resources were most likely to be consulted: Over half of local election officials said they used information from their state election office, state association of election officials, and their state or local health authority. About 35 percent reported using information from the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in their planning, and under 20 percent reported using any of the other sources we asked about, which were mostly national-level election organizations.

Larger-jurisdiction local election officials were slightly more likely to use each of these sources during the pandemic than officials in smaller jurisdictions. Those serving under 5,000 voters reported using between two and three sources on average (out of the nine we asked about, including “other resource”), while local election officials in the largest jurisdictions reported using between four and five sources on average.

Wide Participation and General Satisfaction — With Key Areas for Improvement

Local election official training and connection to others in the profession are important to ensuring that elections are fair, efficient, and secure. Our survey findings indicate that while there are areas for improvement in the initial training local election officials receive, and possibly a need to tailor trainings to better fit the realities of larger jurisdictions, training is generally meeting the local election community’s needs.

Professional associations and other organizations provide critical connections between officials that often find themselves performing unique duties within their governmental organization. While we find participation in these organizations to be high among the larger jurisdictions, there is room for improvement in helping smaller jurisdictions connect with regional, state, and national organizations and resources.

Finally, training and professional associations contribute to the formal and informal networks among officials, which are avenues for sharing expertise, responding to challenges, or simply swapping war stories with friends and colleagues. More research needs to be done to understand the value these informal connections add, and how they may be further fostered and supported in the elections community.