Seven years ago, two of the three authors of this report began a research study to understand American support for democracy and the potential appeal of authoritarian alternatives. Since then, we have surveyed thousands of Americans using multiple survey instruments. Over the course of this project, we have gone beyond an initial battery of questions and pursued multiple avenues to understand and explain what people really believe and why. To do so, we:

Our most recent survey in November 2022 offers us the chance to explore the most important uncertainty emerging from our earlier research. Namely, to what extent were responses to our previous questions an artifact of the Trump presidency? Are Republicans really more supportive of authoritarian actions than Democrats? Or, are Democrats just as willing to support abuses of power in a polarized environment when they control the executive branch?

Following the 2020 election, we can understand how views shifted when control of the White House changed hands — even if we haven’t yet emerged from an era in which Donald Trump is at the center of our politics. The results show that support for foundational principles of liberal democracy are discouragingly soft and inconsistent.

The consistent theme across our analysis is that while American support for the abstract principles of democracy is very high, it is considerably shallower under specific scenarios and conditions. In our 2017 VOTER Survey, we found that nearly 90 percent of Americans believed having a democracy is a good thing. However, support for the idea of democracy was higher than support for its keystone components, such as checks and balances, comfort with pluralism, acceptance of unpopular election results, and condemnation of real-world instances of political violence. Many Americans disregard these principles when their side’s agenda is slowed by political opposition, their leaders say that they know best, or their preferred candidate claims a rigged election.

Our 2017 VOTER Survey included the alarming result that only 54 percent of Americans consistently provided the pro-democracy answer across a battery of these questions:

Now, looking across multiple years of data — during a period that spans a Republican and a Democratic presidential administration — we find that support for democracy is more fragile than we thought and that it is particularly susceptible to partisan interests. We look at how consistent Americans are in their responses to the previous questions about strong leaders, army rule, democratic political systems, and preference for democracy. We also analyze responses to an expanded battery of questions that tests support for checks and balances, a military takeover to reduce corruption, and political violence. We further consider whether Americans consistently accepted the results of the 2020 presidential election, starting with the November 2020 wave of the survey.

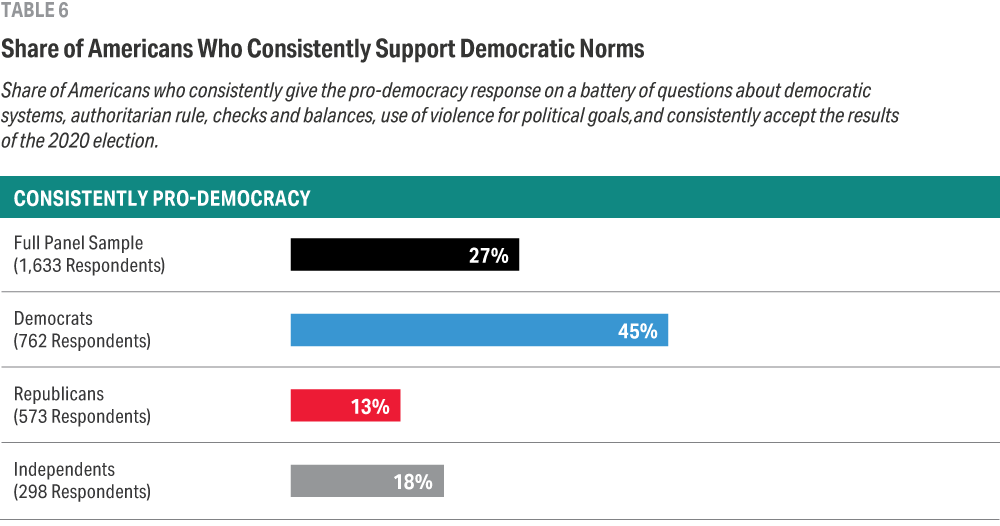

When we look across the surveys from 2017 to 2022, the share of Americans who consistently provide the pro-democracy response to this expanded battery of questions drops to 27 percent. This means that the majority of the same respondents expressed support for democracy and its main components at some point but also expressed at least one anti-democratic view across multiple survey waves and 30 questions.

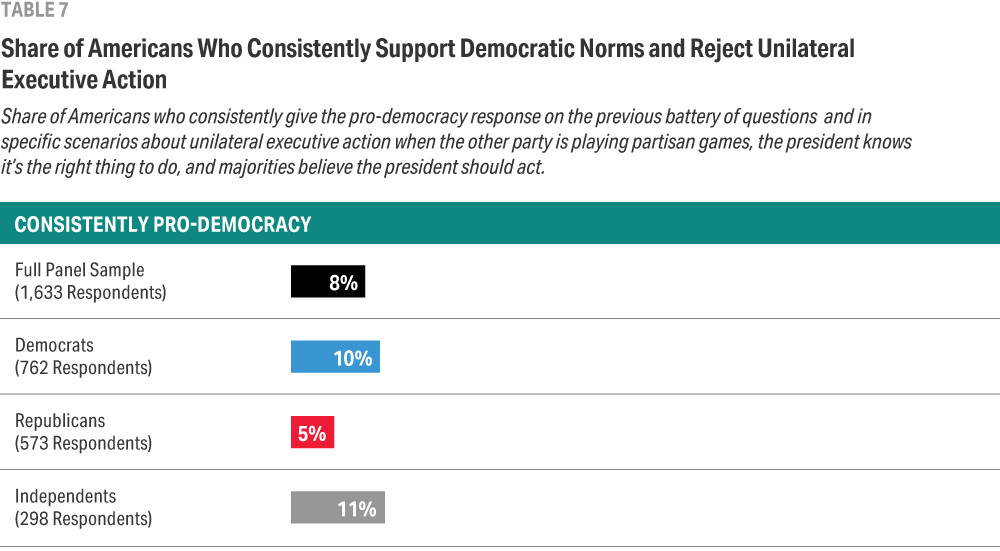

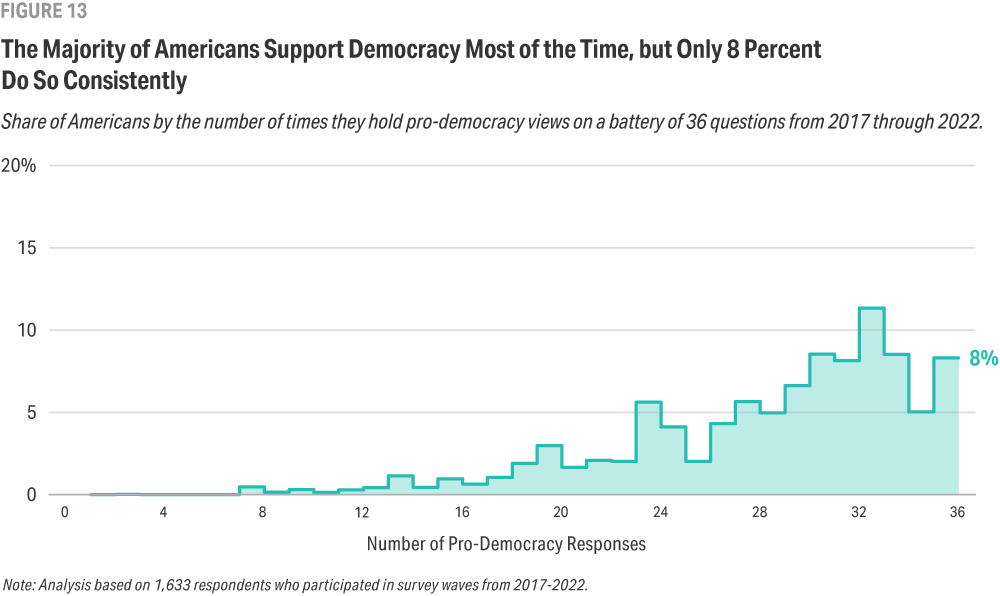

We also asked Americans how much they approved of a president acting unilaterally in specific scenarios. To test for the effects of partisanship, we varied whether respondents were told that a Democratic/Republican president is engaging in unilateral action or that President Trump (in the 2019 wave of the survey) or President Biden (in the 2022 wave of the survey) is doing so. When we include responses to these questions in our analysis of how consistent people are in their democratic views, only 8 percent of Americans consistently provide the pro-democratic response across all questions and all survey waves.

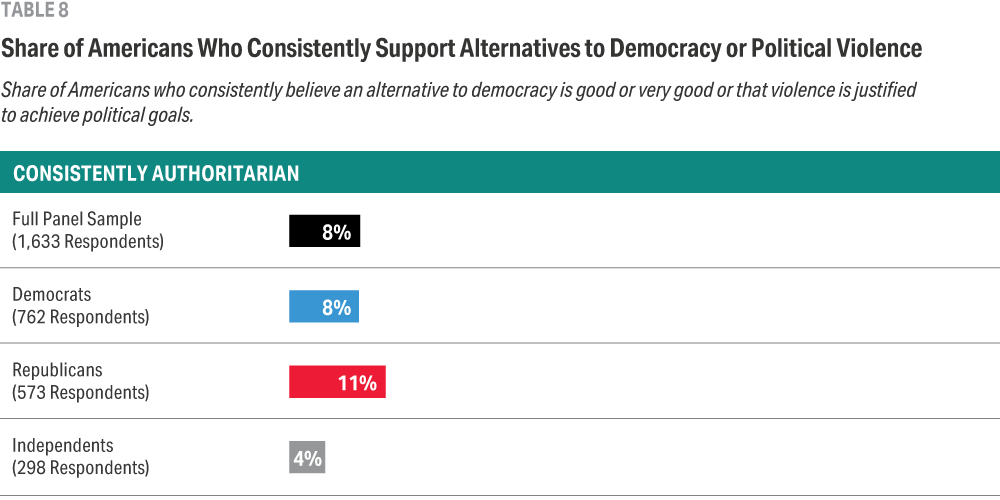

At the other end of the spectrum, we find relatively few staunch authoritarians in our surveys across the years. We define consistent authoritarians as anyone who consistently supports any of the alternatives to democracy — having strong leaders, army rule, or favoring a military coup to deal with corruption — or who consistently justifies violence to achieve political goals. About 8 percent of Americans overall met these criteria. We also find that consistent support for political violence and other types of uncivil political behavior, like harassing and intimidating people from the other party, is quite limited among Americans, with the majority of the population consistently rejecting this type of behavior. Though it is encouraging that consistent authoritarian views are not widespread — or at least openly embraced — among the American public, people expressing these views still represent a non-trivial share of the population, particularly in a country with a population of over 258 million adults. Moreover, given the share of Americans who equivocate in their commitment to democracy, we worry that there is a significant segment of the population that may be willing to embrace or accept the cause of authoritarian figures if and when it is in their partisan and political interests. Much like the political elites who are semi-loyal to democracy — as put by political scientist Juan Linz — and tolerate anti-democratic behavior by politicians from their own party, so can ordinary citizens who waver in their support of democracy empower the views of an authoritarian minority.i The real risk to American democracy, then, is the significant share of people who support or accept anti-democratic behavior and political violence when their side does it and who are willing to give up on democracy to advance their partisan interests. In this report, we interrogate this double standard with respect to democracy by exploring how the consistency of views about abstract democratic principles, alternatives to democracy, checks and balances, unilateral executive action, electoral norms, and political violence has changed between 2017 and 2022.

Growing Evidence of a Partisan Double Standard

Since we first began tracking public support for democracy, a growing body of scholarly literature has emerged to explain why citizens support anti-democratic leaders and actions, even as they express abstract support for democracy.

Whether we describe it as a “partisan double standard”ii or “democratic hypocrisy,”iii this is now a well-documented pattern across various contexts. It is most pronounced in countries with the highest levels of mass affective polarization and among the most affectively polarized individuals within a single country.ii,iv-xii When party leaders take anti-democratic actions — like changing electoral rules to their advantage, weakening the power of checks and balances, or subverting elections outright — their supporters are willing to follow along. While they do not openly condone anti-democratic behavior, they believe their side is justified in doing what they believe is necessary and right.

KEY FINDINGS FROM PAST REPORTS

As part of our larger inquiry into the nature of public support for democracy, Democracy Fund published several reports over the past six years as part of our Voter Study Group initiative (www.voterstudygroup.org). Our past findings include the following:

Follow the Leader: Exploring American Support for Democracy and Authoritarianism by Lee Drutman, Larry Diamond, Joe Goldman (March 2018)

- The overwhelming majority of Americans support democracy and most of those who express negative views about it are opposed to authoritarian alternatives.

- The highest levels of support for authoritarian leadership come from those who are disaffected, disengaged from politics, deeply distrustful of experts, culturally conservative, and have negative views toward racial minorities.

Testing the Limits: Examining Public Support for Checks on Presidential Power by Lee Drutman, Larry Diamond, Joe Goldman (June 2018)

- Large majorities of Americans believe that the president should be subject to oversight and constraints on executive power.

- Those who have a favorable view of President Trump are much more likely to express a preference for less accountability and oversight. Among Trump supporters, lower levels of education and news interest are associated with lower support for checks on executive authority.

Democracy Maybe: Attitudes on Authoritarianism in America by Lee Drutman, Joe Goldman, Larry Diamond (June 2020)

- American support for a “strong leader who doesn’t have to bother with Congress or elections” (24 percent) is below the levels found in the 1999, 2006, and 2011 World Values Surveys (29 percent, 32 percent, and 34 percent respectively) and matches the level last found in 1995. Support for “army rule” on the other hand matches the World Values Survey’s high point, found in 2011 (17 percent).

- Significant proportions of the public appear ready to challenge the legitimacy of the 2020 election under certain scenarios. About 57 percent of Democrats say it would be appropriate for a Democrat to call for a do-over election because of interference by a foreign government. Close to 29 percent of Republicans say it would be appropriate for President Trump to refuse to leave office based on claims of illegal voting in the 2020 election.

Other reports in this series from the Democracy Fund Voter Study Group include Jumping to Collusions: Americans React to Russia and the Mueller Investigation (2018), Behind the Curtain: Americans Prepare for the Mueller Report (2019), and Theft Perception: Examining the Views of Americans Who Believe the 2020 Election Was Stolen (2021).

Many go to extraordinary lengths to rationalize what their side does as appropriately democratic. As Suthan Krishnarajan concludes, “When violations of democracy are indisputably clear, many citizens find ways to not perceive undemocratic behavior as undemocratic if they agree with it politically. This might provide one explanation for why democratically elected leaders in today’s democracies are so often able to get away with violations of democracy without facing electoral backlash.”xiii

In many cases, partisans can justify their side’s behavior because they believe their political opponents are the true threats to the republic. This “subversion dilemma” can “result in a death spiral for democracy.”xiv However, partisans are most likely to believe these accusations under certain conditions. “Aspiring autocrats may instigate democratic backsliding by accusing their opponents of subverting democracy…” explains Alia Braley and colleagues. “Would-be authoritarians’ ability to weaponize the subversion dilemma may depend on a larger set of mutually reinforcing polarizations. These include increasing partisan identity strength, polarized views on policy, dislike of opposing partisans, dehumanization of opposing partisans, stereotypes of opposing partisans, and ethnic antagonism.”xiv

Our study is consistent with these findings and it adds to the growing discussion in two main ways. First, our study is unique in its use of panel data: we can observe the same individuals under two presidents from different parties (previous studies have manipulated the circumstances in experimental surveys). Second, we ask a battery of questions that allow us to go from the most abstract to the most specific, giving us a fuller picture of public attitudes toward democracy.

“The real risk to American democracy, then, is the significant share of people who support or accept anti-democratic behavior and political violence when their side does it and who are willing to give up on democracy to advance their partisan interests.”

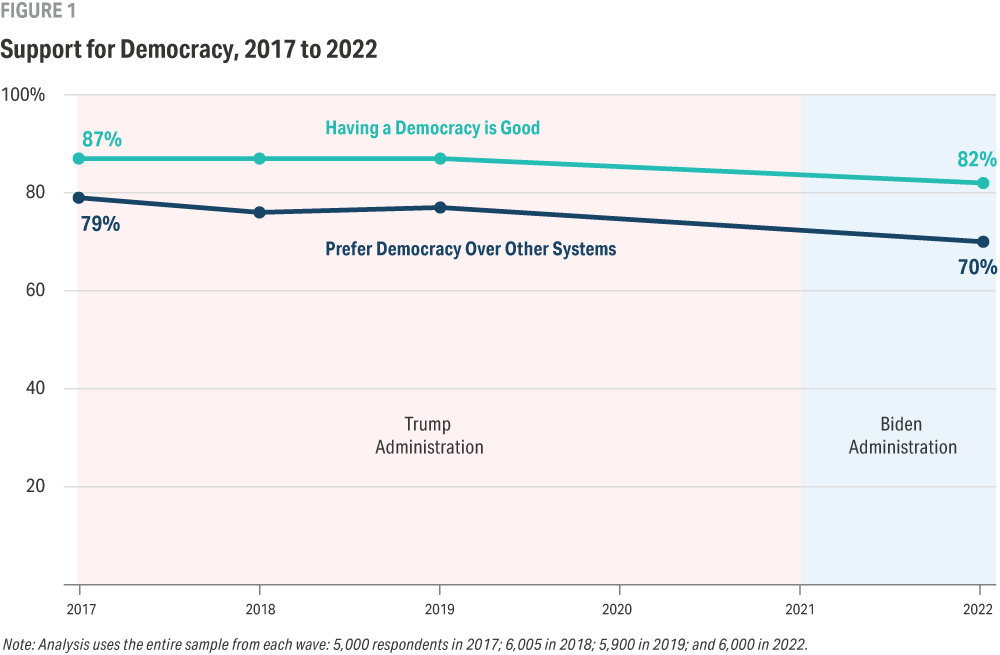

2. Strong Support for Democracy in the Abstract, Softer Support in the Specifics

Support for democracy in general — whether by agreeing that having a democracy is good or that democracy is preferable to other systems of government — has remained high over time, dropping slightly in November 2022. Using the entire sample in each survey wave, we find that more than eight in 10 Americans (87 percent) thought having a democracy was either good or very good from 2017 through 2019. This figure was 82 percent in November 2022. Similarly, we see that most Americans agreed that democracy is preferable to other systems, but this share declined between 2017 and 2022 (from 79 percent to 70 percent).

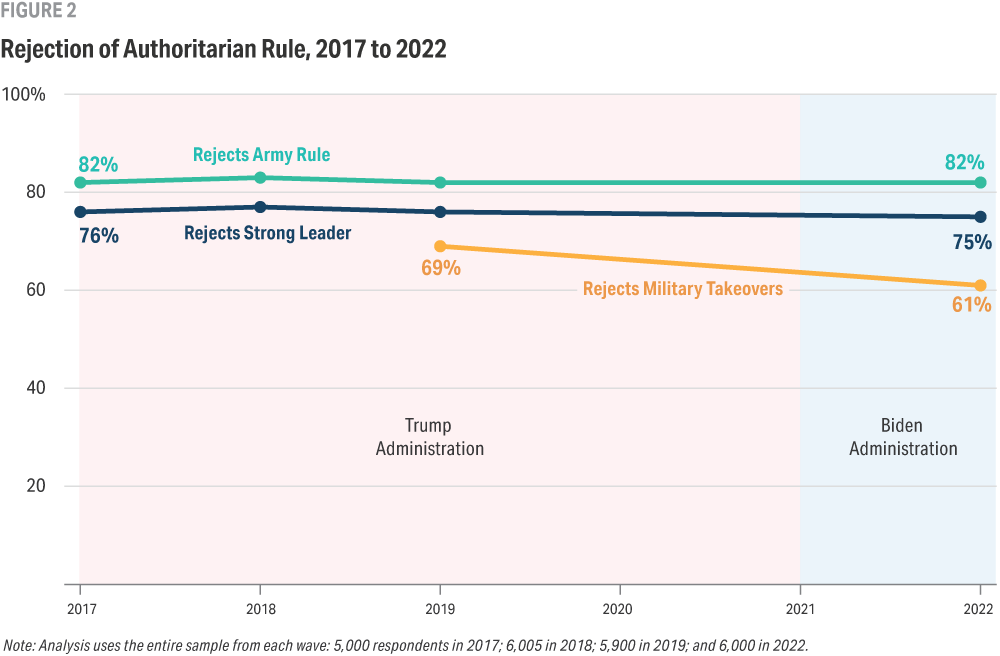

Overwhelming majorities oppose alternatives to democracy. More than eight in 10 Americans reject army rule every year that the question is asked, and about three-quarters reject having a strong leader who doesn’t have to bother with Congress and elections.

To ensure that people understood what army rule could entail, we elaborated on the question and asked if they favor or oppose the following scenario: “In some countries, military leaders have suspended elections, closed down the legislature, and temporarily taken charge of the government in order to address extreme corruption. What would be your view if the military took these steps in the United States?” The majority of Americans reject such a military takeover in both 2019 and 2022 (69 percent and 61 percent). This share is lower than the share of Americans who reject army rule or a strong leader, but this reflects the inclusion of a “Don’t Know” option in the question about a military takeover. Indeed, the share of people who are uncertain about their views toward a military takeover increased from 19 percent to 23 percent. Actual support for a military takeover is lower in 2019 and 2022 (13 percent and 15 percent) while the share of Americans who think army rule would be fairly or very good remained stable from 2019 to 2022 (18 percent in both years).

Support for democracy in the abstract may be high because there is a strong social desirability bias to say democracy is a good system. Moreover, people may have different definitions of democracy in their mind when answering questions about whether democracy is good or preferable to other systems. We further probed support for democracy by asking about support for concrete examples of checks and balances, which are a key dimension of liberal democracy. For each example, our questions asked respondents to express which of the two statements is closest to their views, even if neither statement is exactly right:

- Rule of law

- Since the president was elected to lead the country, he should not be bound by laws or court decisions that he thinks are wrong, or

- The president must always obey the laws and the courts, even if he thinks they are wrong

- Media scrutiny

- The news media should scrutinize the president and other politicians to ensure they are accountable to the American people, or

- The news media should allow the president and politicians to make decisions without being constantly monitored.

- Congressional oversight

- Members of Congress should provide oversight of the president and executive branch, even if the President is in the same party, or

- Members of Congress should give the president freedom to make the decisions he feels are right for the country.

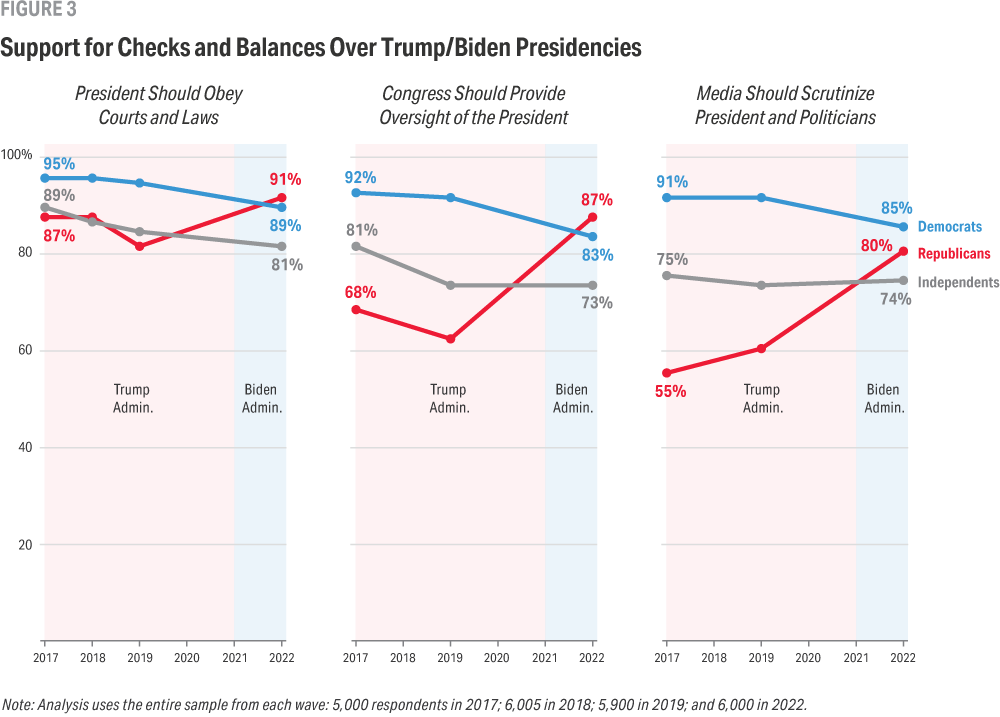

The trends over time from 2017 to 2022, illustrated in Figure 3, show that majorities of Americans supported the pro-democracy statements related to checks and balances. These trends also reveal that for partisans — and particularly for Republicans — support for checks and balances varies depending on which party is in the White House.

Throughout the years when Trump was in office, Republicans were the least supportive of congressional oversight and media scrutiny of politicians. By 2022, when Biden was in office, support for congressional oversight increased significantly from 2019 (from 62 percent to 87 percent). Support for media scrutiny also experienced a large shift from the Trump administration in 2019 to the Biden administration in 2022 (60 percent to 80 percent). Among Democrats, support for congressional oversight dropped from 2019 to 2022 (91 percent to 83 percent) as did support for media scrutiny (91 percent to 85 percent), but these changes among Democrats are considerably smaller compared to Republicans.

“These trends also reveal that for partisans — and particularly for Republicans — support for checks and balances varies depending on which party is in the White House.”

Across party lines, majorities of Americans agree that the president should obey the laws even if he thinks they are wrong. From 2017 through 2022, support for this democratic norm remained high and stable, though there were still traces of a partisan double standard. Republican support for the president obeying laws and courts increased from the Trump to the Biden administration (81 percent in 2019 to 91 percent in 2022), whereas among Democrats it decreased by half as much (94 percent in 2019 to 89 percent in 2022).

Independents were generally stable in their support for these forms of checks and balances. Their level of support for media scrutiny remained almost unchanged from 2019 to 2022 (73 percent to 74 percent). Meanwhile, support for congressional oversight among independents remained flat at 73 percent from 2019 to 2022, but the share of independents who expressed support for having the president obey the law dropped slightly between these two years (84 percent to 81 percent).

3. Wavering Support Over Time and a Partisan Double Standard

In the previous section, we explored topline trends over time in support for democracy, rejection of authoritarianism, and support of checks and balances. But these averages across the years may hide important changes in the opinion of the same individuals, particularly if they exhibit a partisan double standard, changing their views toward democracy depending on whether their party is in or out of power. In the exploration that follows, we focus only on those respondents who participated in all the survey waves to see whether their view towards democracy remain consistent over time or not.

When looking at these respondents, we find evidence that many people do waver in their support of democracy, only championing it when their party is out of the presidency. We also identify a segment of the population — a minority, to be sure, but too large to be dismissed as a tiny fringe — that consistently embraces anti-democratic attitudes.

As in the previous section, we focus on seven questions that capture different dimensions of democracy. These questions were asked in the 2017, 2019, and 2022 waves of the survey and fit into the three broad categories of support for democratic systems, support for alternatives to democracy, and support for checks and balances.

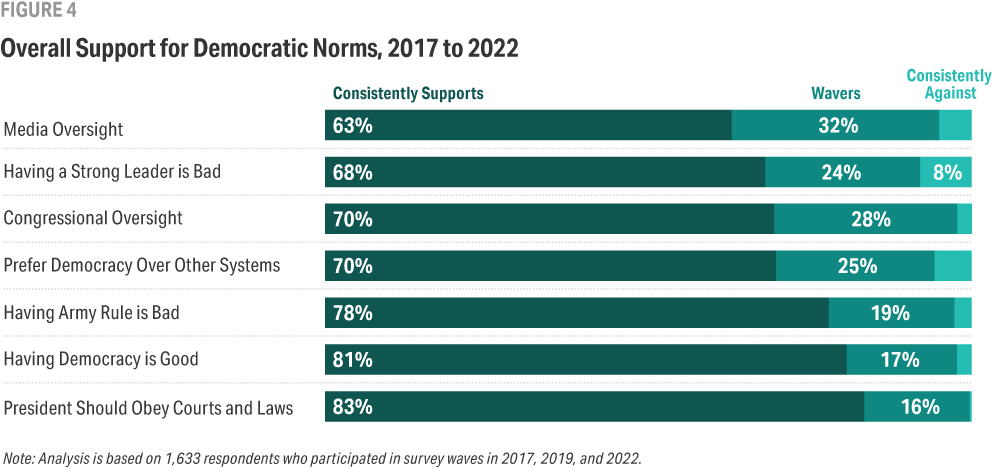

From 2017 through 2022, a majority of Americans were consistently supportive of various aspects of democracy, although there is a wide range of difference in support depending on the question examined. At one end, about eight in 10 Americans (83 percent) consistently supported having the president obey courts and laws — these are those who, even with a change from a Republican to a Democratic administration, maintained their belief that the president should be beholden to the law. At the lower end, only about 63 percent of Americans were consistent in their support of having the media scrutinize the president and politicians.

Encouragingly, Americans consistently providing authoritarian responses to these questions were a tiny fraction of the population. For example, very few Americans consistently said a strong leader who doesn’t have to deal with Congress and elections is a good thing (8 percent) or that they preferred a non-democratic system of government (6 percent).

While genuine authoritarian views are relatively rare, what’s more common — and potentially more perilous in an extremely polarized two-party system — is fluctuating support for key aspects of liberal democracy. Depending on the question, between 16 percent and 32 percent of Americans changed their views toward one of these democratic norms across the three survey waves. Americans wavered the most on their responses to the question of whether the media should scrutinize the president and politicians (32 percent wavered) and whether Congress should provide oversight (28 percent wavered). As we show later, most of this fluctuation is consistent with a partisan double standard — supporting democratic accountability only when the opposing party is in office.

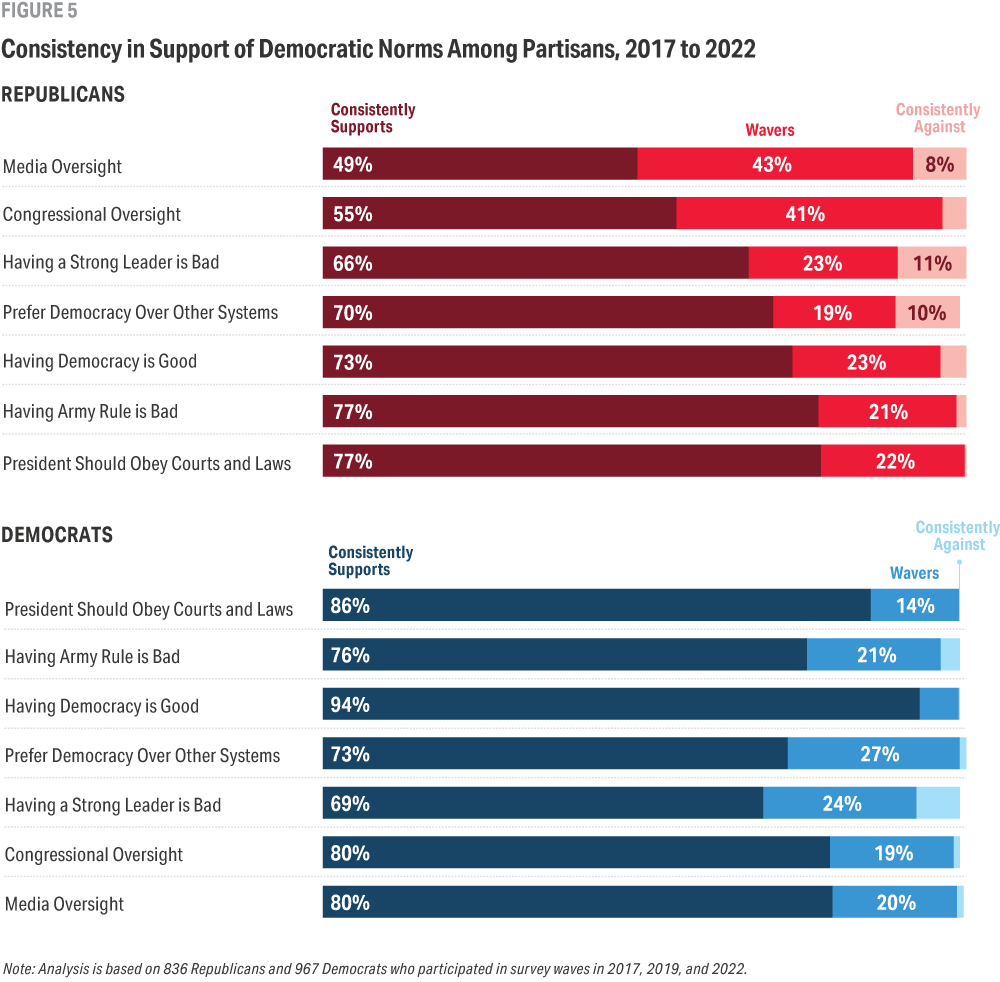

Among Republicans, only about half (49 percent) believed consistently across administrations that the media should scrutinize the president and other politicians to ensure they are accountable to the American people. Significant portions of Republicans changed their minds about whether members of Congress should conduct oversight of the president and executive branch when the president is in their preferred party (41 percent) and about having a strong leader who doesn’t have to bother with Congress or elections (23 percent).

Democrats were more consistent in their support of democratic norms during this period but were not immune from wavering views on democracy. About a quarter of Democrats changed their views about whether having a strong leader would be good (24 percent) and about their preferences toward democracy over other systems (27 percent). Relatively few Democrats changed their views about whether democracy is a good political system (6 percent) or wavered in their support of having the president obey laws and courts (14 percent).

“While genuine authoritarian views are relatively rare, what’s more common — and potentially more perilous in an extremely polarized two-party system — is fluctuating support for key aspects of liberal democracy.”

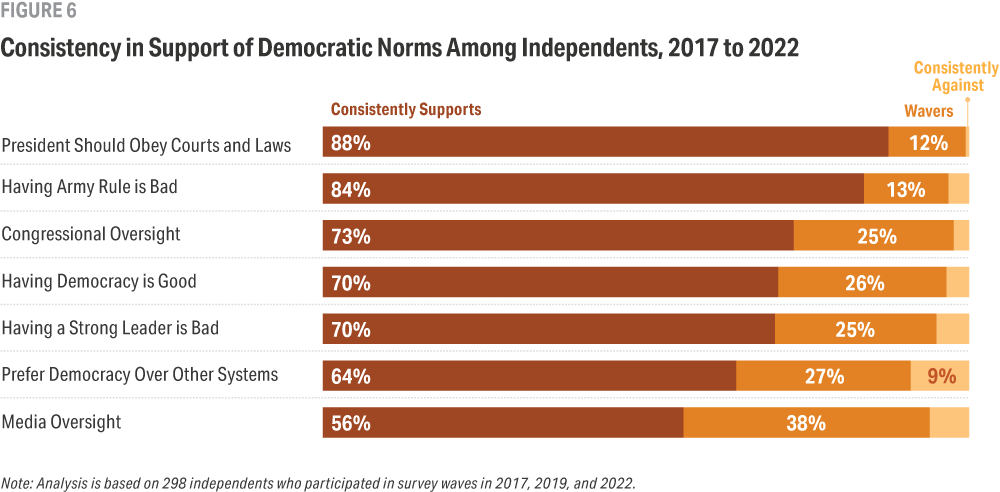

Independents also wavered considerably in their support for democratic norms. Only for the norm of the president obeying laws and courts and rejecting army rule did fewer than a quarter of independents waver in their responses. But over a third of independents wavered on other democratic norms: 38 percent changed their minds regarding media scrutiny, 27 percent changed their views about preferring democracy to other systems, and 25 percent wavered in their views of having a strong leader who doesn’t have to deal with Congress or elections. These changes differ considerably from the stable trends we document in Section 2, underscoring the importance of looking beyond averages over time and focusing on how the same respondents change their views from survey to survey.

Wavering support for democracy among independents is likely due to reasons other than partisan interests, like anti-establishment sentiment, disaffection with the status quo, a contrarian stance, or views that are not well-defined. Other work has suggested that independents are more likely to punish anti-democratic behavior at the ballot box as they are less attached to parties.((In survey experiments, people are more likely to support democratic norm erosion when informed that their party wins control of most government branches, an effect that is more pronounced among those who perceive greater threat from the opposition party and who exhibit high levels of expressive partisanship.iii Other work using candidate choice experiments finds that most Americans care mostly about their party winning or obtaining their preferred policies than about democratic principles, with only about 13 percent of respondents in the study willing to vote against a candidate of their party who violates a democratic principle if it means voting against their own party.ii Comparisons of different surveys fielded in 2012, during the Obama administration, and in 2019, during the Trump administration, show that Democrats who exhibit high degrees of affective polarization were more likely to oppose constitutional protections under Obama while Republicans with high degrees of affective polarization were more likely to oppose these protections under Trump.vi Similar patterns are observed throughout several Latin American countries where survey respondents who voted for the incumbent president are more likely to support power grabs than those who voted for a candidate that lost.xv))

However, inconsistent views toward democracy among a significant share of independents indicates that this group may be vulnerable to certain types of anti-democratic sentiment. This is discouraging news for those who view independent voters as bulwarks of democracy.

Independents change their minds, but these changes don’t follow a detectable pattern or logic. Partisans, on the other hand, change their views much more predictably. They are willing to accept democratic norm violations only from their side. One explanation for their changing views toward democracy is simple partisan loyalty, a phenomenon that has been observed by several studies of the American public and abroad.((In survey experiments, people are more likely to support democratic norm erosion when informed that their party wins control of most government branches, an effect that is more pronounced among those who perceive greater threat from the opposition party and who exhibit high levels of expressive partisanship.iii Other work using candidate choice experiments finds that most Americans care mostly about their party winning or obtaining their preferred policies than about democratic principles, with only about 13 percent of respondents in the study willing to vote against a candidate of their party who violates a democratic principle if it means voting against their own party.ii Comparisons of different surveys fielded in 2012, during the Obama administration, and in 2019, during the Trump administration, show that Democrats who exhibit high degrees of affective polarization were more likely to oppose constitutional protections under Obama while Republicans with high degrees of affective polarization were more likely to oppose these protections under Trump.vi Similar patterns are observed throughout several Latin American countries where survey respondents who voted for the incumbent president are more likely to support power grabs than those who voted for a candidate that lost.xv)) We contribute to this body of work by analyzing panel data from a period when American democracy has been threatened and when questions about the health of American democracy have been salient in national conversations. With our panel data, we can observe the views of the same individual at different points in time and see if they change from one administration to the other in a way consistent with democratic hypocrisy.

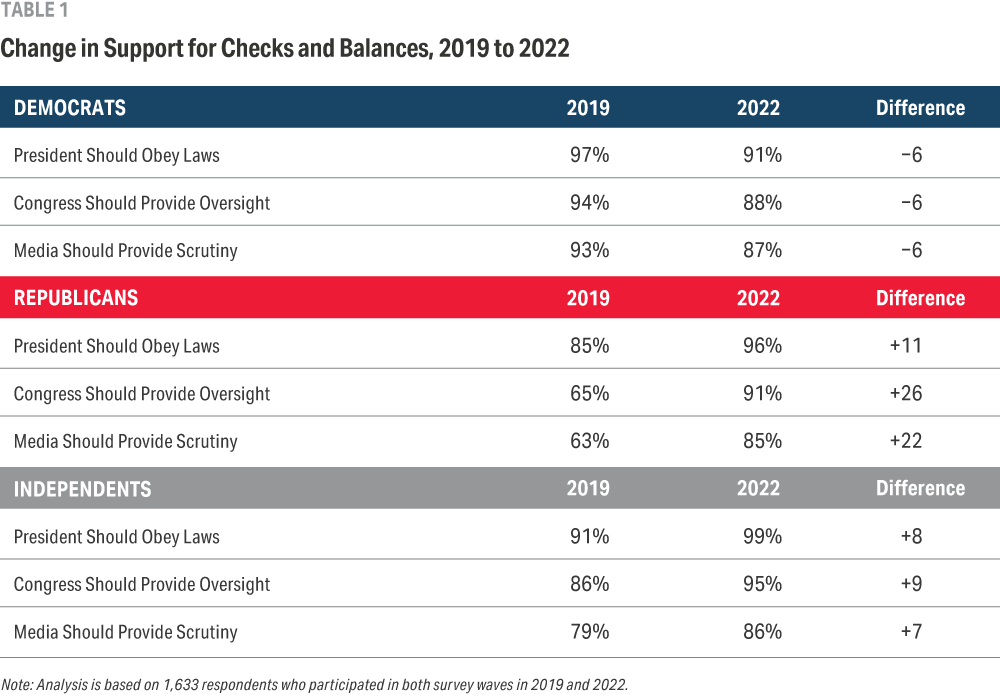

Table 1 shows how the same respondents change their views on checks and balances on the executive from 2019 to 2022. For all these questions, Republicans are the most flexible in their views, wavering in their support and opposition to democratic norms by far greater margins than Democrats and independents. Republican support for congressional oversight of the executive branch shifted most from the Trump to the Biden administration (65 percent to 91 percent). In contrast, support for congressional oversight among Democrats dropped by much less from 2019 to 2022 (from 94 percent to 88 percent). Whether these shifts in opinion are due to changes in the partisan composition of Congress or to the party of the president, they reveal a fragile commitment to a basic democratic norm of checks on the executive that should ideally remain constant regardless of partisan control of these institutions.

We see similar patterns regarding views on having the media scrutinize the president and other politicians and having the president obey laws and courts. Support for media scrutiny changed the most among Republicans from 2019 to 2022 (63 percent to 85 percent) compared to the change among Democrats (93 percent to 87 percent). Among Republicans, support for having the president obey laws and courts increased from 2019 to 2022 (85 percent to 96 percent), while among Democrats it decreased by about half as much between these two survey waves (97 percent to 91 percent). Among independent voters, support for all these democratic norms increased from 2019 to 2022, with their views toward congressional oversight being the largest shift (86 percent to 95 percent), followed by their views of having the president obey the laws and courts (91 percent to 99 percent), and finally by their views on media scrutiny (79 percent to 86 percent).

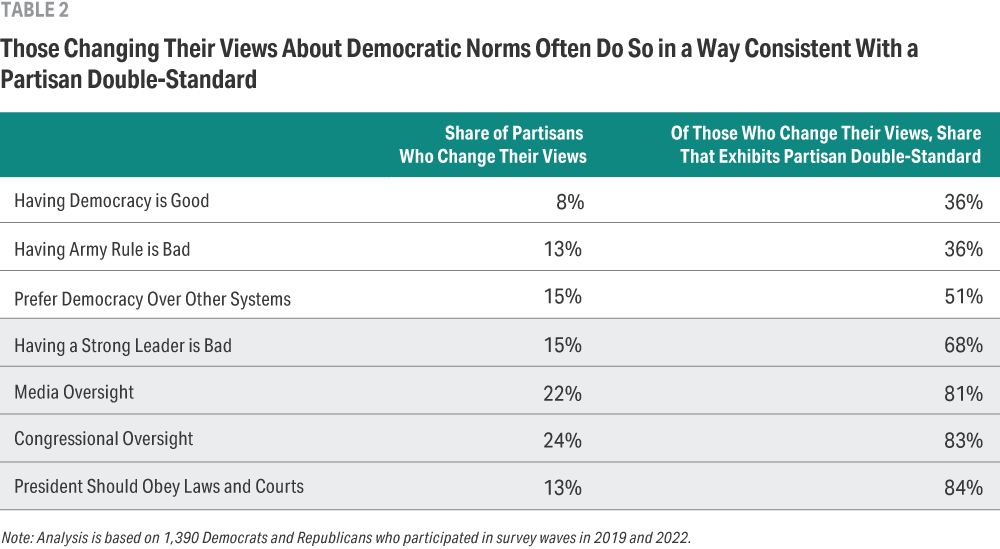

For most of the democratic norms we analyze, these shifts in views from 2019 to 2022 fit with a pattern of democratic hypocrisy. Focusing only on the Democrats and Republicans in the data, we find that for four of the seven norms, the majority of Americans changed their views in a way consistent with a partisan double standard, as shown in Table 2. Specifically, we find a partisan double standard on the four democratic norms that involve some check on executive authority — as opposed to those norms that were more related to general support for democracy or opposition to army rule.

“About 24 percent of Americans changed their views about congressional oversight from 2019 to 2022. Of these, 83 percent are Republicans who opposed the norm in 2019 but supported it in 2022 or Democrats who supported the norm in 2019 but opposed it in 2022.”

For example, about 24 percent of Americans changed their views about congressional oversight from 2019 to 2022. Of these, 83 percent are Republicans who opposed the norm in 2019 but supported it in 2022 or Democrats who supported the norm in 2019 but opposed it in 2022. In other words, only 17 percent of those who changed their point of view did so in a way that did not favor their partisan interests.

Similarly, about 13 percent of Americans changed their views about having the president obey laws and courts. Of these, 84 percent are Republicans who opposed this norm in 2019 but supported it in 2022 or Democrats who supported it in 2019 but opposed it in 2022. The majority of Americans who changed their views about media oversight and having a strong leader also do so in a way that also suggests a partisan double standard.

Notably, when it comes to norms that do not involve some form of checks and balances on executive power, the portion of those who change their points of view are not as heavily driven by a partisan double standard. This is the case for opposing army rule, preferring democracy over other systems, and agreeing that having a democracy is good. For these norms, fewer than half of Americans who changed their views are doing so in a way consistent with a partisan double standard. In these cases, the majority of respondents are changing their answers to the survey for other reasons. These may include inattentiveness, not having a well-formed opinion on the topic, or providing insincere responses for contrarian or provocative reasons.

4. Specific Scenarios of Unilateral Executive Action

In the real world, few aspiring autocrats ask for public support to violate democratic norms. Instead, they offer compelling justifications for emergency authority. Autocratic leaders around the world have exploited public health emergencies, natural disasters, crime waves, and corruption, among other circumstances, to rule by decree or amass greater power, often with the approval of the public.

Reflecting this, we asked how appropriate it would be for the president to act without congressional approval under different real-world scenarios when the Constitution does not give them the explicit power to act. To test for a partisan double standard, we presented participants with one of two different prompts. One prompt read:

“Please read the following scenarios. How appropriate would it be for a Democratic or Republican president to take action on their own, even if the Constitution does not give them the explicit power to act without congressional approval.”

The other prompt asked directly about President Trump in 2019 or about President Biden in 2022:

“Please read the following scenarios. How appropriate would it be for [President Trump/Biden] to take action on their own, even if the Constitution does not give them the explicit power to act without congressional approval.”

The scenarios that they then respond to are:

- The country is facing an immediate military threat

- A large majority of the American people believe that the president should act

- The president knows it is the right thing to do for the American people

- The president has sought a compromise with Congress but the other party is playing partisan games

Though the scenarios vary, all questions explicitly present a tradeoff between respect for checks on executive authority and ignoring this democratic value. By directly stating that the actions of the president are being done even when the Constitution does not grant them the explicit permission to act without congressional approval, the question should leave little room for ambiguity about the nature of the behavior.

“Autocratic leaders around the world have exploited public health emergencies, natural disasters, crime waves, and corruption, among other circumstances, to rule by decree or amass greater power, often with the approval of the public.”

We recognize that, in reality, there is much debate about the constitutionality and democratic nature of some of these actions — a swift military operation by the president in response to a military threat, for example, is not necessarily unconstitutional. But we worry about unilateral action by the president because, around the world, democracies have been dismantled little by little through executive aggrandizement, often legally, and by presidents amassing more power than what the law explicitly allows.xvi, xvii The extent to which Americans are willing to give the president latitude without congressional oversight — and how their willingness is influenced by partisanship — can pose a grave, if subtle, danger to democracy. Moreover, we are also interested in how approval for the same type of unilateral action can change due to partisanship.

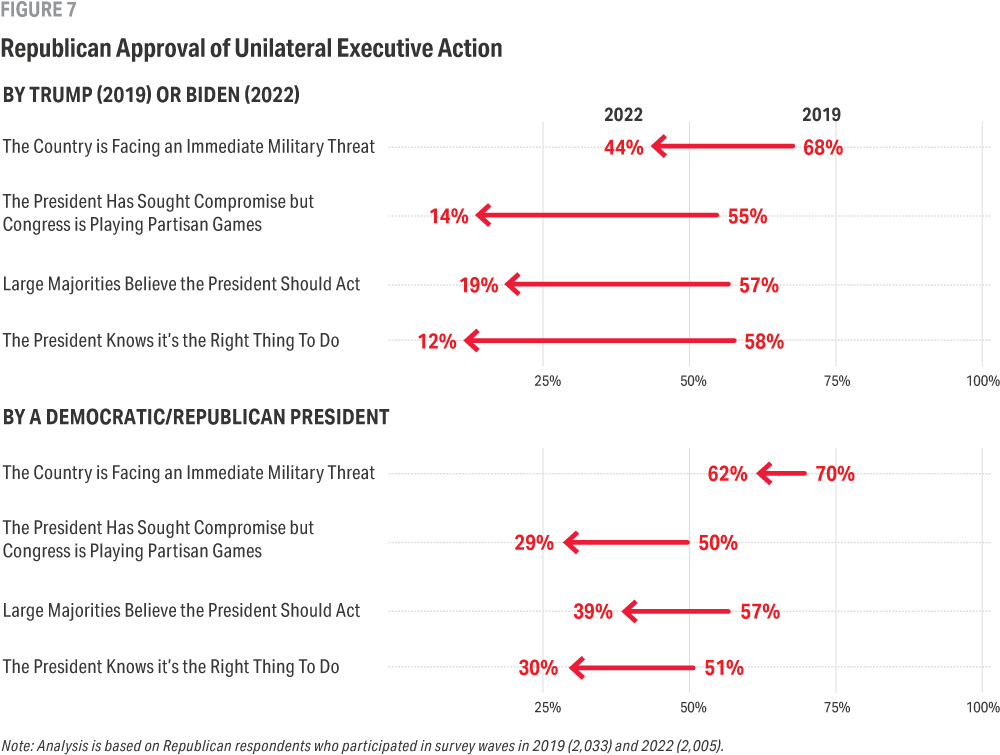

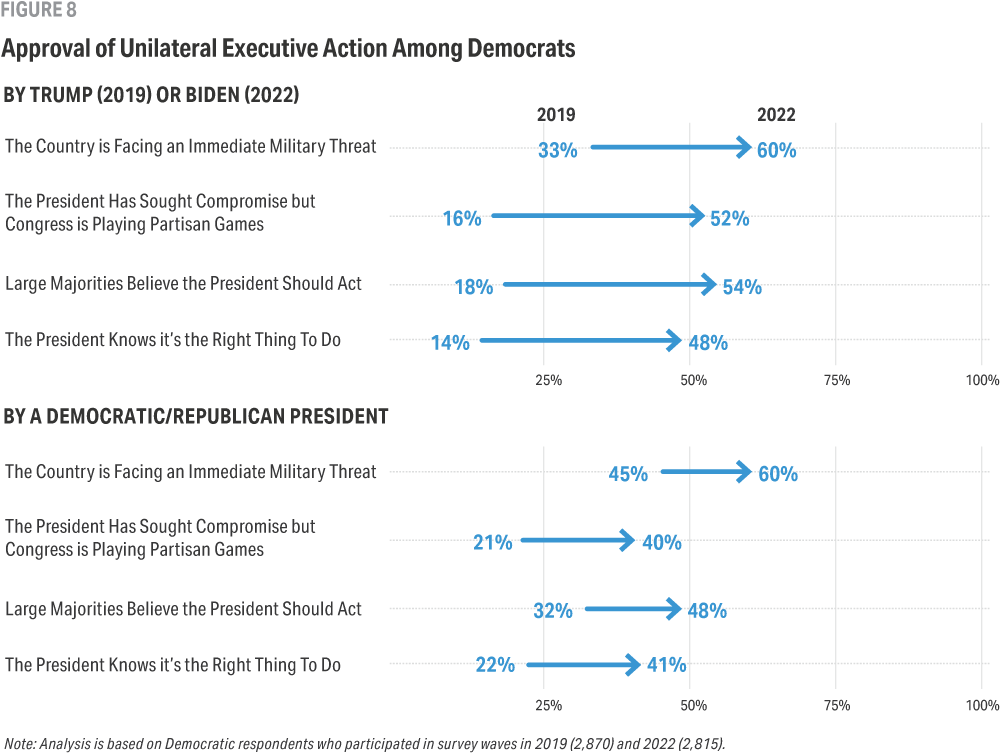

In our 2019 report we found that Republicans were more likely to agree that executive unilateral action is appropriate or very appropriate than Democrats. In response to all the scenarios, the majority of Republicans thought executive unilateral action is appropriate or very appropriate. By 2022, however, partisans reversed their views with President Biden in office (and a different partisan composition of Congress), as illustrated in Figure 7. Only the scenario of an immediate military threat drew majority Republican support for the appropriateness of unilateral action. In 2022, for instance, 30 percent of Republicans approved of unilateral executive action when the Democratic or Republican president provided the justification that they know it is the right thing to do, compared to 51 percent in 2019, and only 12 percent approved of it when they were told it was President Biden, compared to 58 percent when told it was President Trump.

Among Democrats, we see the same pattern but in reverse. In 2019, when Trump was president, the majority of Democrats disapproved of unilateral action. However, by 2022, Democrats were more supportive of unilateral action and this change was more pronounced when President Biden was mentioned.

Views toward unilateral action shifted among exactly the same group of people. Here we focus on respondents who are in the same experimental group in both waves of the survey. In the case of Democrats, when asked about executive action in the face of a military threat, the proportions essentially reverse themselves from 2019 to 2022. In 2019, only 24 percent said it would be appropriate for President Trump to initiate unilateral action; in 2022, 67 percent of them said it would be appropriate if President Biden did it. About 70 percent of Republicans said unilateral action in the face of a military threat would be appropriate under President Trump, but 47 percent said it would be appropriate if President Biden did it — still almost a majority of Republicans. Therefore, this scenario of a military threat against the country, when swift executive action is most needed even in a liberal democracy, can be seen as a baseline against which to compare the magnitude of the changes that occur in the other scenarios.

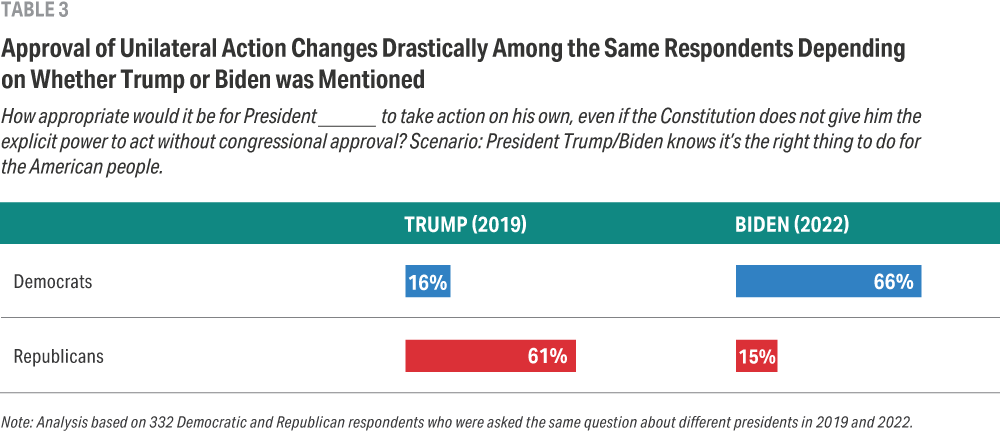

In the other scenarios, very few Republicans thought unilateral action was appropriate when President Biden was mentioned, even though most of them had said it was appropriate under President Trump back in 2019. For instance, when told President Trump knows it is the right thing to do, about 61 percent of Republicans said unilateral action is appropriate, but in 2022, only 15 percent said it is appropriate for President Biden to engage in unilateral action when he knows it is the right thing to do.

“We find that there is a strong association between affective polarization and the willingness to tolerate democratic norm erosion.”

In contrast, about 16 percent of Democrats polled in 2019 said unilateral action is appropriate when President Trump believes it is the right thing to do. But in 2022, 66 percent said it is appropriate when told President Biden knows it is the right thing to do. We observe similar patterns for the rest of the scenarios, like when majorities of Americans support the president and when the president has sought compromise with Congress. The sample size here is admittedly limited — but the shifts are so large that the result is clear.

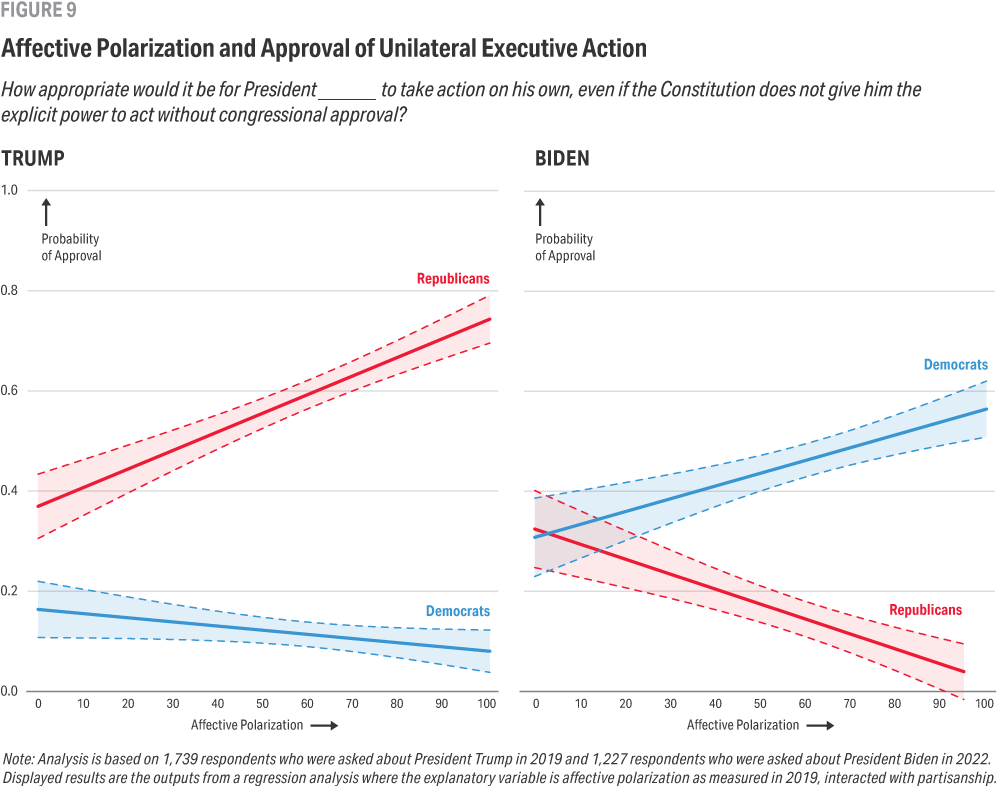

Like other research on polarization and democracy, we find that there is a strong association between affective polarization and the willingness to tolerate democratic norm erosion.iii, vi, xi, xviii Moreover, our analysis suggests that the partisan double standard — in this case approving of unilateral executive action when the president is a co-partisan and disapproving of it when the president is from the other party — is more pronounced among the most affectively polarized citizens.

We illustrate this with the scenario in which President Trump in 2019 or President Biden in 2022 initiate unilateral executive action without congressional approval because they know it is the right thing to do. As shown in Figure 9, in 2019, almost all Democrats rejected such behavior from President Trump. Republicans, in contrast, were more likely to approve of Trump engaging in unilateral action the higher their levels of affective polarization. In 2022, there is a dramatic reversal. Higher levels of affective polarization among Democrats are associated with higher levels of approval of unilateral action by President Biden when he “knows it is the right thing to do” while for Republicans, higher levels of polarization are associated with reductions in their level of approval of unilateral action by Biden. At the lowest levels of affective polarization, Democrats and Republicans have similar levels of approval of unilateral action by Biden.

“Higher levels of affective polarization among Democrats are associated with higher levels of approval of unilateral action by President Biden when he ‘knows it is the right thing to do’ while for Republicans, higher levels of polarization are associated with reductions in their level of approval of unilateral action by Biden.”

5. Respect for Election Outcomes

For democracy to remain sustainable, candidates, parties, and their supporters must accept losses. Healthy democracies need high levels of support for agreed-upon electoral norms, like conceding losses, upholding voting results, and peacefully stepping down from office.

There are worrying signs that confidence in the electoral system and popular respect for electoral norms are eroding in the United States. The combination of the country’s winner-take-all system with intensifying polarization have significantly increased the costs of losing an election, leading many citizens and politicians to openly question electoral results. It is in this context that we explore whether professed support for democracy among Americans translates to support for electoral norms or if partisanship compromises democratic views.

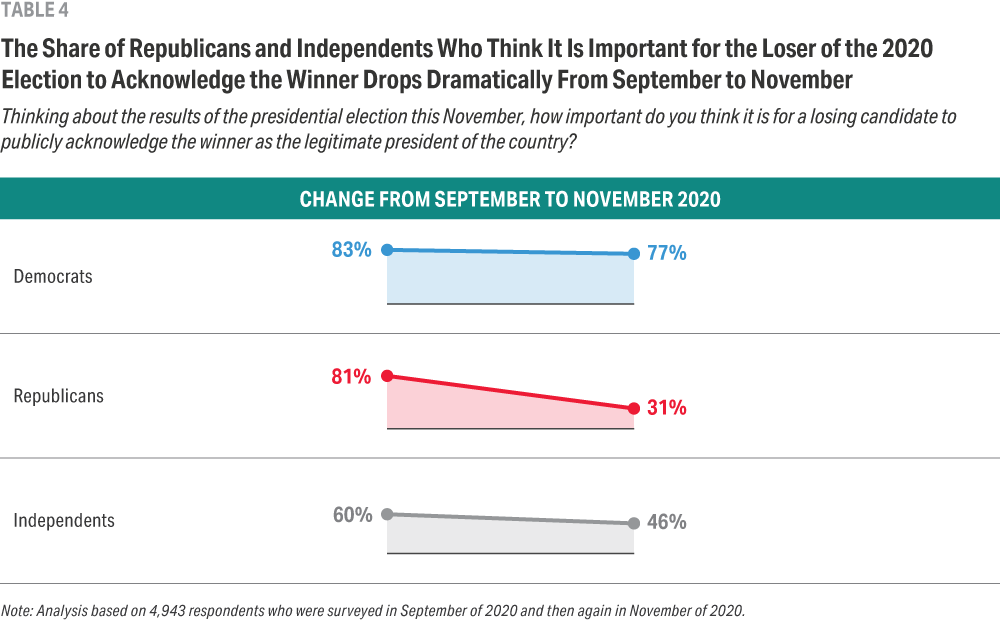

A particularly dramatic illustration is the plummeting support for the norm that the loser of a presidential election should publicly acknowledge the winner as the legitimate president. Table 4 shows that in September 2020, most Americans agreed that it is important for the loser of the election to publicly acknowledge the winner as the legitimate president of the country. Republicans and Democrats agreed that this norm is important at roughly the same level (81 percent and 83 percent), while 60 percent of independents shared this view.

Following the November 2020 election — and after the race had been called for Joe Biden — the share of Republicans who believed it is important for the loser of the election to publicly recognize the winner as the legitimate president dropped dramatically (from 81 percent to 31 percent). These are the same respondents from the September survey. Independents also declined dramatically in their support for this norm (from 60 percent to 46 percent), while the decline among Democrats was much more modest (83 percent to 77 percent).

“High dislike of the Democratic party and high approval of the Republican party makes it intolerable to have a Democrat as president and can make violations of American electoral norms more palatable.”

Among the 81 percent of Republicans who believed in September 2020 that it is important for the loser to acknowledge the winner of the election, 62 percent rejected Biden as the legitimate president after the election, 53 percent said it was appropriate for Trump to never concede the election, 87 percent thought it is appropriate for Trump to challenge the results of the election with lawsuits, and 43 percent approved of Republican legislators reassigning votes to Trump.

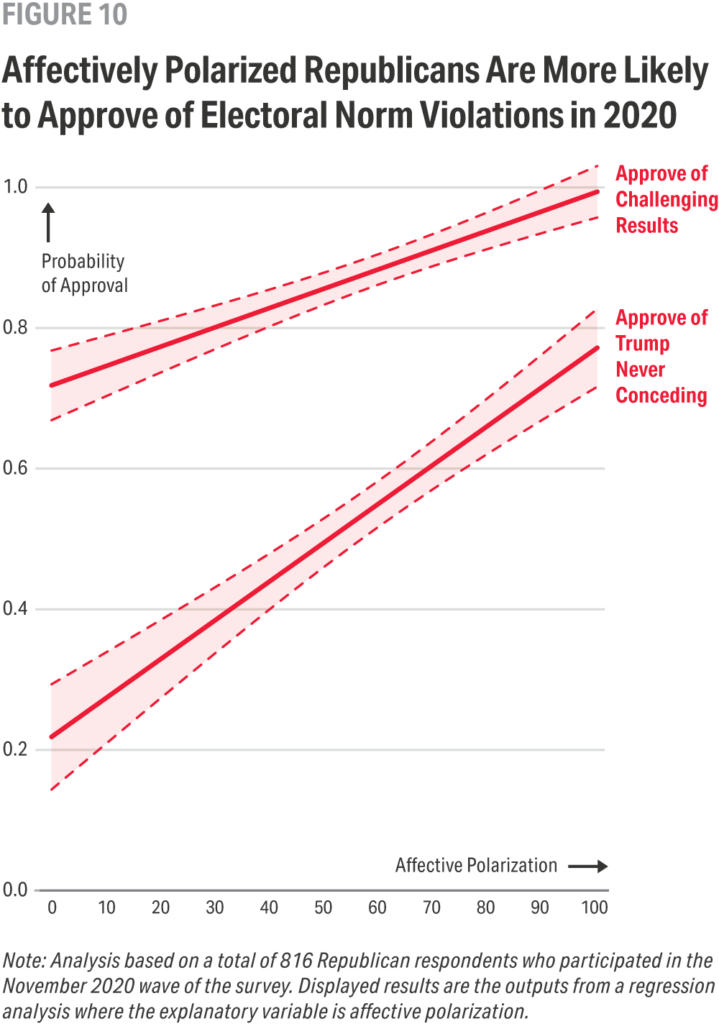

Republicans who exhibit higher levels of affective polarization were the most resistant to accepting an electoral loss. Figure 10 shows that increases in affective polarization — as measured in 2019 — among Republicans are associated with a lower likelihood of accepting Biden as the legitimate president after the race had been called for him. As affective polarization increases, Republicans become more likely to approve of Trump challenging the results of the 2020 elections with lawsuits, more likely to approve of Trump never conceding the race, and more likely to approve of Republican legislators reassigning votes to Trump.

Line graph shows that as affective polarization among Republicans increases, so does their approval of challenging election results and of Trump never conceding.

6. Justifying Political Violence

In democracies, ballots are the “paper stones” that prevent a society from resorting to violence as a way of resolving conflict and allocating power. But when the cost of losing an election is too high and the prospects of seeing an opposition party win office are difficult to digest, citizens may be tempted to use or condone violence to achieve their preferred outcome. They may become supportive of elites using violence to maintain or obtain power. When this happens, democracy breaks down: it is no longer the only game in town — violence is an option too.

Fears of political violence in the United States have been rising in recent years. Beyond the violent mob that tried to take over the U.S. Capitol on January 6, 2021 and revert the results of an election, there has been an increase in attacks against elected officials and election clerks, most of which have been committed by people on the far right.xix, xx For these reasons, it is worth exploring the extent to which support for political violence is widespread in the American public.

Studying political violence using survey data, however, presents important methodological challenges. First, self-reported survey responses can be misleading, particularly when it comes to contested issues.xxi Second, survey participants often rush through surveys and pick answers haphazardly, which may inflate support for violence when the question asks about how much violence is justified and there is only one option for “not at all” and no option for answering “don’t know.”xxii Moreover, questions about violence in general may be interpreted differently by different Americans, with some interpreting violence as something grave, like murder, and others interpreting it as harassment or insults. This makes responses difficult to compare.xxii Such issues likely mean that the questions we use could overestimate support for incidents of political violence.

Our surveys gauge support for political violence by asking the following questions:

- How much do you feel it is justified for people you agree with politically to use violence in advancing their political goals these days?

- When, if ever, is it OK for people you agree with politically to send threatening and intimidating messages to political leaders you don’t agree with?

- When, if ever, is it OK for an ordinary person you agree with politically to harass an ordinary person you don’t agree with politically on the internet in a way that makes the target feel unsafe?

“Only 2 percent of Democrats and 4 percent of Republicans consistently justified the use of political violence across the four survey waves.”

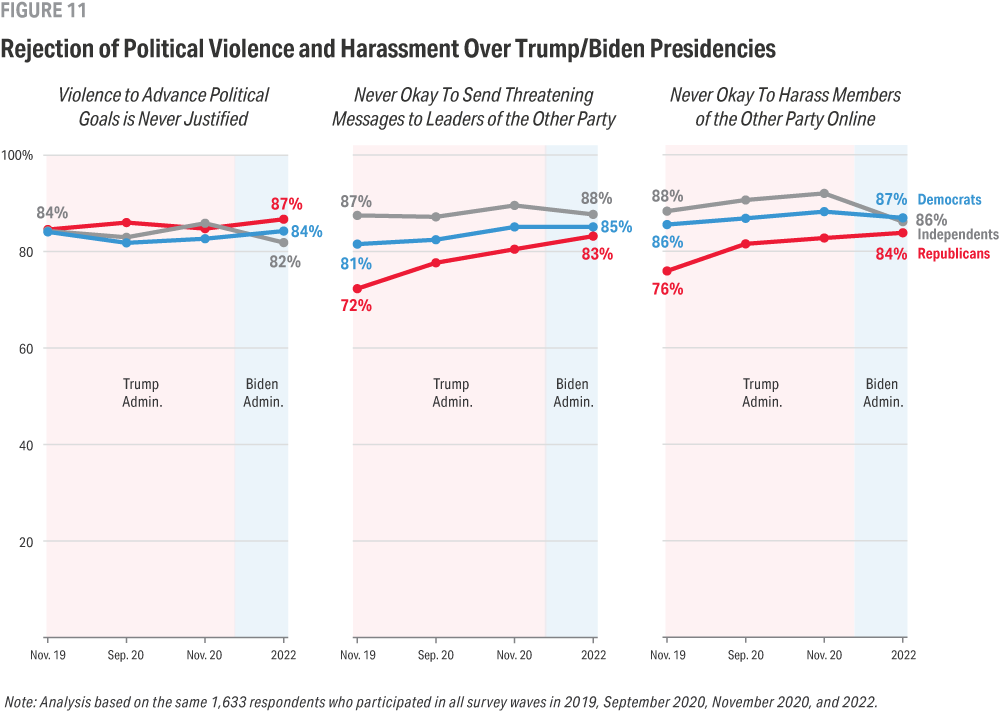

The American public is overwhelmingly opposed to political violence. Indeed, across survey waves, rejection of different types of violent and uncivil behavior remained high and stable from November 2019 through November 2022. A substantial majority of Americans, whether Democrats, Republicans, or independents, rejected sending threatening messages to leaders of the other party, harassing members of another party online, and using violence to advance political goals.

The most notable change we see is among Republicans. Their rejection of violence has increased from 2019 to 2022. While 72 percent of Republicans agreed that it is never okay to send threatening messages to leaders of the other party in 2019, this share increased to 83 percent by November 2022. Rejection of harassing members of the other party online also increased among Republicans from 76 percent in November 2019 to 84 percent in November 2022.

Attitudes toward political violence remained relatively stable across the years, with the majority of Americans rejecting violence. Among Democrats, rejection of political violence hovered around 84 percent during this time period. Among independents, rejection of political violence started off at 84 percent in 2019 and dropped slightly to 82 percent by November 2022. Among Republicans, rejection of political violence remained at around 86 percent from 2019 to November 2022.

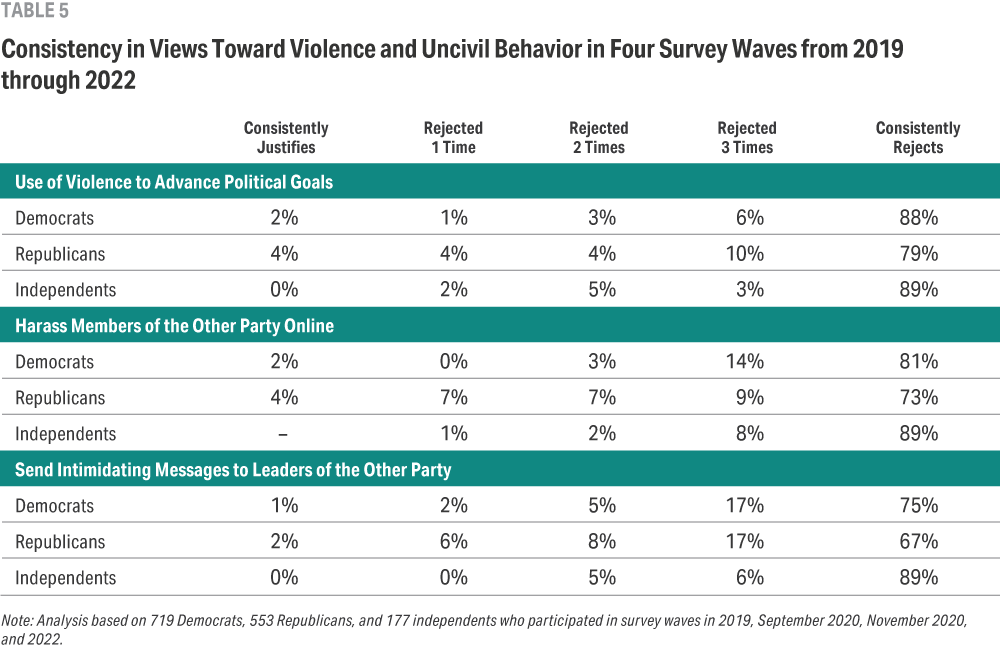

Given the methodological concerns highlighted before, a better way to gauge for genuine support for violence is to see if survey participants remain consistent in their views over time. When we look at the same respondents over time, we find that only a small share of the population consistently expresses support for violence and uncivil behavior across the years. Indeed, only 2 percent of Democrats and 4 percent of Republicans consistently justified the use of political violence across the four survey waves. The remaining participants switched their answers from one survey wave to the other, which may be due to not having well-defined views on the issue, rushing through the survey, or selecting responses at random.

Similarly, only 2 percent of Democrats and 4 percent of Republicans consistently justified the harassment of members of the other party online and sending intimidating messages to leaders of the other party. On this last question of sending intimidating messages to leaders of the other party, views were noticeably less consistent over time, suggesting that people might not have had a well-defined idea of what intimidating messages might include and were more likely to change their views on this behavior over time.

While the share of Republicans who consistently justified violence was considerably low and comparable to that of Democrats, Republicans were more inconsistent in their responses to the questions of violence and uncivil behavior. Close to a third of them changed their views at least once over time. Whether this was due to less well-defined views or speeding through surveys, this higher level of inconsistency among Republicans is notable.

Responses to January 6

According to the States United Democracy Center’s poll on political violence, Americans appear to be more willing to support political violence in specific hypothetical scenarios, such as if the government banned elections or jailed people critical of the government.xxiii The violent events that unfolded on January 6, 2021, are a specific and real case where many Republican voters perceived a danger to the democratic process that at least some believe warranted political violence. These events are a useful case for analyzing whether rejection of violence in the abstract translates to rejection of actual political violence. In addition, analyzing views toward a specific event helps us overcome some of the methodological limitations identified previously. We find that — in contrast to the overwhelming rejection of political violence identified before — the violent events of January 6th were viewed favorably by Republicans, illustrating how support for democratic norms frays in the face of partisanship and when considering concrete situations.

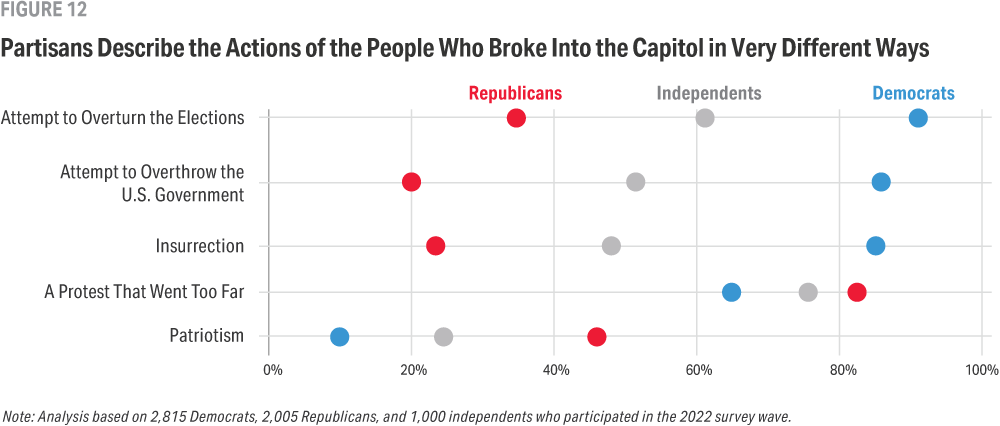

The January 6th events were perceived quite differently by Democrats and Republicans. Most Democrats described what happened as an attempt to overturn the elections, an attempt to overthrow the government, and as an insurrection. Only 35 percent of Republicans saw January 6th as an attempt to overturn the elections, 20 percent of them described it as an attempt to overthrow the government, and 23 percent described it as an insurrection.

Instead, 82 percent of Republicans and 76 percent of independents characterized January 6th as a protest that went too far and almost half of Republicans (46 percent) described these events as acts of patriotism. These different perceptions of the January 6th events fit with the idea that partisans are willing to break a norm — in this case the rejection of violence — when they perceive the other side to be engaging in anti-democratic behavior. By and large, Republicans believed their party’s rhetoric that the election was stolen by the Democrats — something very undemocratic — which made it acceptable for them to engage in violence to defend democracy, a patriotic act in their view.

The different understanding of the events color partisan approval of January 6th and subsequent investigations into them. While 89 percent of Democrats disapproved of what happened on January 6th, only 72 percent of Republicans and 64 percent of independents disapproved of it. Meanwhile, 14 percent of Democrats disapproved of the House Select Committee that was formed to investigate the January 6th events while 72 percent of Republicans and 39 percent of independents disapproved of it.

“In contrast to the overwhelming rejection of political violence identified before — the violent events of January 6th were viewed favorably by Republicans, illustrating how support for democratic norms frays in the face of partisanship and when considering concrete situations.”

7. Few Consistent Supporters of Democracy or Authoritarianism

There is no canonical measure to determine the number of Americans who are true authoritarians, democrats, or anything in between. Rather, we have asked various questions about our political system, asked similar questions in different ways, returned to the same respondents over time, and described real-life scenarios to dig deeper into individual beliefs.

In calculating an overall assessment, we test for:

- consistent belief that democracy is always a good system and better than its alternatives,

- consistent support for checks on executive authority as well as free and fair elections, and

- consistent rejection of authoritarian systems of government and the use of violence to achieve political goals.

Perhaps most importantly, support for democracy should come out ahead of support for party. Our definition of a consistent democracy champion is someone who accepts election results and checks on executive authority regardless of the partisan consequences.((While the VOTER Survey has occasionally asked questions that test support for pluralism (touching on, e.g., what characteristics make someone a “true” American), these were unfortunately not asked consistently enough to be included as a measure. However, we have little reason to believe that the addition of these questions would significantly change our findings based on the correlation of these views with the other measures we are tracking.)) Thus, we test whether support for basic democratic norms remains consistent across different presidential administrations and regardless of specific political leaders being named as the actors in a scenario (e.g., President Biden or Trump facing a check on their authority, acting unilaterally, or winning/losing an election).

When we look across responses to questions about preferred political systems, support for checks and balances, views about political violence, and acceptance of the 2020 election results, we find that only 27 percent of Americans were consistent democracy champions. In other words, across each wave of our survey, 27 percent of respondents always provided the pro-democracy answer. Broken down by partisanship, this group includes 45 percent of Democrats, 13 percent of Republicans, and 18 percent of independents.

The collective number declines considerably when we include scenarios about unilateral action by the president without constitutional authority or congressional approval. Specifically, we include the scenarios in which action is taken because the other party is “playing partisan games,” the president “knows it is the right thing to do,” and a large majority of the American people believe the president should act.

With these added conditions, 92 percent of Americans failed to meet the highest standard of consistent and unwavering support of democracy. Only 8 percent of Americans consistently provided the pro-democracy response across the battery of questions over time. This includes 10 percent of Democrats, 5 percent of Republicans, and 11 percent of independents.

At the other end of the democracy-support spectrum, we find a small percentage of Americans who are consistently authoritarian. Here we take a somewhat different approach. Rather than looking across our battery of questions, we focus on two core characteristics of authoritarianism.

- First, we look at the number of people who consistently believed over time that an authoritarian political system (featuring a strong leader or army rule) is favorable. For these questions we are looking to exclude survey respondents who accidentally or temporarily express support for an authoritarian system.

- Second, we look at the number of people who were consistent in their belief that violence is an acceptable way to achieve their political objectives. We consider those who consistently supported authoritarian political systems or who consistently justified political violence to be authoritarian.

In Section 2 of this report, we note that 78 percent of Americans have rejected army rule every year of our study and 68 percent consistently rejected having a strong leader who doesn’t have to bother with Congress or elections. But how many consistently endorsed an authoritarian system?

Across every survey wave, only 6 percent of Americans consistently supported any of the alternatives to a democratic system, with 5 percent of Americans unwavering in their support of a strong leader who does not have to bother with elections or Congress, and 2 percent supporting army rule. Likewise, 4 percent were in favor of a military takeover to reduce corruption both times this question was asked.

In Section 6, we find that most Americans consistently rejected violence to achieve their goals, but how many consistently endorsed it? Only about 3 percent consistently said that violence is justified to advance political goals. This number does not vary significantly by party affiliation.

Combining these figures to see the extent of consistent support for alternatives to democracy or for violence to achieve political goals, we find that 8 percent of Americans are consistently authoritarian — either repeatedly endorsing an authoritarian system or repeatedly endorsing political violence. Broken down by party, we see that a similar share of Democrats consistently endorsed an alternative to democracy or violence while a lower share of independents did so (4 percent). Support for a system other than democracy or political violence was highest among Republicans at 11 percent.

To be sure, these numbers are only our best guess, based on survey responses. It is possible that the share of authoritarians is higher. To the extent our results are biased because of differential non-response rates, we would expect higher non-responsive rates from authoritarians, who tend to be less engaged in politics and less inclined to respond to surveys. Though we have done our best to adjust for differential response rates, we must acknowledge this possibility.

Though 8 percent is small as a percentage, it represents approximately 21 million people in a country of more than 258 million adults. We also note that this “small” number is just about the same as the portion of Americans who are unwavering democracy champions, providing consistent pro-democracy responses across all the questions we analyze over all the survey waves.

The vast majority of Americans are neither consistently authoritarian nor consistently pro-democracy. To be sure, most Americans are closer to the consistent champions of democracy, equivocating on a couple of questions over time, as Figure 13 illustrates. Most of them say democracy is a good system; reject strong, unaccountable leaders and army rule; and tend to express support for checks on the executive while rejecting political violence. The catch for many seems to be when support for democracy comes in tension with their partisan interests and when partisanship is made salient to them.

8. Conclusion

Definitions of democracy can range from a minimalist view that emphasizes the peaceful transfer of power through free and fair elections to a thicker view that includes robust checks and balances.xxiv In our study we test this thicker definition, demanding a high standard of support for democracy that includes not just support for the abstract value of democracy and opposition to authoritarian rule, but also support for the separation of powers and the rule of law; rejection of political violence; and acceptance of electoral results, regardless of the partisan consequences and power.

The VOTER Survey, with its multiple waves spanning a Republican and Democratic administration, allows us to identify the consistent supporters of liberal democracy. As described in the introduction, we combine various questions from different years that capture the different dimensions of democracy for analysis. A consistent supporter of democracy, we assert, should express the pro-democratic view in all of these questions and at all times.

We are concerned that consistent support for abstract democratic principles is low, with only 27 percent of Americans consistently holding pro-democratic views on all questions of democratic systems, alternatives to democracy, checks and balances, acceptance of electoral results, and rejection of political violence. We are alarmed that only 8 percent of Americans hold a pro-democratic view on all the questions when we also include specific scenarios of unilateral executive action.

As we have shown, the share of true authoritarians in the country is quite limited. And we find that those who do not consistently and fully support pro-democracy norms are likely not doing so because they do not prefer democracy but rather because they have second thoughts when democracy is in the way of their partisan agenda. Paraphrasing Matthew Graham and Milan Svolik, who find that only between 4 percent to 12 percent of Americans would vote against a candidate of their own party who adopts undemocratic positions, Americans are often partisans first and democrats second.ii

“The simple conclusion is that many Americans believe that executive aggrandizement is okay when their side does it.”

The panel nature of our data makes clear that much support for anti-democratic backsliding and norm violation is motivated by partisanship. Citizens are far more consistent in their partisan orientations than they are in their support for various principles of liberal democracy, and they are even more inconsistent in their reactions to particular scenarios of executive aggrandizement. The simple conclusion is that many Americans believe that executive aggrandizement is okay when their side does it. This is not encouraging.

Perhaps this inconsistency reflects a limited understanding of the meaning of liberal democracy. Perhaps it represents a belief that un-democratic actions are justified (and pro-democratic) because the opposition party is a threat to democracy. Perhaps it represents inflated abstract support for democracy out of social desirability bias. Regardless of the explanations, our findings suggest that the reservoir of public commitment to preserve liberal democracy is distressingly shallow.

It seems that democratic backsliding may depend on the actions of political leaders. But political leaders can be limited by what the public lets them get away with. Unfortunately, our surveys show that they can get away with quite a bit. In contemporary American democracy, the citizenry does not provide much of a guardrail against democratic backsliding. Part of the reason for this is that high levels of polarization motivate Americans to believe that the other side is more extreme and anti-democratic than theirs, leading them to justify and rationalize anti-democratic behavior by their own side.

All of this is particularly worrisome at a time when core democratic norms and institutions are being challenged in unprecedented ways.

We began this study in 2017 out of a concern that American democracy might be far weaker than any of us would like to believe. We feared that our republic would see many challenges over the coming years that would test our political system and that public support would be critical for American democracy to make it through these challenges. Unfortunately, we were right about the challenges that were to come. We also were right to fear that large portions of the public would readily turn a blind eye to these transgressions.

Thankfully, all is not lost. The past seven years have seen countless examples of both leaders and citizens heroically championing our democracy. Election officials, judges, journalists, activists, and voters have defended democratic norms and stood up for our shaky institutions. As we enter yet another presidential election — this time with a former president and leading candidate going to trial for past attempts to subvert our democracy — it will be more important than ever that democracy’s champions are prepared.

References

i. Juan J. Linz and Alfred Stepan, “The Breakdown of Democratic Regimes: Crisis, Breakdown and Reequilibration. An Introduction,” Johns Hopkins University Press, 1978, p. 160.

ii. Matthew H. Graham and Milan w. Svolik, “Democracy in America? Partisanship, Polarization, and the Robustness of Support for Democracy in the United States,” American Political Science Review, Vol. 114, No. 2, May 2020, pp. 392–409.

iii. Gabor Simonovits, Jennifer McCoy, and Levente Littvay, “Democratic Hypocrisy and Out-Group Threat: Explaining Citizen Support for Democratic Erosion,” The Journal of Politics, Vol. 84, No. 3, 2022, pp. 1806–11.

iv. John Carey, Katherine Clayton, Gretchen Helmke, Brendan Nyhan, Mitchell Sanders, and Susan Stokes, “Who will defend democracy? Evaluating tradeoffs in candidate support among partisan donors and voters,” Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties, July 7, 2020, pp. 1–16.

v. Steven V. Miller and Nicolas T. Davis, “The Effect of White Social Prejudice on Support for American Democracy, Journal of Race, Ethnicity, and Politics, 2020, pp. 1–18.

vi. John Kingzette, James N. Druckman, Samara Klar, Yanna Krupnikov, Matthew Levendusky, and John Barry Ryan, “How Affective Polarization Undermines Support for Democratic Norms,” Public Opinion Quarterly, Vol. 85, No. 2, October 21, 2021, pp. 663–77.

vii. Elizabeth Gidengil, Dietlind Stolle, and Oliver Bergeron-Boutin, “The partisan nature of support for democratic backsliding: A comparative perspective,” European Journal of Political Research, Vol. 61, No. 4, 2022, pp. 901–29.

viii. Caterina Chiopris, Monika Nalepa, and Georg Vanberg, “A wolf in sheep’s clothing: Citizen uncertainty and democratic backsliding,” Working paper, 2021.

ix. Zhaotian Luo and Adam Przeworski, “Democracy and Its Vulnerabilities: Dynamics of Democratic Backsliding,” Available at SSRN 3469373, 2021.

x. Michael K. Miller, “A Republic, If You Can Keep It: Breakdown and Erosion in Modern Democracies,” The Journal of Politics, Vol. 83, No. 1, 2021, pp. 198–213.

xi. Jennifer McCoy, Tahmina Rahman, and Murat Somer, “Polarization and the Global Crisis of Democracy: Common Patterns, Dynamics, and Pernicious Consequences for Democratic Polities,” American Behavioral Scientist, Vol. 62, No. 1, 2018, pp. 16–42.

xii. Yunus Emre Orhan, “The relationship between affective polarization and democratic backsliding: comparative evidence,” Democratization, Vol. 29, No. 4, 2022, pp. 714–35.

xiii. Suthan Krishnarajan, “Rationalizing Democracy: The Perceptual Bias and (Un)Democratic Behavior,” American Political Science Review, Vol. 117, No. 2, May 2023, pp. 474–96.

xiv. Alia Braley, Gabriel S. Lenz, Dhaval Adjodah, Hossien Rahnama, and Alex Pentland, “Why voters who value democracy participate in democratic backsliding,” Nature Human Behaviour, 2023, pp. 1–12.

xv. Michael Albertus and Guy Grossman, “The Americas: When Do Voters Support Power Grabs?,” Journal of Democracy, Vol. 32, No. 2, 2021, pp. 116–31.

xvi. Nancy Bermeo, “On Democratic Backsliding,” Journal of Democracy, Vol. 27, No. 1, 2016, pp. 5–19.

xvii. Will Freeman, “Sidestepping the Constitution: Executive Aggrandizement in Latin America and East Central Europe,” Constitutional Studies, Vol. 6, 2020, p. 35.

xviii. Aytuğ Şaşmaz, Alper H. Yagci, and Daniel Ziblatt, “How Voters Respond to Presidential Assaults on Checks and Balances: Evidence from a Survey Experiment in Turkey,” Comparative Political Studies, Vol. 55, No. 11, September 1, 2022, pp. 1947–80.

xix. Rachel Kleinfeld, “How Political Violence Went Mainstream on the Right,” Politico, November 7, 2022, accessed October 25, 2023. Available at: https://www.politico.com/news/magazine/2022/11/07/political-violence-mainstream-right-wing-00065297.

xx. Rachel Kleinfeld, “The Rise of Political Violence in the United States,” Journal of Democracy, Vol. 32, No. 4, 2021, pp. 160–76.

xxi. Shanto Iyengar, “Impending Civil Strife or Further Evidence of Non-Attitudes? A Review Article,” Political Science Quarterly, Vol. 138, No. 2, June 7, 2023, pp. 239–50.

xxii. Sean J. Westwood, Justin Grimmer, Matthew Tyler, and Clayton Nall, “Current research overstates American support for political violence,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, Vol. 119, No. 12, March 22, 2022, e2116870119.

xxiii. States United Democracy Center, Americans’ Views on Political Violence—Key Findings & Recommendations, June 15, 2023, accessed October 25, 2023. Available at: https://statesuniteddemocracy.org/resources/americans-views-political-violence/

xxiv. Michael Coppedge, John Gerring, David Altman, Michael Bernhard, Steven Fish, Allen Hicken, Matthew Kroenig, Staffan I. Lindberg, Kelly McMann, Pamela Paxton, Holli A. Semetko, Svend-Erik Skaaning, Jeffrey Staton, and Jan Teorell, “Conceptualizing and Measuring Democracy: A New Approach,” Perspectives on Politics, Vol. 9, No. 2, 2011, pp. 247–67.

Appendix

The following survey findings are from the November 2022 VOTER Survey, which interviewed 6,000 Americans from November 15 to December 6, 2022.

1. Here are various types of political systems. For each one, would you say it is a very good, fairly good, fairly bad or very bad way of governing this country?

|

Having a strong leader who does not have to bother with Congress and elections. |

Having the army rule. |

Having a democratic political system. |

| Very Good |

Having a strong leader who does not have to bother with Congress and elections.

6% |

Having the army rule.

4% |

Having a democratic political system.

47% |

| Fairly Good |

Having a strong leader who does not have to bother with Congress and elections.

17% |

Having the army rule.

14% |

Having a democratic political system.

38% |

| Fairly Bad |

Having a strong leader who does not have to bother with Congress and elections.

21% |

Having the army rule.

19% |

Having a democratic political system.

10% |

| Very Bad |

Having a strong leader who does not have to bother with Congress and elections.

56% |

Having the army rule.

64% |

Having a democratic political system.

6% |

2. Please read the following statements and tell us which is closest to your view, even if none of them are exactly right.

| Democracy is preferable to any other kind of government. |

73% |

| In some circumstances, a non-democratic government can be preferable. |

15% |

| For someone like me, it doesn’t matter what kind of government we have. |

12% |

3. Please read the following statements and tell us which is closest to your view, even if none of them are exactly right.

| Since the President was elected to lead the country, he should not be bound by laws or court decisions that he thinks are wrong. |

11% |

| The President must always obey the laws and the courts, even if he thinks they are wrong. |

89% |

4. Please read the following statements and tell us which is closest to your view, even if none of them are exactly right.

| The news media should scrutinize the President and other politicians to ensure they are accountable to the American people. |

82% |

| The news media should allow the President and politicians to make decisions without being constantly monitored. |

18% |

5. Please read the following statements and tell us which is closest to your view, even if none of them are exactly right.

| Members of Congress should provide oversight of the President and executive branch, even if the President is in their same party. |

83% |

| Members of Congress should give the President freedom to make the decisions he feels are right for the country. |

17% |

For the following scenarios about unilateral executive action, one group of respondents was asked:

Please read the following scenarios. How appropriate would it be for a Democratic or Republican President to take action on their own, even if the Constitution does not give them the power to act without Congressional approval?

Another group of respondents was asked:

Please read the following scenarios. How appropriate would it be for President Biden to take action on his own, even if the Constitution does not give him the power to act without Congressional approval?

6. Scenario: The country is facing an immediate military threat.

|

President |

President Biden |

| Very Appropriate |

President

27% |

President Biden

25% |

| Somewhat Appropriate |

President

31% |

President Biden

27% |

| Somewhat Inappropriate |

President

13% |

President Biden

14% |

| Very Inappropriate |

President

11% |

President Biden

15% |

| Don’t Know |

President

18% |

President Biden

19% |

7. Scenario: A large majority of the American people believe that the President should act.

|

President |

President Biden |

| Very Appropriate |

President

15% |

President Biden

14% |

| Somewhat Appropriate |

President

28% |

President Biden

25% |

| Somewhat Inappropriate |

President

18% |

President Biden

16% |

| Very Inappropriate |

President

20% |

President Biden

25% |

| Don’t Know |

President

19% |

President Biden

21% |

8. Scenario: The President / President Biden knows it is the right thing to do for the American people.

|

President |

President Biden |

| Very Appropriate |

President

12% |

President Biden

12% |

| Somewhat Appropriate |

President

24% |

President Biden

19% |

| Somewhat Inappropriate |

President

20% |

President Biden

18% |

| Very Inappropriate |

President

25% |

President Biden

31% |

| Don’t Know |

President

19% |

President Biden

19% |

9. Scenario: The President has sought a compromise with Congress but the other party is playing partisan games.

|

President |

President Biden |

| Very Appropriate |

President

11% |

President Biden

13% |

| Somewhat Appropriate |

President

23% |

President Biden

21% |

| Somewhat Inappropriate |

President

20% |

President Biden

16% |

| Very Inappropriate |

President

24% |

President Biden

27% |

| Don’t Know |

President

23% |

President Biden

22% |

10. In some countries, military leaders have suspended elections, closed down the legislature, and temporarily taken charge of the government in order to address extreme corruption. What would

be your view if the military took these steps in the United States?

| Strongly Favor |

5% |

| Somewhat Favor |

10% |

| Somewhat Oppose |

11% |

| Strongly Oppose |

54% |

| Don’t Know |

19% |

11. When, if ever, is it OK for Democrats/Republicans/people to send threatening and intimidating messages to Republican/ Democrats/political leaders you don’t agree with?

|

Democrats |

Republicans |

People |

| Never |

Democrats

85% |

Republicans

82% |

People

88% |

| Occasionally |

Democrats

8% |

Republicans

11% |

People

9% |

| Frequently |

Democrats

4% |

Republicans

4% |

People

3% |

| Always |

Democrats

4% |

Republicans

4% |

People

1% |

12. When, if ever, is it OK for an ordinary Democrat/Republican/people in the public to harass an ordinary Republican/person you don’t agree with politically on the Internet, in a way that makes the target feel unsafe?

|

Democrats |

Republicans |

People |

| Never |

Democrats

87% |

Republicans

82% |

People

87% |

| Occasionally |

Democrats

7% |

Republicans

10% |

People

9% |

| Frequently |

Democrats

4% |

Republicans

4% |

People

2% |

| Always |

Democrats

3% |

Republicans

4% |

People

2% |

13. How much do you feel it is justified for Democrats/Republicans/people to use violence in advancing their political goals these days?

|

Democrats |

Republicans |

People |

| Not At All |

Democrats

84% |

Republicans

85% |

People

81% |

| A Little |

Democrats

6% |

Republicans

6% |

People

7% |

| A Moderate Amount |

Democrats

6% |

Republicans

6% |

People

8% |

| A Lot |

Democrats

3% |

Republicans

2% |

People

2% |

| A Great Deal |

Democrats

2% |

Republicans

1% |

People

2% |

14. How confident are you that votes in your community were counted as voters intended in the elections this November?

| Very Confident |

50% |

| Somewhat Confident |

32% |

| Not Too Confident |

11% |

| Not At All Confident |

8% |

15. How confident are you that votes across the United States were counted as voters intended in the elections this November?

| Very Confident |

38% |

| Somewhat Confident |

31% |

| Not Too Confident |

19% |

| Not At All Confident |

12% |

16. Which comes closer to your own views, even if neither is exactly right?

| There has been permanent harm done to the United States as a result of the election process this year. |

36% |

| There has been no permanent harm done to the United States as a result of the election process this year. |

64% |

17. Would you say that Joe Biden legitimately won the 2020 election, or not?

| Biden legitimately won the election. |

69% |

| Biden did NOT legitimately win the election. |

31% |

18. Overall, do you approve or disapprove of the actions taken by the people who forced their way into the U.S. Capitol on January 6th, 2021?

| Strongly Approve |

4% |

| Somewhat Approve |

7% |

| Somewhat Disapprove |

13% |

| Strongly Disapprove |

66% |

| Don’t Know |

10% |

19. Thinking about the people who forced their way into the U.S. Capitol on January 6th, 2021, would you describe their actions as…

|

Insurrection |

Patriotism |

Trying to Overthrow the U.S. Government |

Trying to Overturn the Election and Keep Donald Trump in Power |

Defending Freedom |

A Protest that Went Too Far |

| Yes |

Insurrection

60% |

Patriotism

25% |

Trying to Overthrow the U.S. Government

59% |

Trying to Overturn the Election and Keep Donald Trump in Power

68% |

Defending Freedom

26% |

A Protest that Went Too Far